The latest and highest point in the evolution of classical music: Who is Johannes Brahms?

He remained a staunch German patriot with his life, views, and expectations. It can be said that he hates everything English and French.

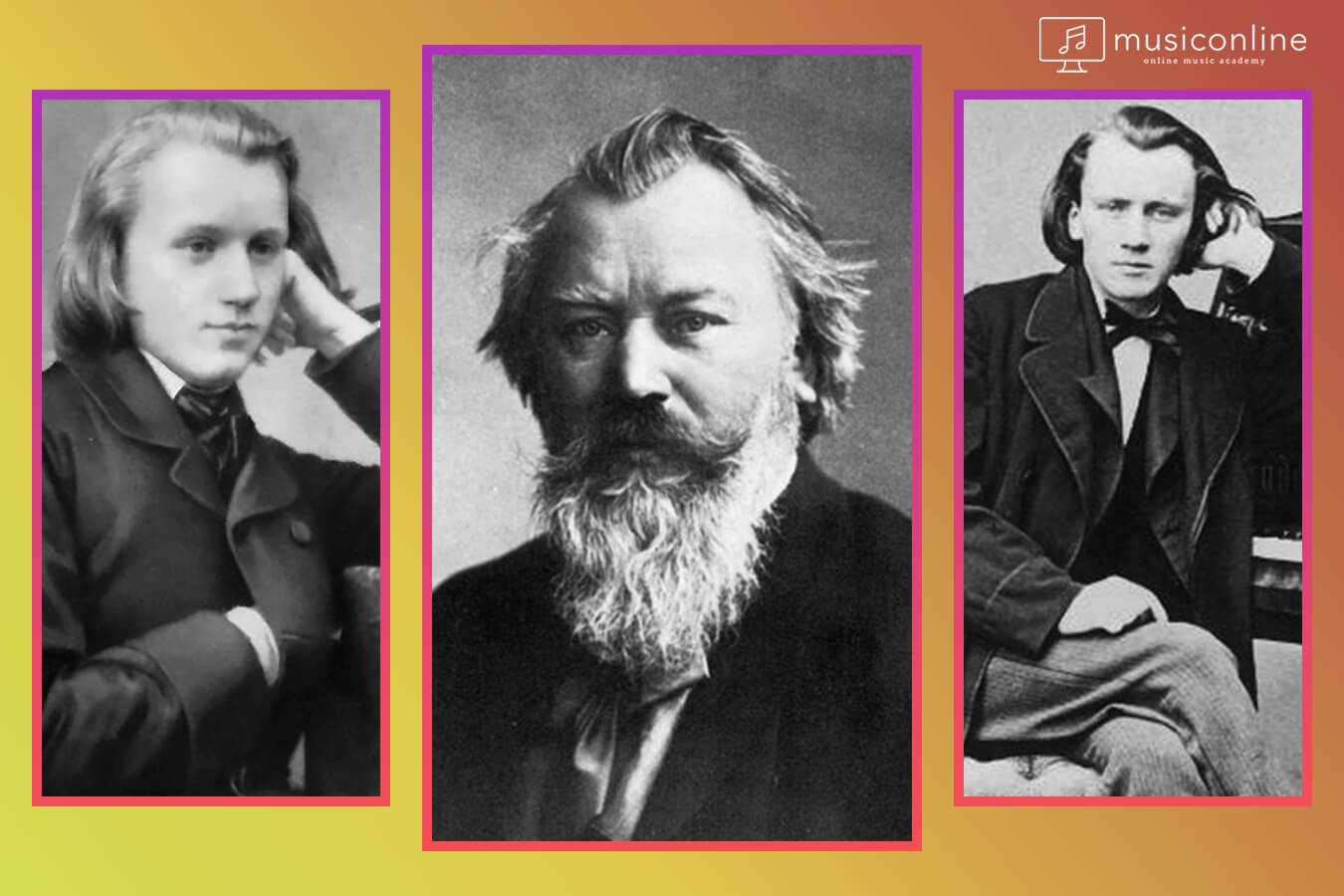

(1833-1897) German composer. By processing classical forms in a style influenced by Romanticism, it formed the last and highest point of the evolution of classical style and traditional music in the face of the 19th century's search for innovation. He was born on 7 May 1833 in Hamburg and died on 3 April 1897 in Vienna. His father, Johann Jakob, was a musician who played the double bass in the municipal theatre. He first took charge of his son's musical education, but when Johannes was seven years old, it became clear that he needed private lessons. At the age of ten, his teacher Otto Cossel turned to his teacher, Eduard Marxsen, one of Hamburg's leading music masters, to train him. Sensing Johannes' talent, Marxsen felt the need to focus not only on piano technique but also on composition subjects in lessons.

Johannes Brahms (7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, he spent much of his professional life in Vienna. He is sometimes grouped with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven as one of the "Three Bs" of music, a comment originally made by the nineteenth-century conductor Hans von Bülow.

Before long, Brahms began compiling small compositions and folk tunes. During this period, he had to attend concerts, work in nightclubs and sailor's taverns, and his health deteriorated in order to do his schoolwork on the one hand and to contribute to the livelihood of his family on the other. He spent the summers of 1847 and 1848 at a family friend's home in the country, working less and less.

At the end of 1848, he gave his first concerts in Hamburg as the composer Brahms. Since he could not achieve any significant success with these, he returned to ordinary work with the concern of livelihood. However, his meeting with the Jewish-Hungarian violinist Eduard Remenyi in 1850 and then listening to the famous violinist Joachim deeply affected the course of his life.

Remenyi and Brahms played together on concert tours for three years. This collaboration did not contribute to Brahms' art, apart from his close acquaintance with gypsy melodies. Brahms met Joseph Joachim at a concert in Hanover with Remenyi. The young artist was encouraged when this violinist spoke highly of Johannes' works.

Joachim had Brahms meet Liszt and then Schumann. Liszt took an interest in the young composer and wanted to include him in his circle. But Brahms left Liszt's side as he could not adapt to the formality and musical understanding of the Altenburg Palace in Weimar, where he lived. In turn, he formed a deep friendship with Schumann. In Schumann's diary on September 30, 1853, "Brahms came to see me today... a genius!" contains the whole. Schumann wrote an article in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik magazine, which praised Brahms. Six months after they met, Robert Schumann was put in a mental institution. Brahms cared for him until his death and supported his wife, pianist Clara Schumann, throughout his life.

In 1857 Brahms was appointed to a semi-official post in Detmold, at the court of the Prince of Lippe, with the help of his wide circle of Clara. He settled in Hamburg again in 1860. He organized a women's choir and assumed its management.

In 1862, the directorship of the Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra became vacant. Brahms was also one of the few people considered for this task. While waiting for the result of his appointment request, he went to Vienna for the first time. He stayed there for a while and gave a series of successful concerts. His friend Julius Stockhausen, a former singer, was appointed as the manager, showing why he was only twenty-nine years old. Meanwhile, he accepted the managerial proposal from the Vienna Singing Academy. He left this post a year later, but apart from travels and concert tours, he made Vienna his homeland until his death.

The artist was appointed chief executive of the Vienna Society of Friends of Music, which was vacated by Anton Rubinstein in 1872. He worked for three years in the best music organization in the city, conducting the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra as well as the choir.

He spent the last ten years of his life rather monotonous and uneventful. He was loved by large masses of people and attracted the attention and respect of many official institutions in various countries. However, the loss of three great friends was a source of great pain for him. These friends were the Austro-Hungarian emperor Franz Joseph, his once beloved Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, with whom he had a lifelong relationship, and his friend Clara Schumann. After Clara's death, Brahms entered a period of rapid decline. He died of liver cancer in 1897.

The most distinctive feature observed in Brahms' character, his behavior, was the peasantry. In fact, he was not of rural origin. He was born to a father who had migrated to the city from the secluded swamps of the Elbe River and a mother who was an urban worker. However, even when he was the emperor's chief friend throughout his life, he preferred to remain a peasant. The fact that he can control his passions, defend his thoughts and ideals with an uncompromising stubbornness, and that his genius is stagnant rather than bursting, stems from the dominant "peasantism" in his character.

Brahms never married. He was once engaged to Agathe von Siebold. When Agathe realized that the composer was constantly delaying her decision to marry, she broke off the relationship. The G Major Six, Piano Quintet, and the famous Wiegenlied (“Lullaby”) are products created during this time.

Brahms lived a sedentary life in Vienna, although he often traveled and went on concert tours as it gave him a sense of leaving his depression behind. However, despite being based in the Austrian capital, he was never Viennese. He remained a staunch German patriot with his life, views, and expectations. It can be said that he hates everything English and French. He was unaffected by the 1848 revolutionary movement, as his early youth was spent in Hamburg, far from the centers of conflicts, wars, and political activity. However, he watched the Franco-Prussian War day by day with increasing interest, and at some point, he made up his mind to enlist as a volunteer in the Prussian army. He worshiped Bismarck, who was called the "Iron Prime Minister", and spoke with hatred of Napoleon III, whom he called "the head of demons". He composed a pompous Victory Song on the victory of Prussia. This piece of little value has been forgotten.

Brahms had composed important compositions while he was giving concerts with Remenyi. These works, most of which are piano pieces and sonatas, are still included in concert programs today. Afterward, he continued to produce products mostly for piano and human voice. After completing his First Piano Concerto, which he first started as a symphony, in 1858, he did not compose orchestral music for fifteen years. In contrast, his productivity in piano, chamber music, choral works, and singing was always high. In 1873 he completed Variations on a Theme by Joseph Haydn. He made two adaptations of ten works, two for piano and two for orchestra. Thus, at the age of 40, he began to produce orchestral works again. Over a period of twenty years he has created outstanding examples of this field, such as the four symphonies, the Festival Overture, the Tragic Overture, the Second Piano Concerto, the Violin Concerto, and the Concerto for Violin and Cello.

Although Brahms was a very productive composer, this delay in his inclination to orchestral works can be thought of as related to his understanding of music. The composer was deeply fascinated by the greatness and values of the past. It seemed very difficult for him to be able to produce new and sophisticated works in the face of these values. It can be said that he needed to go through a long preparation period in order to turn to orchestral music. Brahms is extremely modest about this. He says, “If the people had not forgotten the works of those great masters in the past, neither I nor my contemporaries would have been able to make a living from composing”.

On the other hand, for all his humility, he believed that he was the person who best grasped the evolution of music. He directed his effort almost entirely to extracting and assimilating the main advantages of this evolution. He meticulously studied the works of previous masters; He consciously and persistently promoted them.

Such an attitude towards the evolution and future of music was quite different from and even opposed to, the leading composers of that time such as Liszt and Wagner. Liszt and his entourage were the focus of developments in the middle of the 19th century, which emphasized the pursuit of innovation and did not want to be bound by tradition. Along with Joachim, Brahms also took part in the "New German" school led by Liszt for a while but broke off ties with him by signing a manifesto against this trend in 1860.

During Brahms's lifetime, the music universe was divided into groups resembling political parties, with Wagner in the first place. He was accused of conservatism and sentimentality due to his adherence to the Classical movement tradition in thought and form. These extreme interpretations are the consequences of a kind of contention. Still, the difference between Wagner's predominantly dramatic art and Brahms' lyrical music is clear. Brahms did not show any affinity or interest in symphonic poetry, of which Liszt gave the first important examples, and programmatic music in general, and preferred the classical symphony form. Unlike Wagner, he did not write stage work. Although their works are loaded with a sensibility articulated with music, this does not change the fact that they were composed as abstract music. In this respect, Brahms differs even from Schumann, with whom he is quite similar in thought and emotion. Literary and visual elements often come to the fore in Schumann's music. In Brahms, on the other hand, a sense of form and harmony definitely predominates.

This tendency of Brahms brought with it his specialization, especially in classical forms and techniques. The composer always gave priority to creating a solid and coherent structure, a harmonious whole. However, it would not be correct to consider him only a great master of the classical style. Brahms was also influenced by the romantic tendency of his age and reached a competent expression level in the personal style that he developed. In this respect, he wanted to follow Schumann's suggestion and develop the possibilities of expression and freedom as much as possible by dominating the form.

Brahms' music can be compared to Beethoven's in some places in terms of the effect they evoke. However, emotions, emotions, and spiritual events are intertwined in Beethoven's music. It is not immediately clear which one will appear when, where, and how. In Brahms, a spiritual event is resolved at once and at length. While Beethoven's stylistic diversity and colorfulness differ from work to work, we cannot observe the same richness in Brahms' style. He is considered more of a calm, balanced thinker of music. On the other hand, behind this serenity, a power of expression ranging from humor to tragedy is perceived. Especially in his symphonies, he did not pay much attention to the idea of "influencing" and kept the structural development and orchestration concerns ahead. Nevertheless, his symphonies are considered a continuation of the Beethoven tradition and even bear tonal similarities with his symphonies. The theme of the last part of Brahms's First Symphony and the choral part of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony are almost the same. As a matter of fact, "Brahms-lovers" used the name "Beethoven's Tenth Symphony", which Hans von Bülow ascribes to this work.

The harmonic structure in Brahms' music carries contradictions. Although he preferred simplicity from time to time, an ornate, rich harmonic structure appealed to him like many 19th-century composers.

Brahms is not a period-opening composer. On the contrary, his efficiency is considered to have closed an era and had a kind of afterword. He never left the examples of the past and wanted to bring the strength he found in them to the most competent level. Thus, he seems to have left the composers after him alone with their innovative tendencies.