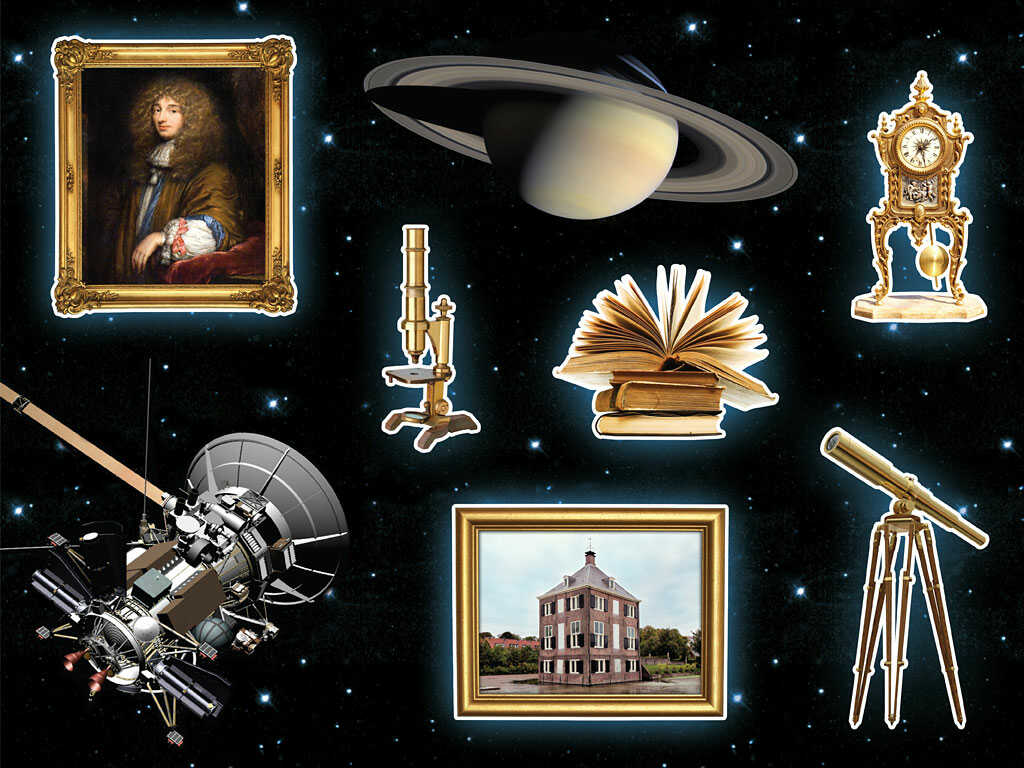

The genius who discovered Saturn: who is Christiaan Huygens?

Christiaan Huygens has done extensive work as a mathematician, astronomer, physicist, and horologist. He made important contributions to light wave theory and probability theory in particular.

Among his important works are the discovery of the true structure of Saturn and its moon Titan, the invention of the pendulum clock, and other research on the workings of time.

Huygens' father Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687), who was born in the Netherlands on April 14, 1629, was a diplomat and poet and belonged to a distinguished family. Huygens had mechanical drawing and math skills that were evident even at an early age. His early efforts in geometry influenced his father's friend, Descartes (French Mathematician and Philosopher, 1596-1650). In 1645 Huygens entered Leiden University, where he studied mathematics and law. He visited Paris for the first time in 1655.

While in Paris, he met Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), with whom he had previously corresponded on mathematical problems. In 1666 Huygens became one of the founding members of the French Academy of Sciences. The Academy awarded him more pensions than any other member and gave him an apartment in its building. Except for occasional visits to the Netherlands, he lived in Paris from 1666-1681. There he met the German mathematician and philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) and became friends.

Christiaan Huygens, (14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution. In physics, Huygens made seminal contributions to optics and mechanics, while as an astronomer he studied the rings of Saturn and discovered its largest moon, Titan. As an engineer and inventor, he improved the design of telescopes and invented the pendulum clock, the most accurate timekeeper for almost 300 years. A talented mathematician and physicist, his works contain the first idealization of a physical problem by a set of mathematical parameters, and the first mathematical and mechanistic explanation of an unobservable physical phenomenon.

Sometimes he had trouble keeping up with the new work of Leibniz and others. As a mathematician, however, Huygens had great talent as well as a first-degree genius. Sir Isaac Newton (1643-1727) admired him for his love of ancient synthetic methods. Huygens' health deteriorated in 1670 due to recurrent illnesses. He suffered so severely that he gave up hope for his own life for a while. The last five years of Huygens' life were marked by his melancholy mood due to his illness. He made the final corrections to his will in March 1695. He died on 8 July 1695.

Although he rejected some of Descartes' views on philosophy, he knew that his work on mechanics was crucial to science. In his primary work, he confirmed Descartes' Cartesian principles, which included the identity of space and body. This confirmation had a significant impact on the mathematical interpretation of the theories of light and gravity developed by Huygens.

Huygens learned probabilistic studies from the correspondence between Pascal and Fermat. On his return to the Netherlands, he wrote a small book called De Ratiociniis in his first published work, Ludo Aleae, on the calculus of probabilities. In addition to this work, his work De Circuli Magnitudine Inventa, which he wrote in 1654, is also important in the field of mathematics.

In March 1655, he discovered Saturn's moon Titan, and distinguished the planet's stellar components. Moreover, he made a great scientific breakthrough with the discovery of the true shape of Saturn's rings in 1659. He achieved this discovery with the telescope he developed using a new lens grinding and polishing method. He described the Orion Nebula in 1656. As an astronomer, he had a great interest in the accurate measurement of time.

Christiaan Huygens' Studies on Clocks

This interest, as he explains in his book Horologium (1658), led him to invent a clock controlled by the movement of a pendulum in 1656. In fact, there are debates about the priority of the invention of the pendulum clock. This invention has been attributed to Galileo by some authorities and to Huygens by others. But Huygens was given priority because he had solved the fundamental problem of a pendulum's period.

Huygens' interest in using a freely suspended pendulum to regulate clocks began in December 1656. Huygens' design, Horologium (1658), which he patented the following year, became widely popular. These efforts led to many pendulum clocks being built and even adapted to existing clock towers such as Scheveningen and Utrecht. The highlight of Huygens' years in Paris was the publication in 1673 of his book Horologium oscillatorium sive de motu pendularium (Clock Oscillator).

He also wrote a published treatise on the possibility of extraterrestrials, called Cosmotheoros. This work was published posthumously. In Huygens's discussion of the nature of light concerning reflection and refraction in his Treatise on Light (1690), there were mechanical explanations far superior to Newton's.

It took more than a century for researchers to trust the Dutch scientist's wave theory. For almost all of the 18th century, his work on both dynamics and light was overshadowed by Newton. His theory on gravity was never taken seriously and is only of historical interest today. Still, his work on rotating bodies and his contributions to the theory of light are of lasting importance. These results, which were forgotten until the beginning of the 19th century, appear as the most original contributions to science today. All of these keep the name of Christiaan Huygens alive.