He said that, "I do not follow romantics or idealists; nature is my only teacher": Who is Gustave Courbet?

A painter who slaps the pictures of the poor and working people in the face of the rich. Courbet describes figures from the working class who represent the lowest part of society, as plainly and unpretentious as possible, with all their ordinariness and reality without any hesitation.

Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet was born on June 10, 1819, in a town in the Jura region of Ornans, a place in eastern France near the Swiss border. Courbet's father was a wealthy landowner in Ornans, and his maternal grandfather was a successful winemaker in the Loue Valley and a Town Councilor in Ornans.

He comes from an environment and family that includes all class ideas, whether peasant, bourgeois, conservative, or progressive. This situation has been very effective in determining and developing the artist's preferences.

Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet (10 June 1819 – 31 December 1877) was a French painter who led the Realism movement in 19th-century French painting. Committed to painting only what he could see, he rejected academic convention and the Romanticism of the previous generation of visual artists. His independence set an example that was important to later artists, such as the Impressionists and the Cubists. Courbet occupies an important place in 19th-century French painting as an innovator and as an artist willing to make bold social statements through his work.

Courbet went to Paris to study law at his father's request in 1839 but decided to study painting. He took lessons from Carl von Steuben and Nicolas-Auguste Hesse. He attends private academies run by Charles Suisse and Père Lapin. With the encouragement of the painter François Bonvin, who would later become one of his closest friends, he tends to copy the paintings of famous artists in the Louvre Museum. In 1846-1847 he stays in the Netherlands and Belgium. He delves into the works of French, Spanish, and Flemish artists to create his own style.

Courbet's early works are dominated by self-portraits and romantic elements. One of these works, Self-Portrait with a Black Dog and a Pipe, was not exhibited by the Paris Salon but gradually became known thanks to the news about him. In later years, he was delighted when his Self-Portrait with a Black Dog was accepted by the Paris Salon. Although his work is exhibited in a way that he does not desire, his self-confidence increases as a start.

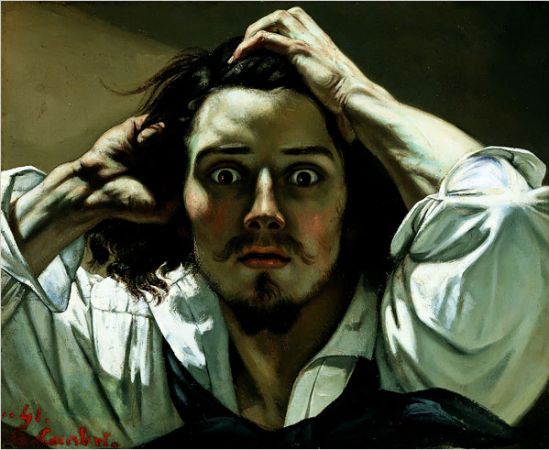

(Above picture) In his work, The Desperate Man, Courbert expresses his anger, especially against the romanticism movement, but while doing this, he cannot stop using the romantic lines of his period in his work. In this self-portrait, he is regarded by art critics as the pioneer of the realism movement, as he reflects reality as it is and portrays his despair with all clarity. When viewers look at the portrait, they get not only his desperation but also the idea of what kind of personality the charismatic Gustave Courbet is: Brave, radical, ambitious, and determined.

He portrayed himself as pulling out his hair in order to emphasize the emotions wanted to be expressed. The fact that the portrait is drawn from such a close-up gives us the feeling that we too cannot escape from that feeling of hopelessness. The fact that one of the wrists is light and the other is dark creates a contrast and symbolizes the artist's confusion of emotions. The brightness of the cheeks and lips is designed to attract the attention of the viewer.

Towards 1847, Courbet's political view of life and his understanding of painting began to change. At first, he adopted the peaceful understanding of the socialist philosopher Charles Fourier, while from 1847 he was influenced by the socialist thoughts of the anarchist thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

Stone Breakers and Funeral in Ornans are two important masterpieces of Courbet, which can be considered as turning points both for himself and for the history of art. Because these works are the first examples in terms of reaching wider layers of the people, conveying their lives, and most importantly leading the unknown and unlimited life of the proletariat (worker, working class).

Courbet describes these two figures, who are from the working class and represent the lowest part of society, as plainly and unpretentious as possible, with all their ordinariness and reality without any hesitation. This situation is like a slap to the bourgeoisie, which was presented to their liking at that time.

In 1855, Napoleon III organized the World's Fair in Paris to showcase the cultural, social, and industrial progress of France. In order to reveal the superiority of France in art, an exhibition featuring only works of art is also organized. While 35 paintings from Delacroix and 40 from Ingres were selected for the Universal Exhibition, Courbet's most mysterious and allegorical composition, The Painter's Workshop and Funeral in Ornans, which he completed in eight weeks, among the 11 accepted paintings, each figure has a different meaning. pictures are eliminated by the jury. He also exhibits 40 canvases across the exhibition hall in what he calls the Realism Pavilion, along with the one that was not accepted to protest. Prepares a statement stating and defending its purpose. This event, which was successful in the face of critics, said, “I do not follow romantics or idealists. Nature is my only teacher," and brings Courbet to the fore.

Prepares the Realist Manifesto for the exhibition catalog:

- Art cannot be taught! There are no art schools, there are artists.

- Imagination in art is about how to fully express what exists; otherwise, it is not inventing that object or creating that thing itself.

- The beauty created by nature is superior to the inventions of the artist.

- Beauty, like truth, is about the time one lives and the capacity of individuals to understand it.

- Realists (Realism): They want to put an end to artificiality not only in art but also in society and therefore they defend individual rights. Realistic artists have reflected the troubles, poverty, and all the realities of life in society as they are. Therefore, the artifacts have historical significance.

Courbet, who rejected the Legion d'Honneur with Honoré Daumier in 1870, wrote in a letter addressed to the French Minister of Fine Arts: "I could never, under any circumstances, accept this. On a day when treachery is multiplying everywhere and self-interest is so widespread, I cannot accept it at all… As an artist, it does not comfort me that the hand of the government is the one who bestowed this honor on me. I do not see the state as authoritative in matters of art.”

Courbet is appointed Minister of the Union of Arts of the Paris Commune, which was established in 1871 after the dethronement of Napoleon III and hence the collapse of the Second Empire. He participated in the revolutionary activities of the commune during these years when he was tasked with reopening the museums and organizing the Salon Exhibitions. He decides to protect important monuments such as the Sevres Porcelain Workshop and Fontainebleau Palace against the German bombardment but resigns from his post by not participating in the extreme behavior of the commune.

He was tried in a military court established in September 1871 and sentenced to 6 months in prison, after the commune ended due to his involvement in the destruction of the Vendome Monument erected in memory of Napoleon Bonaparte's great army. After he is released from prison, he is kept under duress, and all his property is confiscated. Courbet, unable to withstand these pressures, fled to Switzerland in 1873.

Courbet died on December 31, 1877, in Switzerland, where he took refuge, away from his homeland, due to liver disease.