German novelist who won the 1972 Nobel Prize in Literature: Who is Heinrich Böll?

His stories about the war and Germany in its post-war ruins, with the experiences of ordinary people, made him famous in a short time.

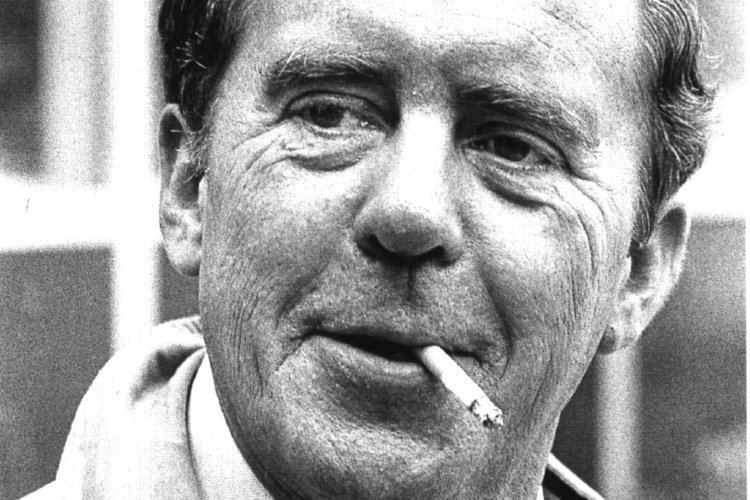

German novelist and storyteller. He received the 1972 Nobel Prize in Literature. He was born on December 21, 1917, in Cologne, Germany. His father was a carpenter. His childhood and youth passed in a Catholic environment. After graduating from high school in 1937, he first worked for a bookstore and then enrolled in university. His education was interrupted when he was drafted into the army at the start of the war. He served on various fronts during World War II. He married his literature teacher, Annemarie Cech, in 1942. He was captured by the Allies in 1945 and remained in American and British prison camps. When the war ended, he returned to Cologne and started his university education again, but he did not continue this and worked in temporary jobs he found.

Heinrich Theodor Böll (21 December 1917 – 16 July 1985) was a German writer. Considered one of Germany's foremost post-World War II writers, Böll is a recipient of the Georg Büchner Prize (1967) and the Nobel Prize for Literature (1972)

His first short stories were published in 1947. His stories about the war and Germany in its post-war ruins, with the experiences of ordinary people, made him famous in a short time. In 1949, his first novel, Der Zug war punktlich (It Was the Time of the Train), was published. He has been a freelance writer since 1951. In 1967 he received the Büchner Prize, one of the leading literary prizes in the Federal Republic of Germany. He was president of the Federal German Pen Club in 1970-1971 and of the International Pen Club in 1971-1974. He pioneered the syndication of German writers in 1969. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1972.

Taking the American short story understanding as an example, especially Hemingway, Böll became the most widely read and discussed writer in the Federal Republic of Germany and the most well-known abroad in a short time with his realistic and clear narration.

It was The Hour of the Train, published in 1949, is the story of a young soldier returning to the front. During the journey that lasts for days until his destination, the young soldier cannot understand his friends and feels lonely and abandoned. While waiting to die as heroes, their friends spend time playing cards and telling jokes. After spending a few hours with a young Polish girl he met in a city close to the front, the young soldier realizes that despite all the horrors of the war, there is still room for tender feelings and consolation among people.

In his novel Und sagte kein einziges (And He Said Nothing), his novel about marriage, he tells the story of a husband and wife living apart from each other due to the difficulties of living in Germany amidst the ruins of the war. The novel reflects an example of many marriages that were tried to be carried out in those days in despair and desperation.

His later novels also reflect his search for a new style and subject matter. In the novel Haus ohne Hüter (Fatherless Houses), published in 1954, he tells the desperation of people from two different social segments in the example of two families whose men died in war and whose children grew up without a father. In the hopeless environment created by the war, widows can neither live nor die, and children cannot reach puberty.

In his novel Billard um halbzehn (Billiards at Nine and a Half), published in 1959, he deals with Nazi Germany by processing the memories of three generations of a wealthy German architect family with the flashback technique.

As a humorist and satirist besides his novels, Heinrich Böll focused on the frivolous aspects of social reality in his country and also translated the works of writers such as Bernard Shaw, O Henry, and J. D. Salinger into German.

In recent years, he has become a much-discussed author in his country with the political views he defended in his essays, articles, and statements. He defended the rights of the individual, and the democratic state of law against the authoritarian development tendencies in the structure of the state, and criticized the rearmament efforts after World War II. Although he is not attached to any political ideology, he claimed that he was an addicted writer based on a moralistic understanding.