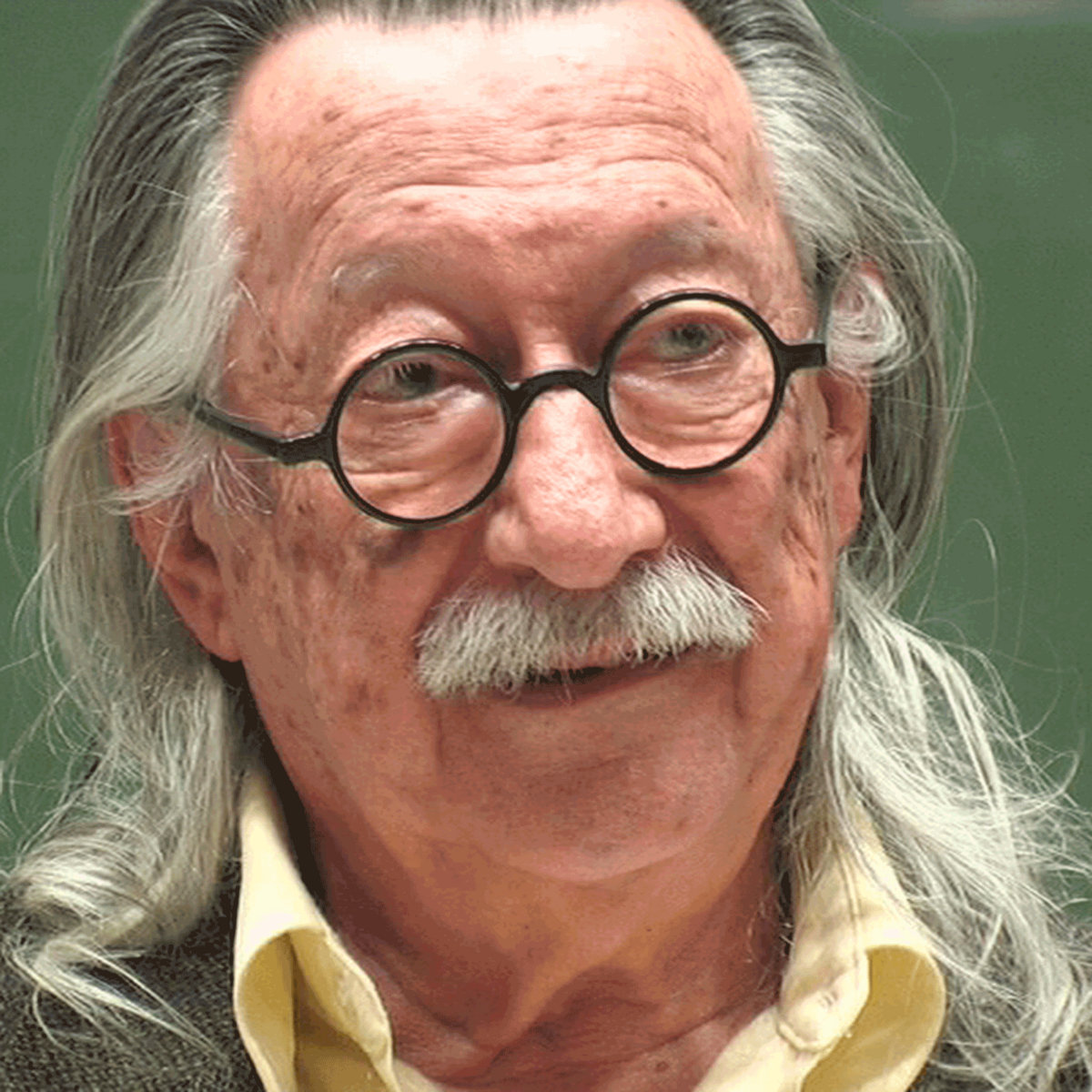

He had developed the world's first chatbot, became anti-artificial: who is Joseph Weizenbaum?

German-American computer scientist Joseph Weizenbaum broke new ground in technology 57 years ago by developing the world's first chatbot. However, later on, Weizenbaum turned into a complete anti-AI.

Joseph Weizenbaum, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), made history as the person who developed the world's first chatbot. Weizenbaum gave this software the role of psychotherapist.

Weizenbaum named the chatbot Eliza after the character Eliza Doolittle in George Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion. In the game, the poor flower girl Eliza was able to convince the people she was a duchess by using her language skills. Likewise, software called Eliza was designed to create the impression that it could understand the person sitting at the keyboard.

Eliza is still known today as one of the most important developments in computer history. Last year, ChatGPT's meeting with users increased the interest in Eliza even more. Articles about Eliza appeared in many newspapers and magazines.

Weizenbaum became one of the crackling voices in his field in the 1970s. Condemning the worldviews of his colleagues with his books and articles, Weizenbaum began to warn the world about the dangers posed by these studies. Because he thought that artificial intelligence was "the index of madness in our world".

The view that artificial intelligence is a threat today is not limited to a minority working in this field. Opinions differ as to which risks are of concern. But many well-known names such as Timnit Gebru and Geoffrey Hinton, both of whom have worked at Google in the past, share the view that the technology can be toxic.

Joseph Weizenbaum (8 January 1923 – 5 March 2008) was a German American computer scientist and a professor at MIT. The Weizenbaum Award is named after him.

These views of Weizenbaum were very relevant to his own past. Born into a wealthy and assimilated Jewish family in Berlin in 1923, Weizenbaum grew up with his father's insults that "an idiot like you is nothing". Hitler's election as chancellor in 1933 changed Weizenbaum's life. He had to transfer to a school attended only by Jewish boys, where he had the chance to meet Jewish children of Eastern European descent and to become acquainted with the ghetto culture through his friends. Once, when he invited one of these friends to his home, he faced the reaction of his father.

The family left Germany abruptly in 1936 and immigrated to Detroit, USA. Here, 13-year-old Weizenbaum turned into a fish out of water. He was buried in his lessons because he was so lonely. His favorite subject was algebra because it didn't require English, she. He saw mathematics as a completely abstract and very easy game. When he learned to use the lathe in his metalworking class at school, he realized that intelligence is not just in the head, but in the "hand, wrist, arm".

After high school, he attended Wayne University, a low-enrollment school filled with students who both work and study. The social consciousness that started to develop in Berlin became stronger here. He drew similarities between the experiences of Jews in Germany and black people in Detroit. At that time, labor movements in the city were also gaining strength.

BACK TO SCHOOL AFTER WWII

Weizenbaum wanted to study mathematics but felt that his desire to do something for society was incompatible with mathematics.

Conscripted into the army in 1941, he served as a meteorologist in World War II. After returning to Detroit, he got married, finished college, became a father, and got divorced. Weizenbaum, who experienced a deep depression during this period, thought that he could not achieve success in anything he did and that he was a worthless person. During this period, he became acquainted with psychoanalysis and computers.

During the war, a suitable environment was created for building large computers, with the help of these computers, the codes of the Nazis were broken and the most suitable angles to fire the cannons were calculated. After the war, the army was restructured, and in the first period of the Cold War, the money of the US government was spent on developing new technologies. In the late 1940s, the foundations of the modern computer were laid.

However, the computer was still not an easy thing to find. One of Weizenbaum's professors at the university had rolled up his sleeves to build his own computer and sought help from a group of students, including Weizenbaum. Building a computer gave Weizenbaum the happiness and sense of purpose he sought. Turning into a lively and enthusiastic person, Weizenbaum reunited with those abstract concepts he had known and loved in his algebra class in middle school.

Computers modeled and simplified reality, just as in algebra. However, he did it so authentically that it was possible to forget that what was in front of him was a representation. The software also gave people a sense of sovereignty. Weizenbaum compared it to the stage of a theater director.

GOT A JOB OFFER FROM MIT IN 1963

In the early 1960s, Weizenbaum began working as a programmer for General Electric in Silicon Valley. Weizenbaum, who developed a missile-launching computer for the U.S. Navy and a computer to process checks for Bank of America in the process, would say years later, "At the time, I didn't even realize I was supporting a technological venture that had certain social side effects that I would regret later."

In 1963, Weizenbaum was offered a visiting professorship from MIT. It was like, in Weizenbaum's words, "giving a boy who loves to play with toy trains the opportunity to work in a toy factory".

The computer Weizenbaum built in Detroit was a giant that filled an entire amp, requiring special rituals to use it. Computer scientists at MIT were looking for an alternative.

In 1963, the MAC Project was launched with a fund of 2.2 million dollars provided by the Pentagon. MAC had many expansions; one of them was "machine-assisted cognition". The aim was to create an accessible computer system that could meet the needs of individuals.

"TIME SHARING" CHANGED OUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE COMPUTER

For this, the "time-sharing" system, which we consider indispensable today, was perfected. Instead of loading punched cards into the machine and getting the result the next day, as in old computers, a structure was created where you get an answer as soon as you give the command. Moreover, thanks to individual terminals, many people would be able to use a single host. This made the machines feel more individual.

Thanks to time-sharing, a new type of software has emerged. The way people write programs has changed. Weizenbaum would later describe it as "people interacting with a computer in dialogue." The software development process had become a dialogue between the programmer and the computer. You were writing one piece of code and another piece based on the corresponding response.

But Weizenbaum wanted to take it a step further and have a conversation with the computer in a natural language like English. Eliza was born from that very idea, and thanks to its success, Weizenbaum was permanently on the staff of MIT in 1967. In this way, he had the opportunity to closely examine the MIT Artificial Intelligence Project implemented by John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky in 1958.

The term "artificial intelligence" was coined a few years ago by McCarthy, who was looking for a name for an academic workshop. Thanks to this name, artificial intelligence research was differentiated from similar fields such as cybernetics.

In an article he wrote in 1967, Weizenbaum argued that no computer can fully understand a human being, nor can any human fully understand another human being. He argued that differences in our upbringings and experiences limit our capacity to understand one another. Some things were impossible to communicate because different people could interpret the same word in different ways. This perspective, which was influenced by psychoanalysis, was very different from that of Minsky or McCarthy.

However, thanks to Eliza, it has been realized that it is very easy to create the feeling of "The computer knows me" in people. In his 1966 article, Weizenbaum talked about the negative consequences of this feeling, noting that people might see computers as "things with the judgment that deserves credibility," adding: "There is a certain danger lurking there."

At that point, Weizenbaum did little more than point out the danger, but thanks to the Vietnam War, he would realize what the next step he needed to take.

In March 1969, anti-war actions were being held at MIT. According to one activist, scientists felt that they were part of a great evil, and the massive protest on March 4 was the impetus for this.

Weizenbaum was greatly influenced by the political atmosphere of the period. As he later explained in an interview, the combination of the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, and MIT's role in weapons development strengthened Weizenbaum's critical stance. He thinks of the German scientists who served the Nazi regime and asks, "Do I want to play such a role, too?" he questioned himself. He was either going to put those thoughts aside altogether or do something serious about it.

WHAT JOBS CAN BE GIVEN TO COMPUTERS?

In 1976, Weizman published his masterpiece, 'Computer Power and the Human Mind: From Judgment to Calculation'. In the philosophical commentary on computers, Weizenbaum addressed his colleagues Minsky and McCarthy, as well as philosopher Hannah Arendt and author Eugene Ionesco, known for his experimental games.

The book had two main arguments. First, there was a difference between man and machine. Second, some tasks were not supposed to be assigned to computers, regardless of whether they could do it or not. The phrase "from judgment to calculation" in the title of the book connected these two arguments.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE EXCITEMENT TURNED INTO AI WINTER

'Computer Power and Human Mind: From Judgment to Computation', published at a time when computers were rapidly becoming widespread and politicized in government institutions, was a heavy blow to the artificial intelligentsia and provoked harsh reactions. Pro-artificial intelligence scientists criticized Weizenbaum with their articles, and he responded to these criticisms by writing new articles.

In the spring of 1977, the subject moved to the front page of The New York Times. "Can machines think? Should they? The computer world is in the midst of a fundamental conflict over these questions," wrote Lee Dembart.

Weizenbaum retired from MIT in 1988 and moved to his birthplace Berlin in 1996. His waning reputation in the USA grew in Germany. He often attended conferences and gave speeches.

Continuing to be hopeless about the future, Weizenbaum started to worry about climate change in the last years of his life. In his article published in Süddeutsche Zeitung in January 2008, he argued that what will save the world from the climate crisis is not science and technology, but resistance to global capitalism.

Weizenbaum, who died on March 5, 2 months after this article, was 85 years old and the cause of death was stomach cancer.