From Astronomer to Science Fiction Writer: Who is Fred Hoyle?

Hoyle's Cambridge years (1945-1973) went down in scientific history thanks to his astonishingly original ideas covering a wide range of topics.

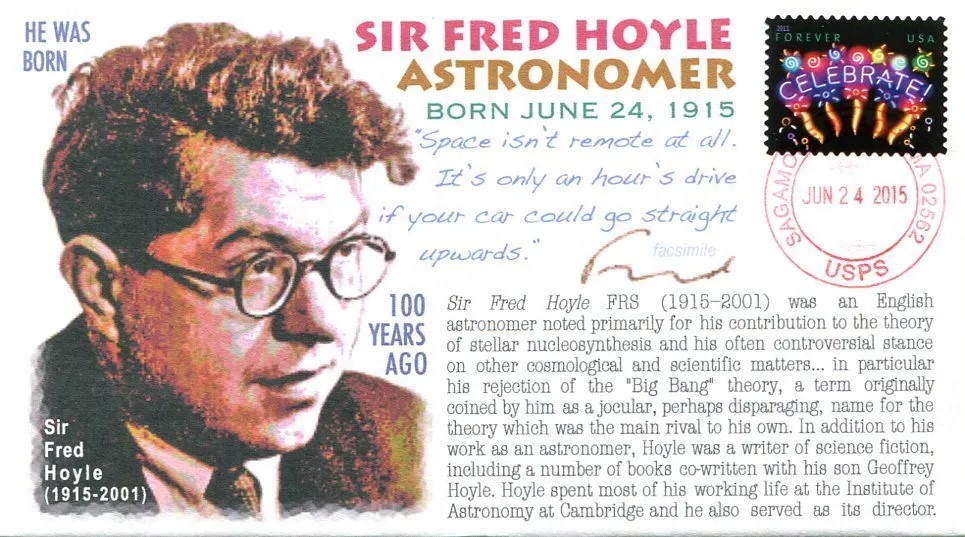

Fred Hoyle was a British astronomer born in 1915 who formulated the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and co-authored the famous B2FH paper. He also has controversial stances on some scientific issues. In particular, his most well-known thesis is his rejection of the "Big Bang" theory in favor of the "steady state model" and his introduction of panspermia as the origin of life on Earth.

He has also written science fiction novels, short stories, and radio plays. He co-wrote twelve books with his son Geoffrey Hoyle. He spent most of his working life at the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge, where he served as director for six years.

Sir Fred Hoyle (24 June 1915 – 20 August 2001) was an English astronomer who formulated the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and was one of the authors of the influential B2FH paper. He also held controversial stances on other scientific matters—in particular his rejection of the "Big Bang" theory (a term coined by him on BBC Radio) in favor of the "steady-state model", and his promotion of panspermia as the origin of life on Earth. He spent most of his working life at the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge and served as its director for six years.

Hoyle was born near Bingley in Gilstead, West Riding of Yorkshire, England. His father, Ben Hoyle, a violinist and wool merchant in Bradford, fought as a machine gunner in the First World War. His mother, Mabel Pickard, studied at the Royal College of Music in London and later worked as a film pianist. Hoyle was educated at Bingley Grammar School and studied mathematics at Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

In late 1940 Hoyle left Cambridge to conduct radar research (e.g. determining the altitude of incoming aircraft) for the British Admiralty. He was also assigned to take countermeasures against radar-guided weapons in the River Plate. Britain's radar project employed more personnel than the infamous Manhattan Project, and it likely served as the inspiration for the major British project in Hoyle's novel The Black Cloud. He engaged in deep discussions on cosmology with two colleagues involved in this work, Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold. The Radar Institute also funded several trips to North America, where he had the opportunity to visit astronomers. On another trip to the USA, he learned about supernovae at Caltech and Mount Palomar, and about the nuclear physics of plutonium in Canada.

He noticed some similarities between the two and began studying supernova nucleosynthesis. Finally, in 1954, his visionary and groundbreaking article appeared. He also founded a group in Cambridge investigating stellar nucleosynthesis in ordinary stars, but he was not expecting the lack of carbon production in stars in existing models. He realized that one of the existing processes could be made a billion times more efficient if the carbon-12 nucleus had a resonance at 7.7 MeV. On another trip, he visited the nuclear physics group at Caltech, where he worked on leave for several months and also conducted research on his own theory.

After the war, he returned to Cambridge University as a lecturer. Hoyle's Cambridge years (1945-1973) went down in scientific history thanks to his astonishingly original ideas covering a wide range of topics. In 1958 Hoyle was appointed Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at the University of Cambridge. In 1967 he became the founding director of the Institute for Theoretical Astronomy (later renamed the Cambridge Institute of Astronomy), and his innovative leadership made the institution renowned in the field of astrophysics. In 1971 he was invited to deliver the MacMillan Memorial Lecture at the Institute of Engineers and Shipwrights in Scotland. He was awarded the title of knighthood in 1972. In 1972, Plumian resigned as professor and in 1973 as director of the institute, a move that cut him off from his connections and regular salary.

After leaving Cambridge, he wrote many popular science and science fiction books and gave lectures around the world. The biggest source of motivation was to provide a means of financial support. He was still a member of the joint policy committee during the planning phase (since 1967) for the 150-inch Anglo-Australian Telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales. In 1973 he became chairman of the Anglo-Australian Telescope board, and in 1974 he was appointed by Prince Charles of Wales to preside over the opening of the facility.

Hoyle was at the center of two famous debates over the Nobel Prize in Physics. First, the 1974 prize was given to Antony Hewish for his leading role in the discovery of pulsars. “Yes, unlike Hewish, Jocelyn Bell was an intellectual researcher,” Hoyle told a reporter in Montreal. "In addition, Bell was Hewish's supervisor and therefore should have been included in the award," he said. This statement attracted attention in the international media. Concerned about being misunderstood, Hoyle subsequently wrote a letter of explanation to The Times.

The second controversy broke out in the 1983 award. William Alfred Fowler was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for "Theoretical and experimental investigations of nuclear reactions important in the formation of chemical elements in the universe." Hoyle became the inventor of the theory of nucleosynthesis in stars with two research papers published shortly after World War II. Rumors thus spread that Hoyle had been excluded by the committee because he had voiced objections to the 1974 Nobel Prize in physics. British scientist Harry Kroto stated that the Nobel Prize is not only given for a study but is also about giving a reputation to science and scientists. John Maddox, the well-known editor of Nature magazine, also stated that it was "shameful" that Fowler was awarded the Nobel Prize and Hoyle was not.

In his first novel, The Dark Cloud, he talked about intelligent life forms that take the form of interstellar gas clouds. In fact, these creatures were quite surprised when they learned that life could also form on planets. The novel A for Andromeda, which he wrote with John Elliot, was adapted into a seven-episode television series on the BBC in 1961. Additionally, his play "Rockets in the Big Bear" was staged in a professional production at the Mermaid Theater in 1962.