Who are the female mathematicians who changed the world?

Throughout history, very few of the works of women have been accepted, their successes have been ignored, and their names have been forgotten in the books.

However, many women have accomplished successful studies in mathematics and have continued their studies successfully despite the pressure on them.

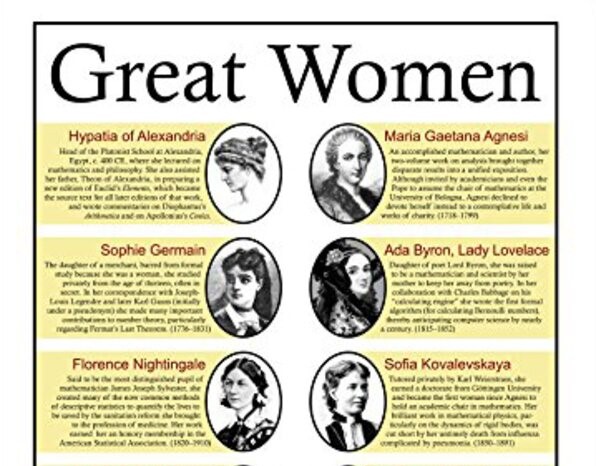

1. Hypatia (370 – 415)

Hypatia was the first female mathematician to make significant contributions to the development of mathematics. Her father Theon, an astronomer and mathematician, noticed the talents and eagerness to learn of Hypatia, and raised her daughter in this regard, despite the opposition of many people around her.

Over time, Hypatia has grown into a respected and charismatic teacher who is loved by all her students. She edited books on geometry, algebra, and astronomy, and was engaged in astrology and the construction of machines that showed the motion of the planets.

With the death of Hypatia, who was killed by torture at the age of 45 because she interpreted her ideas as paganism, female mathematicians entered a period of retreat and the existence of another woman, Maria Agnesi, who was known as a mathematician in history, was only brought to the agenda during the Renaissance.

2. Sofia Kovalevskaya (1850 – 1891)

Kovalevskaya made important contributions to the theory of differential equations and was the first woman to receive a doctorate in mathematics.

This woman, who was in love with mathematics, had to get married at the age of 18 after completing her basic education with private lessons. Because in Russia at the time, it was considered forbidden for a woman to live separately without the permission of her father or husband. When she went to study mathematics in Heidelberg in 1869, she had to face the fact that women could not attend university. Nevertheless, she convinced the university officials to continue her classes illegally.

In 1871 he moved to Berlin to study with the mathematician Karl Weierstrass, but he was not allowed to attend university classes again. In the autumn of 1874, Kovalevskaya completed 3 works; each considered a Ph.D. subject by Weierstrass. The studies were related to partial differential equations, integral, and Saturn's ring. In 1874 Kovalevskaya received her doctorate from the University of Göttingen, but this again did not secure her an academic position.

Despite the endless obstacles brought by her gender and political identity, Sofia, who was the first woman to teach at a university chair in Europe, died at the age of 41 as a result of the progress of her illness that started with a cold.

3. Emmy Amalie Noether (1882 – 1935)

Noether was described by Albert Einstein as "an important and creative mathematical genius despite the late start of women's higher education."

He is famous for her contributions to abstract algebra. He is generally known for proving the relationship between symmetries in physics and the closure theorem, known in some places as Noether's Theorem. Noether's work on the theory of variables helped formulate many of the general concepts of Einstein's theory of relativity.

Noether, who had to do most of her broadcasts under a pseudonym, is little known today. However, Russian topologist Pavel Alexandrov described Emmy Noether as the best female mathematician ever.

4- Sophie Germain (1776 – 1831)

Deciding to become a mathematician, influenced by the book she read about Archimedes' death as a child, Sophie developed herself by secretly reading the works of Newton and Euler, although her family found this interest inappropriate, and eventually, with her family's permission, by collecting lecture notes from the Ecole Polytechnique, where women were forbidden to attend. She continued her education on her own.

Reading Joseph-Louis Lagrange's lecture notes on analysis, Sophie submitted a work under the pseudonym M. Le Blanc, and the originality and content of the paper prompted Lagrange to seek its author.

Sophie Germain's contributions to the solution of the famous Fermat Theorem in mathematics are considered very important by the scientific community. These studies shed light on the developments in number theory over the next 100 years. Germain has participated in many math competitions and written articles, but never achieved the degrees she deserved.

5- Maria Agnesi (1718 – 1799)

Agnesi is famous for her work in differential calculus. At the age of 7, she learned Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, and by the age of 9, she published a speech on women's rights to higher education. Apart from her peers, she studied the mathematical work of Descartes, Newton, Leibniz, and Euler. She also educated the youth of her family and taught at scientific and mathematical meetings organized by her father. Maria, who wrote a 2-volume mathematics book on integral calculations, infinite series, and differential equations, was selected as a member of the Bologna Academy of Science as a result of the interest in this book. Although she was later invited to teach in Bologna, she turned down this call and gave up doing scientific work after her father's death. Agnesi devoted the remaining 47 years of her life to sick and dying women.

6-Caroline Herschel (1750 – 1848)

Caroline Herschel was the first woman to discover a comet and be officially recognized as a scholar, and the first woman to receive honorary membership from the Royal Society. Herschel made important contributions to the field of astronomy. This woman, who was 1 29 cm tall due to an illness she had as a child, preferred to cover up her physical defect with her mind. In 1783, Caroline discovered many nebula and star clusters, including the open star cluster known today as NGC2360.

7- Ada Lovelace (1815-1852)

Ada Gordon (Countess of Lovelace, due to her husband's title) is considered one of the first pioneers of computer history. The reason why it went down in the history of mathematics and computers was an algorithm that Babbage wrote for her primitive computer called the "Analytical Machine". The Analytical Machine was never built, but it inspired the development of the first modern computer in the 1940s.

Ada Lovelace translated Italian mathematician Louis Menabrea's review of the Analytical Machine published in French in 1842 for a British scientific journal and added her own notes to this translation and published it in 1843. In these notes, she detailed how to calculate Bernoulli numbers with Babbage's machine. This method has been accepted by historians as the world's first computer program. Thus, Ada Lovelace became the "first programmer".

8- Joan Clarke (1917 – 1996)

Joan Clarke's name has been overshadowed by a man's name, like many women working in different fields. This person is Alan Turing.

When Turing was commissioned by the government to work on a machine called “Enigma” used by the Nazis during World War II, which was used to encrypt and send war-related information, Joan Clarke, who was part of her team, graduated from Cambridge in 1939, although she graduated in two fields. cited its success as a code-breaker, as women were not admitted to “full membership” in academia. Although she rose to the position of department chief, she never received an equal salary with a man and became one of the forgotten geniuses.

9. Florence Nightingale (1820 – 1910)

Florence Nightingale is one of the first names that come to mind when it comes to nursing. However, she has a not-so-known side, which is that she is a good mathematician and statistician.

Educated by her father, Florence grew up as an enlightened woman who was knowledgeable in Greek, Latin, French, German, Italian, history, philosophy, and mathematics. She wanted to shift her education to mathematics, but this request was not welcomed by her family. She started to deal with health problems over time, but she was more in the organization part of the job. She started doing statistical analyzes of health problems in hospitals. Her statistical analysis also included the health problems of post-war soldiers. Her mastery in the use of statistical techniques led to Florence Nightingale being elected as the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society in 1858.