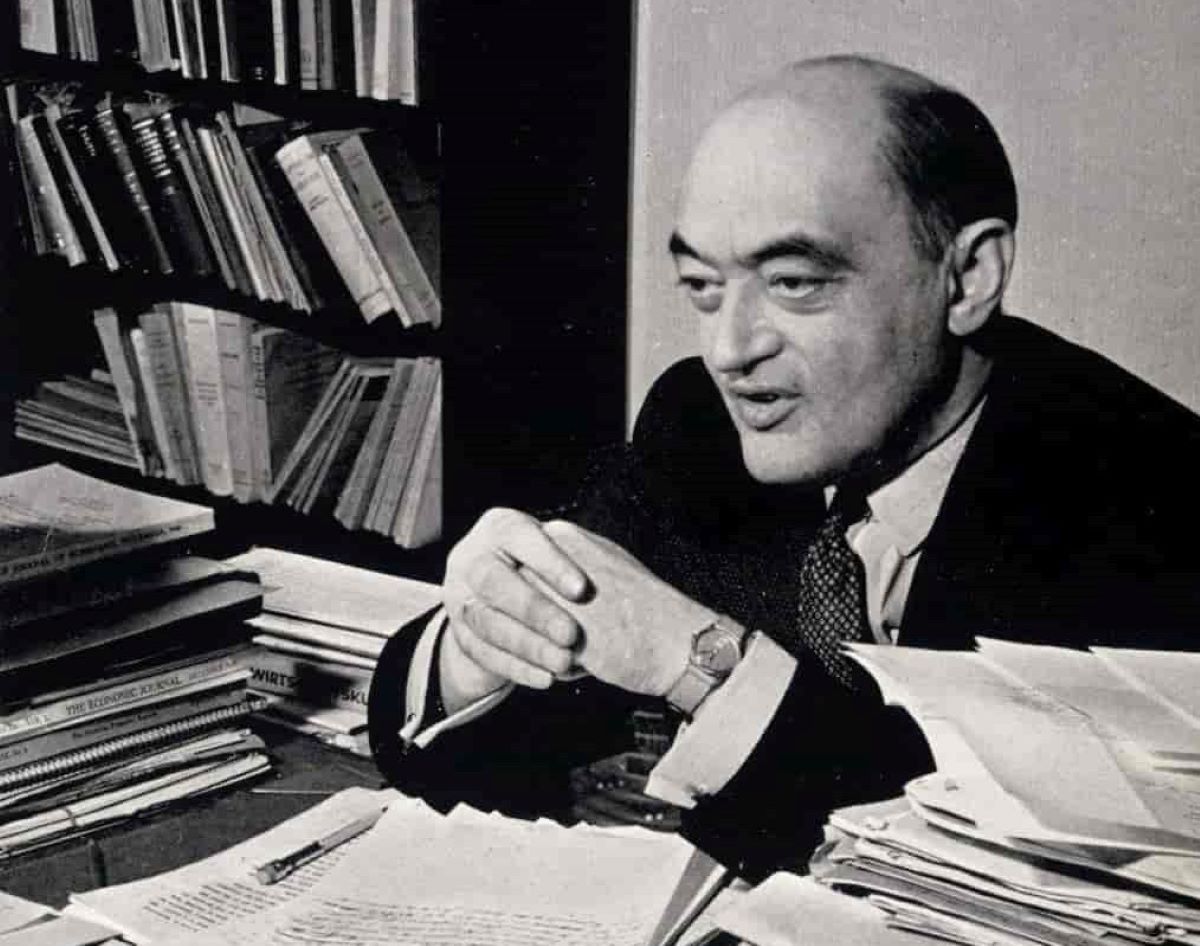

The economist who answered no to the question "Can capitalism survive?": Who is Joseph Alois Schumpeter?

The Austrian-born American economist did not explain the business cycle fluctuations in capitalism (such as bad harvests and natural disasters) with external factors but attributed them to technological innovations and the initiatives of businessmen. For Schumpeter, the force driving industrial development was capital.

Schumpeter was born in the provincial Austrian town of Triesch Moravia, the son of a clothier. When Schumpeter was four years old, his father died. His stepfather, an officer in the Imperial and Royal Army, whom his mother later married, sent the child to the elite Theresianum Lyceum in Vienna.

Schumpeter studied law and economics at the University of Vienna after 1901. He received the title of doctor of law in 1906. A year later, he married 24-year-old Gladys Ricarde Seaver, the daughter of a clergyman, whom he met on a trip to England. However, shortly after their marriage, the young married couples divorced (1920).

Joseph Alois Schumpeter (February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950) was an Austrian political economist. He served briefly as Finance Minister of Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States to become a professor at Harvard University, where he remained until the end of his career, and in 1939 obtained American citizenship. Schumpeter was one of the most influential economists of the early 20th century and popularized the term "creative destruction", which was coined by Werner Sombart.

Schumpeter went to Egypt in 1907 as a lawyer and as an officer of the International Arbitration Committee. In 1908, he wrote his book, Characteristics and Main Content of Theoretical Economics, which introduced him to the scientific community. Schumpeter criticized the mathematical methods of French economist Leon Walras on the grounds that his calculations did not include the reasons that led to the development and fluctuations of capitalism.

At the age of 26, Schumpeter held a chair at Chernovtsi University in the eastern part of the Austrian Empire. Two years later, he was appointed professor of economics at the University of Graz in Styria. Here he published his book Theorie der Wirtschafdichen Entwicklung (Theory of Economic Development) in 1912. Here, Schumpeter explained the internal dynamics of capitalism and thus followed in the footsteps of Karl Marx, whom he greatly admired.

The core concept in Schumpeter's work was "Innovation"; by this, he described any conceivable change in the provision of goods (new products, production methods, sales methods, sales markets). For him, innovation did not only consist of new products but also different production methods and new sales markets.

The concept of innovation also determines his entrepreneurial understanding. An entrepreneur is entitled to the name of entrepreneur only when he has creative power and opens new areas with his innovations. Schumpeter disdained people who were only company owners or managers, describing them only as "Owners".

Austria's Social Democratic prime minister, Karl Renner, appointed Schumpeter as finance minister in 1919. Schumpeter had to leave his post seven months after he started because the government blocked a nationalization project. The Biedermeier Bank in Vienna, of which he took over as manager in 1921, went bankrupt three years later.

In Bonn, where he moved with his second wife, Annie Resinger, whom he married in 1925, Schumpeter served as a professor of financial sciences.

Schumpeter settled in the USA in 1932. Schumpeter, who was appointed as a professor at Harvard University in Cambridge, expanded the business cycle theory there. Ten years later he published his work Capitalism Socialism and Democracy. In this book, he argued that capitalism would gradually give way to bureaucracy and that the transition to socialism with a planned economy was inevitable. Their basis: large trusts assuming the role of innovators and eliminating small entrepreneurs, salaried managers making guiding decisions based solely on sales planning.

Despite his scientific contributions, Schumpeter was a lonely man in the USA. The reason for this was the inappropriate words he said about Jews and those of the Slavic race. Hitler described Germany's loss of the war and surrender in 1945 as a "victory for the Jews." Schumpeter's failure to accept the Morgenthau Plan resulted in his complete rejection by the American public. He was unable to complete his last work, History of Economic Analysis, which is a balance sheet of economic thought starting from ancient times. He died of brain failure in Taconic, Connecticut, at the age of 67.

Schumpeter tries to clarify a question in his book Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1942); "Can capitalism survive?". Schumpeter clearly says, "No, I don't think so," and tries to explain why.

Schumpeter's answer to what comes after capitalism is socialism. However, unlike Marx, Schumpeter does not have positive thoughts about socialism. The advantages produced by private entrepreneurship, innovation, and capitalism are far superior to the results that would be achieved in a socialist economy. Furthermore, unlike Marx, Schumpeter does not support the replacement of the capitalist system with socialism. According to him, this change will not be positive for the welfare of society and will even cause noticeable declines in living standards.

Schumpeter says that the transition to socialism began in the 1940s when he wrote the book. As evidence, he points to rapidly increasing government regulation, controls on banking and the labor market, price regulations, calls for government control of industry, and so on.