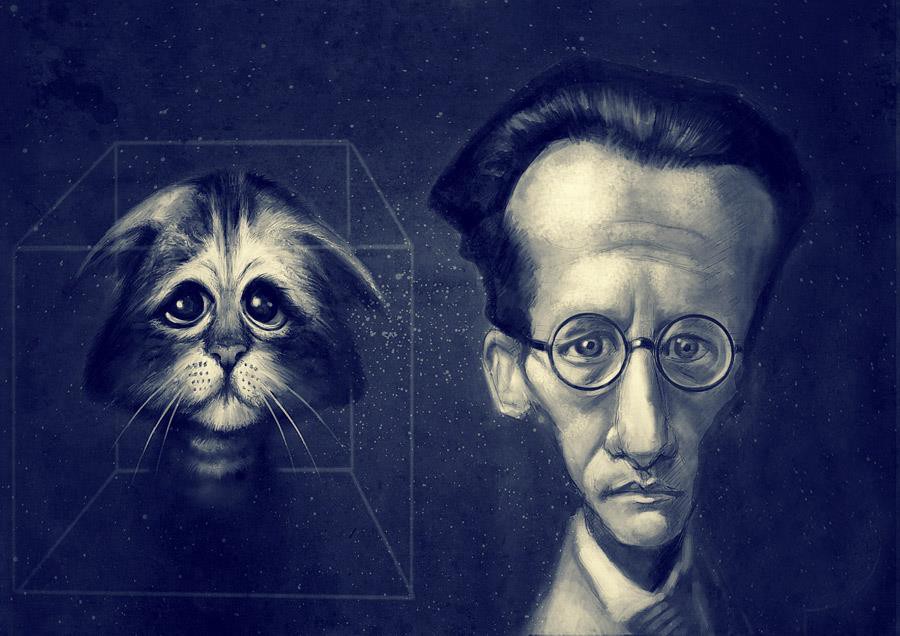

He became the world's most popular physicist with his cat dead or alive thought experiment: Erwin Schrödinger (1887 - 1961)

Schrödinger's cat is a much-debated thought experiment about quantum physics put forward by the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger. Let's get to know our physicist, who became popular with this thought experiment:

He was born on August 12, 1887, in the Erdberg district of Vienna, the only child of Rudolf and Georgine Emilia Brenda Schrödinger. Being the son of a wealthy industrialist, Schrödinger, who grew up taking private lessons at home, later entered the University of Vienna and became a successful student. He had even completed his doctorate at the age of 23.

He served as an artillery officer in the First World War. He was a professor at the University of Stuttgart, Germany. Schrödinger tried to express the behavior of the electron with a mathematical formula. He was honored with the 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work. He returned to his country after Hitler came to power the year he was a professor of theoretical physics at the University of Berlin. In 1938 he moved to England and later to Ireland and became a professor in Dublin.

The giant Schrödinger crater on the invisible side of the Moon is named after this physicist. The International Institute for Mathematical Physics, founded in Vienna in 1993, was named after Erwin Schrödinger. Schrödinger's picture was printed on the 1000 Schilling banknotes in circulation in Austria between 1983-1997. At the age of 69, longing for his homeland, Schrödinger returned to Vienna. He continued to work on unified field theory and general relativity. He described his worldview in his last book, My World View, published in 1961.

Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger, known for expressing the behavior of electrons, which are parts of the atom, with mathematical formulas and establishing wave mechanics, died on January 4, 1961, due to tuberculosis.

In an article he published in 1935, he explained the thought experiment called Schrödinger's cat. In the experiment, a healthy cat is placed in an empty air-permeable box. It is assumed that there is a poisonous gas in the can. The mechanism controlling the release of this gas from the bottle is also controlled by a radioactive particle with a decay half-life of one hour. In this case, due to the nature of the radioactive particle, we can only express the behavior in terms of quantum mechanics. In addition, since the behavior of the cat depends on this particle, we need to explain the cat's state with quantum mechanics. Schrödinger's claim is this: At the end of an hour, the probability of this cat being alive and dead is equal. The wave function decayed and the cat died or did not decay. It is not a sharp-edged function in the form of a cat alive. In this experiment, Erwin Schrödinger carries the physics problem of the microscopic world to the macroscopic world, arguing that the wave function does not offer only two options for the cat's condition and that it is not possible to know whether the cat is dead or alive without opening the lid of the box.

Erwin Schrödinger actually put forward the measurement hypothesis, which is a natural consequence of the wave function put forward by this experiment. If the wave function is correct, the cat must be dead and alive at the same time. This, of course, brought along new physics and philosophy problems.

Towards the end of January 1926, Schrödinger published his article "Quantization as an Eigenvalue Problem", which also included that famous equation. The Schrödinger equation designed a model whose electrons predicted the continuous motion of matter waves inside and outside the atom. By adding the classical expression of kinetic energy (energy of motion) to the classical expression of potential energy (positional energy), he reproduced them admirably as a mathematical function called the Hamilton operator. Schrödinger showed how the operator transforms the function by applying the Hamilton operator to the entity called the wave function in his famous equation today. According to the atomic model that he tried to clarify according to quantum theory, the position of the electron on the orbital was more like an energy wave surrounding the atomic nucleus, rather than being fuzzy and unknowable. A wave function expresses how a particle and its charge are distributed in space. According to Schrödinger, this was supposed to produce a standing wave, and so the electron did not need to emit light as long as it remained in such an orbital, although it did not represent an oscillating electric charge. Any number satisfying the equation indicated the corresponding energy level, and each psi function represented a steady state in that energy state. Thus, this view of Schrödinger did not violate the conditions imposed by Maxwell's equations. Over time, physicists called this view of Schrodinger's wave mechanics.

The Schrödinger equation is an intermediary wave function that allows us to reach the result in the analysis of a quantum system. Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger was the first to discover the equation that expresses the variation of quantum wave systems depending on space and time. Therefore, after this date, the Schrödinger equation remained with its name. After the publication of "quantum hypotheses" by Max Planck, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, in 1900, the new idea that emerged in 1924, the de Broglie hypothesis, and the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, which was put forward in 1927, led to the emergence of new theories in the scientific community. With these advances, Max Planck's quantum assumptions and Schrödinger's wave mechanics and theories were combined to reveal the theory of quantum mechanics.