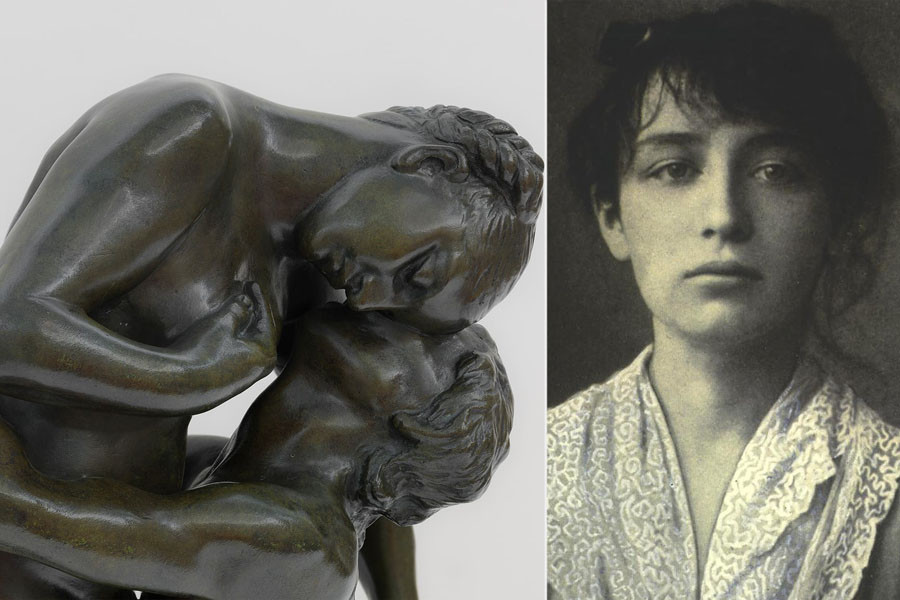

Female sculptor buried in the mass grave of the mental hospital: Camille Claudel

Behind every successful man there is a great woman. Camille Claudel was the great woman behind the famous Auguste Rodin, the founder of modern sculpture. For many years, Camille Claudel's biography was overshadowed by that of Auguste Rodin, and she was better known as her muse and lover.

Camille Claudel's full name was Camille-Rosalie Claudel and she was born in Villeneuve-sur-Fère, France, in 1864. Camille Claudel's biography often describes her as the assistant, lover, and muse of the French sculptor Auguste Rodin, or as the sister of the French poet Paul Claudel. However, she was much more than that. Claudel was also a sculptor, heavily inspired by Greco-Roman mythology and the works of Donatello and Cellini.

Despite the gender restrictions and prejudices imposed on her by 19th century society, Claudel nevertheless managed to become an artist.

Childhood and Early Education Years

Camille Claudel was the first child of a Catholic farming family of high social status. Claudel's brother, Paul Claudel, was born when she was four years old. Together they grew up in many different places, including Claudel's favorite Villeneuve-sur-Fère. She enjoyed the natural scenery of the countryside and this inspired her to start working with clay at the age of 12.

Her early work was admired by Alfred Boucher, who advised her parents to invest in their skills.

In 1881, Claudel moved to Paris, where she enrolled at the Colarossi Academy, now called the Grande Chaumière. Being admitted to Colarossi was a great achievement, as very few arts institutions accept female students. Claudel's admission to art school gave her the confidence to rent a studio space in 1882 with three female sculptors, including Jessie Lipscomb, Amy Page, and Emily Fawcett.

Realizing her talents as a child, Alfred Boucher became her mentor. Their relationship was always professional, but Boucher's respect and admiration for Claudel can be clearly seen in his 1882 sculpture, Camille Claudel lisant.

While women in sculptures from this period were typically depicted as sensual and erotic, Boucher instead depicts Claudel fully clothed with a book in hand, with a thoughtful gaze.

Assistant and Muse

Unfortunately, Boucher had to leave Claudel when he won the Grand Prix du Salon and moved to Italy. Boucher appointed Auguste Rodin as advisor to the group of young female students. Rodin, 43, was already an acclaimed sculptor at the time, and Claudel quickly became one of his best students.

This relationship soon developed further and Claudel became Rodin's lover and muse. Claudel began working as an assistant in Rodin's studio in 1883.

Camille Claudel and Rodin

The relationship between the two sculptors was a concern for Claudel's family, and while her father still supported her financially, the rest of her family treated her like an outcast and had to leave her family home. Claudel became one of Rodin's most trusted aides and worked on some of Rodin's most famous sculptures, including The Kiss (1882) and The Gates of Hell (1880-1890). Rodin openly praised Claudel's work and described her as an original creative genius.

Rodin admired Claudel not only for her art but also for her beauty, and both sculptors modeled several portraits of each other. Rodin's deep feelings for Claudel were recorded in “Eternal Springtime” (1884), “I Am Beautiful” (1885), “Portrait of Camille Claudel with a Bonnet” (1886), and “Mask of Camille Caudel” (circa 1895).

While their romantic relationship was also flourishing, Rodin was already in a serious relationship with Rose Beuret and had refused to end his relationship with Beuret. Claudel's jealousy of the relationship between Rodin and Beuret made her very uncomfortable and soon turned into paranoia and anger.

During her time as Rodin's assistant, Claudel constantly worked to improve her artistic skills. It even became a great inspiration for Rodin's art style. In 1886, Camille Claudel won a prestigious Salon Award for her sculpture Sakuntala. Critics praised the work's sensitivity and psychological impact on the human figure.

Camille Claudel's work began to change in 1892, nearly a decade after their relationship began, when her relationship with Rodin finally ended.

After the separation, Claudel no longer had access to the equipment Rodin could use in her studio, and her new work was smaller and showed feelings of sadness and despair. While Rodin offered to support Claudel financially, the betrayal she felt resulted in her refusing to receive any help from Rodin.

Despite her grief and loss of support, she continued to create and gave her best after the relationship ended. Claudel's new work draws from everyday experience and draws inspiration from Art Nouveau and Japanese prints.

Claudel also began experimenting with different materials and her work became even more unique.

Late Period

Living and working alone in her studio since 1899, Claudel began to experience serious financial difficulties. Records show that Rodin sought commissions for Claudel and paid her rent in 1904. In 1905, however, Claudel's sanity began to deteriorate, and Claudel became more reclusive. In 1912, Claudel destroyed much of her work in her studio out of frustration and anger. In 1913, her father, who had always supported Claudel's choices, passed away.

Claudel's family took the opportunity to be diagnosed with paranoia and schizophrenia, and Claudel was admitted to a mental institution. After her acceptance, the rest of her studio was destroyed.

Unfortunately, Claudel had spent 30 years in a mental institution and had few visits, including with her former artist friend Jessie Lipscomb and her brother Paul Claudel.

Rodin tried to help Claudel, but failed, and her fans and patrons openly criticized her family's unfair decision. Camille Claudel died alone in 1943 at the age of 78. Her family never claimed her body and she was buried in the mass grave of the mental hospital.