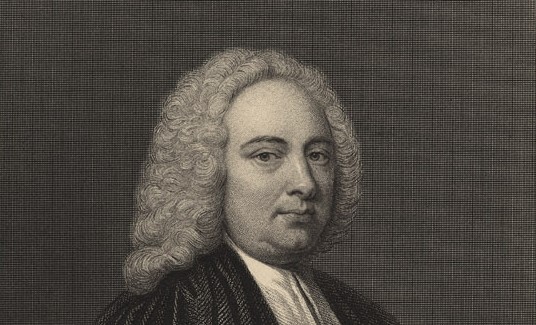

20 years as an astronomer at the British court: Who is James Bradley?

After Halley's death in 1742, Bradley became a court astronomer at his request, and he carried out this task with great success for 20 years.

(1693-1762) English astronomer. He discovered the deviance between the real and visible places of the celestial bodies, and sensitively measured astronomical magnitudes such as the tilt of the earth's axis and the diameters of the planets. He was born in Sherbourne, Gloucestershire, in March 1693. He belonged to a well-established and noble family. Since his father, William Bradley, had a limited income, he pursued his education with the financial assistance of his uncle, James Pound, who was a pastor in Wanstead. His uncle, who is also one of the leading amateur astronomers in England, is the person who instilled Bradley's love of astronomy. After graduating from Bradley Northleach High School, he entered Balliol College at Oxford University in 1711. He received his bachelor's degree in 1714 and master's degrees in 1717. In 1742, Bradley was awarded the title of honorary doctor.

James Bradley, who became pastor in 1719, was ordained to Bridstow Church. However, taking advantage of the fact that his religious duties did not take much time, he was able to visit his uncle in Wanstead frequently to participate in astronomy observations. With the encouragement of Halley, one of the greatest astronomers of the time, introduced by his uncle, he made observations of Mars and some nebulae in 1716. A year later, when Halley asked the Royal Society to take into account Bradley's industriousness and talent and stated that much was expected of him in astronomy, Bradley was elected a Fellow in 1718, and three years later he was appointed professor at Oxford, whereupon he quit his religious duties and devoted his life to astronomy. devoted.

After Halley's death in 1742, Bradley became a court astronomer at his request and carried out this task for 20 years with great success. After becoming a court astronomer, he corrected his mistakes by reviewing the instruments at the Greenwich Observatory. Between 1742 and 1750 he completely renovated the observatory. From 1750 until his death, his intense observations of more than 60,000 stars ensured Greenwich Observatory's punctuality to this day. In the last years of his life, his health deteriorated due to overwork, and in 1761 he was completely unable to work. He died in Chalford, Gloucestershire, on July 13, 1762, as a result of an abdominal infection. Besides being a member of the Bradley Royal Academy, he was also a member of the French, Berlin, Bologna, and St Petersburg scientific academies.

James Bradley's most famous discovery was that due to the finite speed of light, the divergence of light from the stars resulted in the fact that the actual and apparent locations of the star were different from each other. This discovery is one of the best examples of Bradley's diligence, attention, perceptiveness, and ability to turn what seemed like a failure into success. Although Robert Hooke suggested in 1669 that the stars would shift sideways due to the Earth's rotation around the Sun and that the distance to the stars could be calculated by measuring these shifts, neither Hooke nor Samuel Molyneux(1689-1728), who used a brand new telescope in 1725, had a problem. they had results. Molyneux, a wealthy amateur astronomer, invited Bradley to his home so they could continue the measurements together. Observations made first on the star Gamma Draconis (Draconis) revealed the existence of a very small shift. Continuing observations have revealed that both this and other stars show a regular shift each year, and this shift is not due to parallax or refraction of light in the atmosphere. After Molyneux gave up on these observations, James Bradley continued his observations by having a larger telescope built in 1727. He tried many hypotheses to explain his observations, eventually finding that the event occurred as a result of the Earth's rotation around the Sun with the finite speed of light. Bradley made a careful calculation to prove the validity of this invention. He presented the result of his work to the Royal Society in 1729. Thus, he provided the first observational proof of the Copernican theory, which assumed that the parallax phenomenon in the stars was much less than had been thought and that the Earth revolved around the Sun.

In 1727, James Bradley observed a small, recurrent annual change in the tilt angles of fixed stars. Nor could this change be explained by the deviation of light. Therefore, he continued to observe other fixed stars until 1723. He speculated that the reason for this change was the gravitational effect of the Moon on the ground, and the change in angle between the Moon's orbital plane and the Earth's orbital plane caused a change in the tilt of the Earth's axis. Since this movement was repeated every 19 years, the stars had to return to their former places at the end of this period. Bradley continued these observations for 19 years and found that his prediction was correct. In 1748 he submitted a paper describing this phenomenon, which he called nutation, to the Royal Society. His article included observations of many stars on oscillation, declination, and rotational angles between 1727 and 1747, as well as information about the refraction of light in the atmosphere, and corrections to be made as this refraction changes with pressure or heat.

James Bradley also made careful observations on planets in the Solar system. Together with his uncle in 1719, with the help of his observations of Mars, he sensitively measured the value of the Sun's parallax (the difference in angle resulting from observing a point from two different locations). He detected the orbits of many comets. He calculated the latitudes of Lisbon and New York using the difference between the eclipse times of one of Jupiter's bright moons. In 1730, he observed the ring system around Saturn. He made important strides in measuring the diameters of the planets Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the ring system around Saturn. Measuring these diameters has been a difficult task 150 years later, even for astronomers with much better instruments.

One of James Bradley's important duties as a court astronomer was to measure time accurately. To this end, he sent a one-second-accurate clock in London to Jamaica, where it was observed that the clock was delayed by 1 minute and 58 seconds a day due to the bulge of the equator relative to the poles. As Bradley found the same result from Newton's theory of gravity, he then prepared a chart showing the length of pendulums that completed their oscillation in 1 second for all latitudes. Another achievement is the sensitive determination of the latitude of Greenwich. The value he found was 1.3 seconds more than the true value and was more precise than the measurements of the two astronomers working after him.

James Bradley was an original thinker, an adept and careful observer, and an astronomer with practical discoveries. He carefully studied the measurement errors in his instruments and worked hard to correct these errors and fine-tune the instruments.