He is one of the most famous guerrilla leaders of the 19th century: Who is Giuseppe Garibaldi?

He is Italian, but he was not born in Italy. Napoleon was born in Corsica, not France, Von Moltke the Great was born in the duchy of Schwerin, not in Germany, Stalin was born in Georgia, not Russia, and Hitler was born in Austria, not Germany.

Garibaldi belonged to a poor family of sailors and fishermen. Although he was born on French soil, he always considered himself Italian.

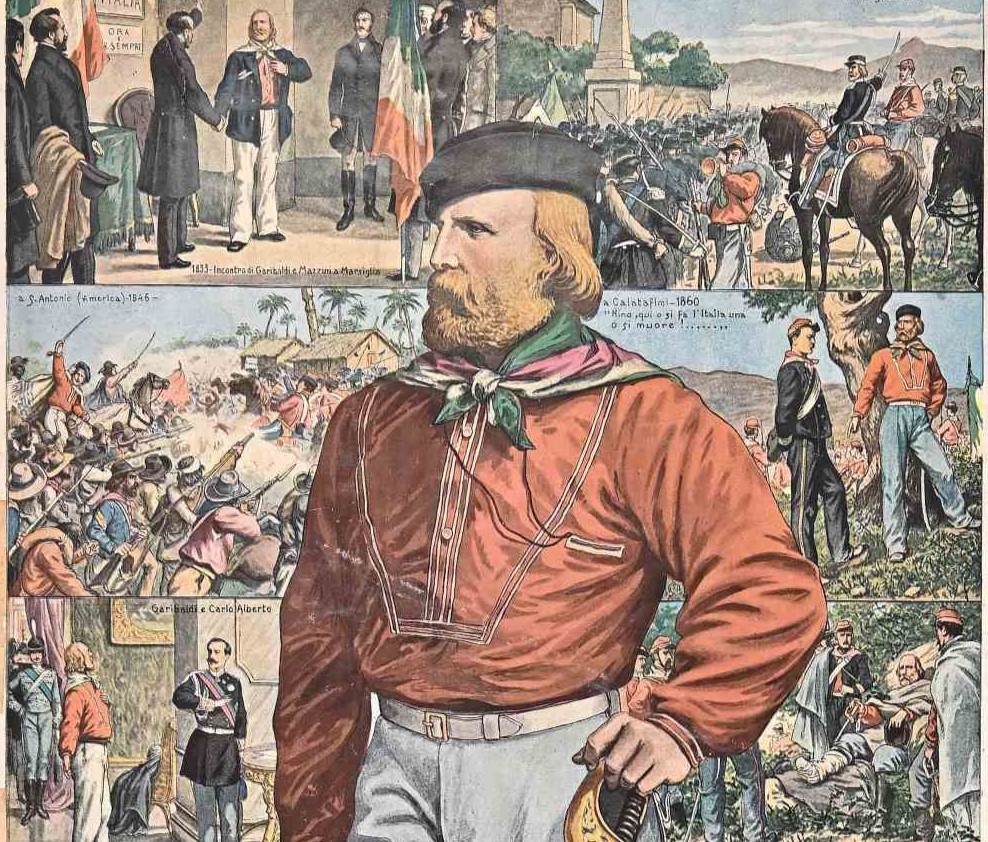

He started working as a shipboy when he was 16 years old. He traveled around the Mediterranean for 10 years. At the age of 26, he founded a secret society called "Young Italians". He participated in the 1834 rebellion under the leadership of Mazzini. But the rebellion was not successful; Mazzini was a master of pens, not guns. One of the reasons why the rebellion failed was that Mazzini, who would lead the rebellion, lost his way. As we know it, he failed to reach the rebels and got lost. When Garibaldi faced the death penalty, he had to take refuge in South America.

He entered the pasta business in South America; After all, he was Italian. But he went bankrupt. In 1837, he joined the army of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, which was struggling to separate from Brazil. He participated in the Uruguay War in 1842. He fought for six years on the side of the liberal government fighting against an Argentinian dictator and his local allies. Due to its maritime background, it sometimes fought at sea and sometimes on land.

Since the distances were long in South America, horses showed extraordinary endurance in riding. He never allowed his soldiers to mistreat the captives in the units he commanded, and if he was unable to detain the captives, he did not kill them but released them, even though he knew that they would report their location.

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi (July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, patriot, revolutionary and republican. He contributed to Italian unification and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. He is considered to be one of Italy's "fathers of the fatherland", along with Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy and Giuseppe Mazzini. Garibaldi is also known as the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in South America and Europe.

His most notable successes were the hit-and-run attacks he carried out at the head of the 800-man Italian legion. The uniform of this unit, which consisted of refugees like him in Uruguay, was a red shirt. This was because the red shirt did not show blood. In addition, these shirts and scarves would become the symbol of Garibaldi in the future.

By the way, Garibaldi was also a bit of a womanizer. He seduced Brazilian Anna Maria Riberio de Silva and married her. (The woman was actually married to someone else, but she divorced her husband for Garibaldi.) Garibaldi was 33 and Silva was 18. Garibaldi always called his wife Anita. Anna Maria traveled and participated in battles with Garibaldi for 10 years, and also gave birth to four children. Romantic relationships that challenged social conventions made Garibaldi famous as a rebel.

Garibaldi's achievements were conveyed to the public with enthusiastic expressions in the European newspapers of that period. The year was 1848, the month was June; When Garibaldi returned to Italy with his three legionnaires, he had already become a national hero. At that time, Italy was in a shared position between France and Austria. The Italians especially suffered greatly from the Austrians. When Garibaldi came to Italy, he wrote the following in his diary: “We had fought a glorious war to defend the oppressed in other countries. "Now is the time to take up arms for our only homeland."

Garibaldi joined the revolutionary committee in Milan. He and his 150 volunteers participated in conflicts in Austrian-occupied Lombardy. He wrote: "In the absence of an organized army, I hoped to draw my countrymen into a guerrilla war that would lead to the liberation of Italy." However the number of participants was not large. The Austrians had effectively intimidated the population with their brutal tactics. According to Garibaldi, when the Austrians were repelled from a village, they mercilessly set fire to all the houses in the surrounding area. They were bombing the village indiscriminately.

After three weeks of fighting, Garibaldi had to cross the Swiss border and take shelter here. Austria won this round. A year later, Garibaldi returned home with 1300 men from the Italian legion. He aimed to defend the newly declared Roman Republic against Austria, France, and Spain. Garibaldi hoped to wage a guerrilla war from his redoubts in the Apennine mountains. But he was ordered by Mazzini, the de facto leader of the Roman Republic, to mount a desperate conventional defense. Citizens were mobilized and barricades were erected. They initially stopped the attacks, but with the superiority of logistics and firepower, defeat was inevitable.

Garibaldi decided to leave Rome and continue the war. His call to volunteers would be developed and expressed by Churchill: “We will fight them in factories, fields, schools, mountains, barricades, everywhere, but we will never surrender. "Those who love their country and victory should follow me."

More than four thousand people heeded this call. Among them was his wife Anita, who was pregnant with her fifth child. They were followed by an army of Austrians, French, Spanish, and local traitors. During the desperate march that would last a month, many of Garibaldi's soldiers deserted, and the villagers did not participate in his war. After all, the Pope had described Garibaldi as the antichrist and the villagers were conservative people. Garibaldi wrote in his diary: “My fellow Italians behave timidly and like women.”

His wife caught malaria and died during this walk. This was a heavy blow for Garibaldi. However, Garibaldi's ability to avoid being caught during this walk, which was a precursor to Mao's "Long March", would add to his fame.

After the revolutions of 1848 ended, Garibaldi went into exile once again. During this exile, he lived in London, Peru, New York, and China. To make ends meet, he worked a variety of jobs, from making candles to captaining a cargo ship carrying bat feces. In 1856 he settled on the small island of Caprera, near Sardinia. The four-room stone mansion he built with his own hands, with a small inheritance from his brother, became a shelter that he would use until the end of his life. A lock he had cut from his wife's hair hung over his bed in an ivory frame. However, this did not prevent Garibaldi from "paying attention to women", in the words of one of the women he was in a relationship with. He married once again when he was 52 years old. The woman he married was 18 years old, like his first wife. But more interestingly, a man approached Garibaldi during the wedding and handed him a note. In the note, he wrote that the bride had spent the previous night with him and that she did not like her new husband. Garibaldi immediately asks the bride whether what is written in this note is true. When his wife confirmed this, he called her a “whore” and declared that she was not really his wife, and they never spoke again. Since he had not officially divorced his wife, he did not enter into another official marriage. Then he married, albeit unofficially, the woman who was his children's nanny. He also had three children from her. Of course, these are just known facts...

Garibaldi was like a lion in a cage during the years he spent in Caprera. As one of his girlfriends wrote, “He was impatiently waiting for the day when he would be summoned again by Risergimento.” That day came in 1858. He was put in charge of the irregular troops, that is, the guerrilla forces, by the cunning aristocrat Count Camillo di Cavour, who was the prime minister of Piedmont-Sardinia. As expected, the war broke out in 1859. Garibaldi, who was promoted to Major General in the Piedmontese army, was still wearing his old red shirt and red cloak. He set out once again to start a guerrilla war with 3000 young people, called the hunters of the Alps, who were inadequate in weapons but had high morale. He served in the wings of the army. (Note that in all conventional wars, guerrillas-partisans, etc. generally work either on the wings or as rearguards.) Garibaldi's goals were to wear out the Austrian army, cut off transportation routes by blowing up bridges, and burn warehouses. He took advantage of the mountainous terrain and won successive victories against the Austrians, who were superior to him, more crowded and equipped. They knew how to fight especially at night and made bayonet attacks. And in the end, Garibaldi's side won the war. The founding of Italy began.

Garibaldi played a more central role in the next phase of the Risorgimento Movement (meaning resurrection). This phase began with the uprising that broke out in Sicily against the king of Naples, who belonged to the Bourbon dynasty (French origin). Cavour took a wait-and-see attitude. If Garibaldi succeeded, he would support it; if it failed, he would reject it. On his own initiative, Garibaldi came to the aid of the Sicilians with 1100 volunteers. This group, consisting mostly of workers, students, and intellectuals living in Northern cities, was called "Thousands" or "red shirts". A historical commentator states that this group's belief in Garibaldi was "almost like a religion."

This small unit landed in the port of Marseille. Meanwhile, the Bourbon warships that had just left the harbor were a great opportunity for Garibaldi. Four days later they encountered Bourbon soldiers: 3000 Bourbon soldiers against 1000 Redshirts. Moreover, the weapons in the hands of Garibaldi's soldiers were old. Garibaldi told them to fire as little as possible and attack the hill mostly on the flanks and in a dispersed manner. This was something that would never happen in conventional warfare of that period. Since the enemy remained on a fixed front line, he was doomed to defeat. Garibaldi later wrote in his diary: This conflict had a tremendous and inestimable result in encouraging the people and demoralizing the enemy army. The Red Shirts, aided by local guerrilla gangs, the MAFIA, marched on Palermo. Approximately 20,000 soldiers guarded the city. While the soldiers were marching on Garibaldi, Garibaldi and his men headed towards the hills and mountains and carried out deceptive movements day and night. He never went into battle in the open field. Even Garibaldi's men could not make sense of this. One student wrote in his diary: What does it mean that we constantly revolve around Palermo like moths around a lamp? If Garibaldi had read this he would have just laughed.

The awaited moment came on the night of May 27, 1860. The enemy was caught unprepared in Palermo. During three days of intense street fighting (it was like a mini-Stalingrad), Bourbon cannons spewed death upon civilians. This brutality enraged the people rather than intimidating them. The people began to fight with Garibaldi's men to prevent the movement of the Bourbon infantry.

Garibaldi, who took Sicily, crossed the Strait of Messina and set foot on the Italian mainland. In Naples, he fought the largest conventional-scale war of his life with his 30 thousand men against the Bourbon force of 50 thousand people and won the war. Naturally, he was at the front. As he walked with his revolver in hand, cannonballs and shrapnel were flying around him, a war correspondent wrote.

He ruled Sicily and Naples for a while. Then he handed over these places to Victor Emmanuel, the first Italian King. In a characteristic manner, he rejected offers of rich rewards and retired to Caprera. Being such a selfless person was one of the secrets of his being respected by the public. A British naval officer who knew Garibaldi commented on him as follows: "The secret of the irresistible spell that enabled him to win all hearts lies in a simple fact: he is an honest man."

Thanks to his worldwide fame, Garibaldi was often invited to participate in other people's wars. He did not accept Abraham Lincoln's offer to join the American Civil War in 1861 because the North had not yet abolished slavery and his request to become commander of all Union armies was rejected by Lincoln.

Until 1870, he fought, was defeated, captured, and escaped many times against the Royal Italian Army, supported by Napoleon III and the French Imperial Army, and the military forces of the Pope. Finally, with the collapse of the Crown, the breaking of the influence of the Papacy, and the establishment of the Italian Republic, in 1870, Garibaldi put his genius at the service of republican France, which prepared the Paris Commune. He defeated the Prussian Royal forces with the Vosges army he led with his two sons.

In the general elections held in 1871, he was elected as a member of the French Parliament, representing 4 provinces within the borders of the Bordeaux region. But this time, the reactionaries, who were in the majority in Bordeaux, canceled Garibaldi's parliamentary membership on the grounds that he was not fully French. Garibaldi, who entered the Italian parliament as a Roman deputy in 1874, founded the "League of Democracy", which was the most important freedom and peace platform of the period and also turned into a political organization. Garibaldi, who retired to his own island of Caprera in Sardinia in 1880, wrote his "Memoirs" until his death.

Only one institution was disturbed by this most loved and respected historical face of Italy: the Vatican. I wonder why? Because Garibaldi was a secular republican revolutionary who wanted to put an end to the dominance of religion and church over the state and society.

He died in 1882 at the age of 74. British Historian A J P Taylor described him as the only figure in modern history who can be appreciated in every aspect. He was a pioneer of the 20th-century guerrillas who would gain worldwide fame. He was worthy of praise more than all the other guerrilla leaders because he never lost his humanity and self-control while fighting and never sought personal power and wealth.

Giuseppe Peppino Garibaldi is Italy's first universal and legendary hero and is also a historical figure that everyone somehow carves for themselves. Benito Mussolini, the father of fascism, considered himself the natural extension of Garibaldi, as he gave Italy its unity. Of course, Garibaldi is still almost a cult figure for the Italian right today. Can the 'other' Italy be left out of the leadership of the war of independence and unity, inspired by the French Revolution, and the 'red' shirted volunteer soldiers and revolutionaries who constitute the mobilization army known as the 'Thousands'? Moreover, Garibaldi, the commander of the "Red Shirts" army, was a social patriot who organized "Workers' Associations" in solidarity with his country all over the world, including Istanbul. For these reasons, he is accepted as the founder and symbol of the history of Italian social struggle by the entire Italian left, especially by Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937) and Palmiro Togliatti (1893-1964), leaders of the Italian communist and labor movement. The famous French historian Jules Michelet (1798-1874), who wrote one of the best-known works on the French Revolution, writes about Garibaldi: "I know only one hero in Europe, not two: Garibaldi, whose life is an epic."