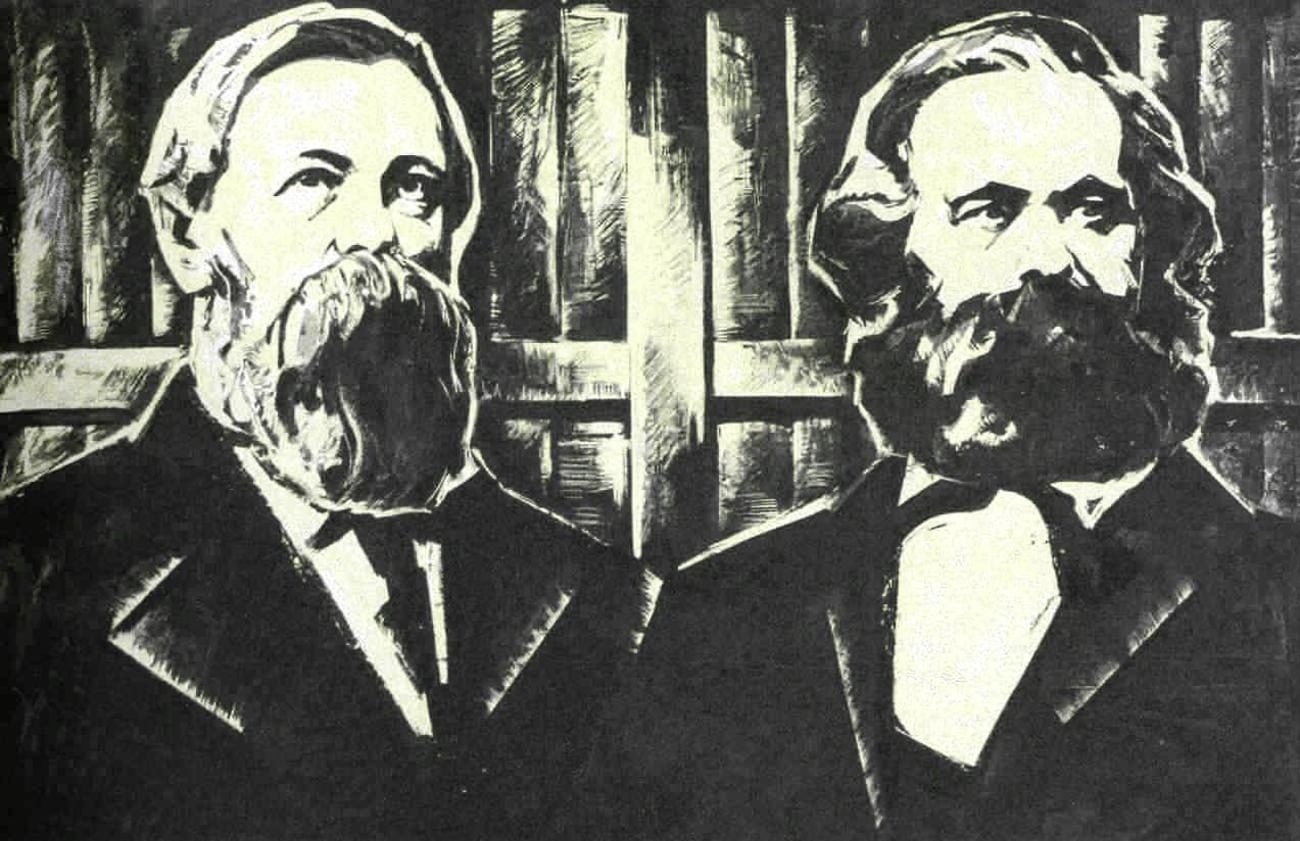

Das friendship: Marx & Engels; An amazing friendship story

“A specter is haunting Europe; The specter of communism…” Since the day they signed the Communist Manifesto, they started to be remembered together with this sentence.

In the poster tradition that started with the Soviets, the hierarchy did not change, it was even reinforced. Indeed, by describing himself as a "second fiddle", Engels gave firsthand approval to his subordinate position.

They met when they were just in their twenties. In Paris, in late 1843. Before Karl gives up, he finds Frederic cool and light. The next year's meeting takes place in warmer weather, and the glasses are like a memory of a friendship of forty years to come. When they met in Brussels the following year, Marx was expelled from France as well. By hosting him in England for six weeks, Engels helps him get to know the reality of the working class. They try to organize in Brussels when the steps of the uprising that will shake Europe are heard. In February 1848, when the rebellion broke out in France and spread to the continent, they returned to their homeland in Prussia and published a daily newspaper there. In June 1849, the military coup parted ways with the comrades. Marx was stripped of his citizenship and deported, while Engels joined the armed resistance fighters in the south, became an aide to the rebel commander, and left the region via Switzerland when there was no hope of victory.

While working at his father's weaving factory in Manchester, Engels corresponded with his comrade in London. This is a serious, disciplined, intellectual activity that continues every day, with the exception of 17 years of separation. These letters, if not all, have survived to the present day.

During this time, Engels wrote books and wrote articles on behalf of Marx for some publications. On the other hand, he informs his comrade, who is more interested in philosophy, on the functioning of capitalism, the situation of the working class, and its revolutionary potential. It was Engels himself who brought Marx to a revolutionary line, put the laws of political economy on his agenda, and made him a Marxist. Marx admitted this in a letter he wrote to himself: “You know, I follow you in everything, I always follow in your footsteps…”

The Second Violin still claims otherwise. Even though he actually wrote the Communist Manifesto, even though Marx went through it later, he says in the preface he wrote to the new edition of the book even after his partner's death: "Although the Manifesto is the joint work of both of us, I must state that the main idea that forms the core of the text belongs to Marx." What he said on another occasion is more modest and striking: “Many of the fundamental and leading ideas are the product of Marx's effort. What I contributed, Marx could very well have accomplished without me. But I could never have done what Marx did. Marx was passing us all, seeing farther, wider, and faster than all of us. Marx was a genius; we were only talents. That is why the theory is rightly called by the name of Marx.”

Das Capital. That's all genius. Marx spent almost two decades trying to write it down. He works at night in his wooden chair in his narrow room, crammed with books until the morning, and spends his days researching in the reading room at the British Museum. This slow pace of labor is no longer sustainable, except when he lays on the sofa and rests his head by reading a novel.

As a matter of fact, he was not recruited due to inflammation in his lungs due to excessive smoking and alcohol consumption in his youth. Now his liver is also devastated. Marx's troubles are innumerable; severe headaches and joint pains, eye inflammation, gallbladder problems, blood boil on his skin, and hemorrhoids, which he says as if it were not enough, "It affects me even more than the French Revolution." He suffers from insomnia and is dragged into depression because of the diseases he reproaches as "the misery of existence". He writes to a friend: “During this period, I already had one foot in the grave. So I had to use every working moment to finish my work for which I sacrificed health, happiness, and family.”

As he himself admits, his rigorous exaggeration, his obsession with accessing all sources, and his extreme perfectionism are eroding his strength day by day due to the prolonged hustle and bustle of reading and writing. When the material misery and the painful losses in the family are added to all these, the material misery that he has lived in places to leave his coat and watch to the moneylender, Marx's life turns into torture. Capital, aside from its content, is one of the most painful books of mankind in terms of its spelling and adventure.

At all stages, Marx sent texts to Engels, asking for opinions and criticism. His friend speaks bitterly and brings heavy criticism. For example, in some episodes, he says that "the traces of a boil are seen".

Engels encourages and provokes his friend to end this business as soon as possible. Mark is grateful. “Dear Fred,” the letters begin, “I hope you enjoy these four jerseys. The satisfaction you have shown me so far means more to me than anything the rest of the world can say.” Or “If this was possible, I owe it only to you! If it were not for your dedication to me, it would have been impossible for me to do the work required by the three volumes. I embrace you with gratitude!”

However, it only finishes the first volume. September 14, 1867. Neither sees nor utters a word. Engels sent 9 articles to different newspapers in order to break the silent plot and promote the book, 7 of which were published. Asked Marx, "Should I attack the book from a bourgeois point of view to get things right?" even in the offer. He also says: “…booksellers should not see our game openly.” These cunnings don't work either. Only 1000 copies of the printed book are sold in 4 years. With the bitter taste of tobacco, Marx will admit: “My books didn't even pay for the cigarettes I smoked while writing them.”

Since the day they met, Marx and his family have been living under the patronage of Engels. In fact, Engels is not very comfortable, judging by the letters he wrote in response to the warnings from his mother to prevent him from giving his money to Marx. Yet he continues to allocate a third of his family money, £50 a year, to his comrade. – He has other exile friends that he helps regularly. In Marx's letters during this period, phrases such as the following are frequently encountered: "I received the £15 you sent, thank you very much, my dear, virtuous friend..."

In 1869, Engels increased the amount he sent to Marx when he sold his partnership in the factory and had the money to live in prosperity for a lifetime. £350 per year and meet all urgent needs. (Approximately $52,500 in today's money.) According to the findings of some biographers, despite all the generosity of Engels, Marx and his aristocratic wife, whom he boasted as "the Baroness of Westphalia", would never see him as their equal.

Engels' heartfelt adventures are also noteworthy in this context. Although he has a very well-adjusted stance on homosexuality and prostitution, there is no doubt that he is a womanizer. He has not hidden his fondness for having fun with women since his youth. As a bourgeois, who does not believe in marriage, and since "conservatism", he has had relations with many women.

Engels was a very methodical man, sharply concentrating on what interests him and taking punctual notes. He had a radical temperament from the day he supported Greek independence against the Turks in his youth. He had refined tastes as a person who had dealt with poetry at an early age and had never broken his ties with literature, music, and art. There were also upper-middle-class habits such as fencing and drinking parties. These festivities attended by socialist intellectuals were also fox-hunting parties. Champagne was drunk until the morning and enjoyed the fun.

Engels had an extraordinary talent in linguistics. It is said that he knows about twenty European languages, especially Greek and Latin. He even studied Arabic and Persian for a few weeks. While writing Capital, Marx decided to learn Russian in order to reach the necessary information, and within six months he could read and understand fluently. The phrase “Foreign language is a weapon in the struggle for life”, which he often repeats, also reflects his own approach.

Engels was a gentleman, and spoke kindly to his opponents, while Marx was more inclined to speak his mind. While Marx's style was heavy and complex, Engels's was simpler and clearer. Another thing in common was that they were both citizens of the world.

Engels, who survived for 12 more years after his friend, also has Marx's daughter Eleanor on his 70th birthday, and in an article, he wrote to a Socialist newspaper, he writes that Engels is younger than he looks and has not aged at all in the last 20 years.

In 1895, Engels joined the caravan of death due to throat cancer. At his funeral, which was attended by Communist party leaders from different parts of Europe, his ashes were scattered in the sea by Eleanor Marx, 6 miles offshore, as per his will.

He leaves his $5 million fortune to Marx' two remaining daughters. In 1897, Eleanor kills herself with cyanide when she learns that her common-law husband embezzled this fortune and married another woman. The last child, Laura, is poisoned by her son-in-law, whom Marx advises to "take care of my daughter, so they don't suffer what we suffer". He himself will commit suicide with the same poison and write the following on his suicide note:

"Long Live Communism!"

Marx and Engels. They broke ground and left. Let Engels have the last word:

“The other world belongs to the poor anyway; sooner or later this world too will be theirs!..”

Hopefully!