The British hated by the Turks: Who is General Harington?

General Harington was the Commander-in-Chief of the Occupation Armies of Istanbul between 1920-1922. During this duty, he tortured the Turks greatly. Harrington's actions have a large share in the Turks' great hatred of the English.

Born in Chichester in 1872, Charles Harington graduated from the British Royal Military Academy in 1892 and was appointed to the Royal Liverpool Regiment with the rank of First Lieutenant the same year. Harington, who was later assigned to South Africa, participated in the Second Boer War in 1899. Promoted to Captain in 1900, Harington was given various assignments in England. Harington, who was among the officers sent to the Western Front to aid France in the First World War, commanded British troops in various conflicts and was promoted to general by taking ranks. Harington, who was then appointed as the Deputy Chief of the General Staff, had a hard time due to the anti-British actions that took place in Ireland and India during this duty. During the investigation of the Jallianwala Bagh (Amritsar) massacre, which was carried out in India on April 13, 1919, on the orders of British General Reginald Dyer, criticism was leveled against Harington that he undermined the accusations. The British government considered it appropriate to appoint Harington, who was worn out by criticism in this process, to a critical mission in Istanbul, which was under the occupation of the Allied Powers.

General Sir Charles Harington Harington, GCB, GBE, DSO (31 May 1872 – 22 October 1940) was a British Army officer most noted for his service during the First World War and the Chanak Crisis. During his 46 years in the army, Harington served in the Second Boer War, held various staff positions during the First World War, served as Deputy Chief of the Imperial General Staff between 1918 and 1920, commanded the occupation forces in the Black Sea, and Turkey, and ultimately became Governor of Gibraltar in 1933.

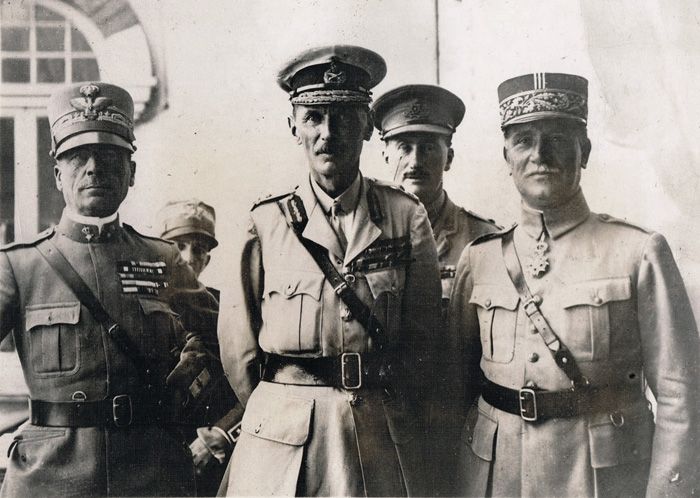

The British, French, and Italian High Commissioners and Generals, who had actually occupied Istanbul since 13 November 1918, established an occupation administration by reconciliation. However, there was a serious rivalry between the Commander of the Black Sea Allied Army, British General Milne, and the Commander of the Eastern Allied Army, French General Franchet d'Espèrey, over the command of Istanbul. General Milne was de facto acting as the commander-in-chief in Istanbul, while d'Espère was objecting to this. Meanwhile, while the Entente Powers were officially occupying Istanbul on March 16, 1920, the Turkish Grand National Assembly was opened in Ankara, and the Entente Powers were accelerating their attempts to implement the Treaty of Sèvres, which they had imposed on the government of Damat Ferid Pasha. In this process, the French drew d'Espèrey to the center; The British, on the other hand, wanted to alleviate the command crisis by appointing Harington to replace Milne in October 1920.

The issue gained a new dimension when the Italians, who verbally declared that they would accept the high command of the British, appointed General Ernesto Monbelli and the French appointed General Charpy to replace d'Espèrey. While Monbelli abstained on the issue of commander-in-chief, Charpy did not want to leave the dominance in Istanbul to the British. So much so that after the First İnönü War, Charpy rejected Harington's offer to send French soldiers along with the British, who were worried about the actions of the Kuva-yı Milliye against Izmit. Harington, who had to fortify in Izmit by getting reinforcements from the Greeks, made demands for the commander to gather under his own responsibility in Istanbul, on the grounds that he was in danger, and tried to increase his influence on the capital.

Considering the danger Harington pointed out, the British, French, and Italian governments; On May 13, 1921, declared their neutrality in the Turkish-Greek War in order to prevent the actions of the Turkish Grand National Assembly, which reached an agreement with the Soviet-Russian and increased its authority in Anatolia as a result of the İnönü Wars. Within the scope of this decision, it was reported that the immediate surroundings of the Istanbul and Çanakkale Straits were designated as neutral zones. The neutral zone that the three great Entente Powers had determined in order to secure their interests in Turkey, especially in Istanbul and the Straits region, was actually within the jurisdiction of Harington.

Although a security shield was created with the neutral zone, Harington attached great importance to maintaining order and security in Istanbul. In this context, Harington, who made the Allied police force functional, limited the field of activity of the Ottoman police. The Allied passport office, which, together with the Allied police, allowed entry to and exit from Istanbul by land and sea, also increased its effectiveness. Aircraft entry into the Straits area was also restricted by the proclamations issued by the High Commissioners and Harington. It was announced that those who acted in the opposite direction would be tried in the Allied military courts.

The Allied passport office, which prevented Turks from returning to the capital for ordinary reasons, easily granted visas to Entente citizens, Armenians, Greeks, and White Russians to enter the city. Since the said immigrants were granted visas without the necessary infrastructure and preparations being made, the social fabric of Istanbul was seriously damaged. Over time, the sheltering of the immigrants, the provision of their food, and their living in a healthy environment caused serious problems for the existence of both the people of Istanbul and the Allied forces. The emergence of some infectious diseases, especially typhoid fever, in the refugee camps left Harington, who was responsible for the said migrations, in a difficult situation. In a telegram on the matter, his gaffe that "40,000 prostitutes" were roaming the streets, referring to the White Russians in Istanbul, showed the psychology of Harington.

Harington, who made an effort to increase his influence on the Istanbul government together with the allied forces, was also trying to provide a meeting ground with Mustafa Kemal Pasha. In the middle of 1921, Harington gave the task of liaising with Mustafa Kemal Pasha to the former Major Henry, who was planning to cross to Ankara via İnebolu in order to engage in commercial activities. Mustafa Kemal Pasha assigned Refet Pasha to learn the intention of Henry, who could not go to Ankara because the roads have deteriorated. Refet Pasha, who contacted Henry, learned of Harington's desire to meet with Mustafa Kemal Pasha. Although Henry and Refet Pasha agreed to hold the said meeting in İnebolu, Harington claimed that the proposal for the meeting first came from Ankara. In this period, the British High Commissioner in Istanbul was trying to establish contact with Mustafa Kemal Pasha by including the unofficial representative of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey in Istanbul and the Chief of the Red Crescent, Hamit Bey, but he also emphasized that the meeting proposal should come from Ankara first. Mustafa Kemal Pasha, on the other hand, explained that the offer came first from the British and stated that he would only accept an official meeting with Harington, otherwise he would appoint a representative to negotiate. The intention of the British was to gain psychological superiority at the table by claiming that the offer to negotiate came first from Mustafa Kemal Pasha. However, sensing this, Mustafa Kemal Pasha never made any concessions and closed the doors of negotiations. Thereupon, Harington conveyed that his request to meet was accepted by his government and that they could meet on a British warship, but Mustafa Kemal Pasha, who made the national cause a matter of honor, rejected this offer without hesitation.

Unable to provide a basis for negotiation with Mustafa Kemal Pasha, the British, together with their allies, tried to establish a defense line around Maltepe-Çubuklu against the Turkish Grand National Assembly. The defense line planned to be established under the command of Harington gained even more importance after the Battle of Sakarya. Because, as the Turkish Grand National Assembly succeeded in Anatolia, a large-scale uprising was organized in Istanbul, the ammunition kept under surveillance in the warehouses would be smuggled, Turkish propaganda was made among the Indian-origin soldiers stationed in Turkey, and Harington and assassinations against collaborators such as Damat Ferid Pasha and Mustafa Sabri Efendi were carried out. information was received that it would be arranged. As a result of Harington's suggestions, arrests were made within the scope of the investigations carried out by the Tevfik Pasha government, but the allegations in question would come up frequently from now on.

After the Great Offensive, the British increased the level of alarm in Istanbul even more. The British forces took a defensive position on the Ezine-Bayramiç-Biga and Maltepe-Dudullu-Çubuklu lines upon the instruction of Harington, upon the possibility that the vanguard forces of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey would pass from Çanakkale to Thrace, and from the Asian side of Istanbul to the European side. Harington, who became more worried, was aware that the forces in the Straits region could not defend against the troops under the command of Mustafa Kemal Pasha. Moreover, it was understood that the support of the French and Italian forces could not be obtained at the point of defense of the Anatolian side. In the face of the advance of the TGNA pioneer forces, Harington transferred his forces on the Çatalca line to Izmit and Çanakkale. Harington, who made an effort to avoid conflict with the TBMM forces as much as possible and to withdraw the troops to Gallipoli, if deemed necessary, in line with the instruction he received from the center, sent Shuttleworth to Çanakkale on September 9, 1922. Meanwhile, Harington was planning to reinforce the troops in the Dardanelles with his forces in Malta, Egypt, and Gibraltar. But until this reinforcement was made, it could be too late, and the TGNA forces could enter the neutral zone.

As a matter of fact, Mustafa Kemal Pasha had instructed Yakup Şevki Pasha, who had returned from exile from Malta, to enter the neutral zone within the scope of the operation to encircle the Dardanelles. In a short time, the cavalry forces of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey advanced into the neutral zone, tore the thorns and wires, and lowered the British flag. The Turkish cavalry around Izmit likewise crossed the borders of the neutral zone. The British government secretly ordered Harington to stop the TGNA forces advancing in the neutral zone, but not to engage in combat unless fire was opened from the opposite side. Harington was in a difficult situation due to the almost impossible instruction from headquarters. It was a complete mystery how the TGNA forces could be stopped without opening fire. However, Mustafa Kemal Pasha was also giving secret instructions not to engage in conflict unless the British opened fire, considering the current military and economic resources and the political situation. In this process, which was described as the Çanakkale crisis, the British government was faced with important problems.

The British government, the problems experienced in Ireland and its colonies, the inadequacy of the forces in the Straits region, the possibility of a large-scale rebellion in Istanbul, the opposition of France and Italy to the war with the Turkish Grand National Assembly, the movement of the Turkish Grand National Assembly with the Soviet-Russia, economic stagnation and public opinion. He sent repeated instructions to Harington to avoid conflict with Parliament, taking into account factors such as his unwillingness to a new war. On the other hand, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey started a direct conflict with the British with the thoughts that its economic resources were starting to run out, even its reserve military forces were recruited, the lack of a strong navy, the possibility of the three allies establishing a common front in the Straits, and the desire to end the duality in the administration by taking over Istanbul as soon as possible. He didn't want to enter. However, Mustafa Kemal Pasha did not reflect his concerns on the field and ordered the Turkish troops to advance decisively in this region, ignoring Harington's messages through Hamit Bey that the neutral zone should not be violated.

The British government sent instructions to Harington to evacuate his troops from Istanbul and make Gallipoli his home base in case of the possibility of interruption of negotiations at the Lausanne Conference and the advance of Turkish forces towards the Straits. However, Harington reached an agreement with the French commander Charpy that the Straits should be defended as best he could. The Italians, who had few forces in the region, also supported the idea of defending the Straits politically. This compromise was an indication of the determination of the three allies, who could not establish a common front against the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Anatolia, to maintain control of the Straits.

With the understanding that a compromise would be reached at the Lausanne Conference, the tension in Istanbul decreased and a period of détente was entered. The fact that the football match held between Fenerbahçe and the British occupation forces on 29 June 1923 was described as the General Harington Cup was a sign of this softening. Finally, after the Treaty of Lausanne, the preparations for the ceremony to be carried out for the evacuation of Istanbul on October 2, 1923, were carried out on behalf of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, between Selahaddin Adil Pasha and Harington, representing the Entente States. passed into his administration.

Returning to his country, Harington took on various duties in the British army until 1933. Harington, who served as Governor of Gibraltar from 1933-38, died in 1940.