He made the first regular classification of animal species: Who is Louis Agassiz?

Agassiz started his studies in the field of fishology (ichthyology), where he made important contributions, in his youth.

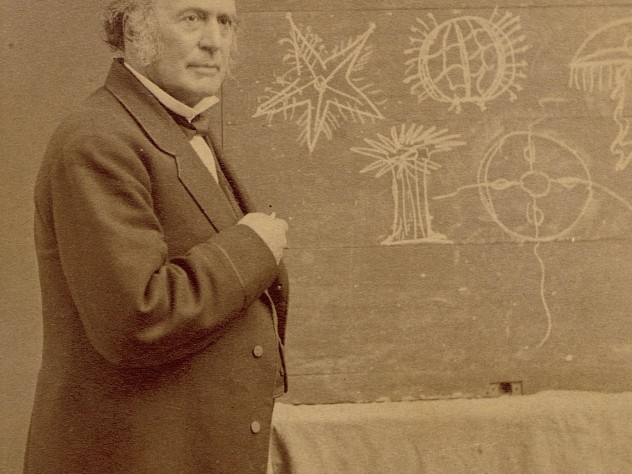

(1807-1873) Swiss-born US naturalist. He contributed greatly to the development of natural sciences with his studies of animal systematics, fossil fish, and glacial movements and made the first regular classification of animal species.

He was born on May 28, 1807, in the Swiss town of Mötier on the shores of Lake Morat. His father was a Protestant pastor who had been exiled from France to Switzerland. His mother, who instilled in him a love of animals and plants, was so influential in his life that his son became a naturalist.

After attending the universities of Zurich, Heidelberg, and Munich, Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz received his doctorate in philosophy from the University of Erlangen and in medicine from the University of Munich. Continuing his work especially in Switzerland and other European countries starting from the 1830s, Agassiz was invited to the USA in 1846 to give lectures. Two years later, he was made a professor of natural history at Harvard University, choosing American citizenship in 1861 and living there for the rest of his life. Louis Agassiz, who contributed greatly to the establishment of the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard and became the first director of the museum in 1858, died on December 14, 1873 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

His son, Alexander Agassiz, is also a naturalist known for his work in marine biology. Agassiz started his studies in the field of fishology (ichthyology), where he made important contributions, in his youth. An important event that provides him with extensive opportunities in this regard is that he was chosen for a team that studies Brazilian fish. In 1819 and 1820, two naturalists, Spix and von Martius made extensive trips to Brazil and returned with a rich collection of fish specimens, mostly from the Amazon river. Upon the death of Spix, who started classification studies on the fish species in these collections, in 1826, von Martius asked Agassiz to complete the project. Agassiz completed his classification studies in 1829 and published them under the name Selecta Genera et Species Piscium ("Selected Fish Species and Species"). While this work brought honor to the 22-year-old young scientist, it also gave direction to his future scientific studies in terms of content and method. Taking advantage of this experience, he collected the results of a project he carried out in the 1830s under the name of History of the Fresh Water Fishes of Central Europe in 1839-1842.

The year 1832 was the most important year at the beginning of Agassiz's scientific work. He went to Paris for the first time that year and had the opportunity to benefit from important research institutions in the field of medicine and natural sciences. He used to lead a poor student life in Paris; In time, he got help from the valuable scientists of his time and consolidated his situation in a short time. One of the first to assist Agassiz was the well-known French paleontology and anatomy scholar, Georges Cuvier. While working with Cuvier, he intrigued Alexander von Humboldt, the founder of scientific geography, and after Cuvier's death, Humboldt Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel (1832). Thus, Agassiz had the chance to continue his research with greater opportunities during his tenure that stretched back to 1846.

At that time Agassiz became interested in the extinct fish of Europe. Indeed, almost none of the fish species he studied, especially at Glaris in Switzerland and Monte Bolca near Verona in Italy, had been evaluated in such detail before Agassiz. Agassiz made the first plans for this extensive and important work in 1829, even before he went to Paris. As a result, he collected all the specimens he could find and published his work on the classification of fossil fish under the title Recherches sur les poissons fossiles ("Research on Fossil Fish") in 5 volumes between 1833 and 1844. The number of fish fossils named within the scope of this study reaches approximately 1700. In this way, both the characteristics of extinct fish and the conditions of the extinct species in ancient times were brought to light. Turning his attention to other extinct sea creatures, Agassiz published Etudes critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (“Critical Treatises on Fossil Mollusks”) between 1841 and 1842.

In addition to his studies on the classification of animals, Agassiz also conducted very important research on the movements and effects of glaciers. Some geoscientists have suggested that ice rivers in Switzerland were once much more widespread and that irregular moving parts broke off from the main structure and spread out into the environment. Agassiz built a cottage on the Aar glacier between 1836 and 1837 and spent his summer vacations here, studying the structure and movements of the glacier with his colleagues.

After all, he believed that the glaciers were mobile, and he assumed that the rocks around the glaciers were due to this movement. In 1839, he had the opportunity to prove his conjectures with his experiments on a glacier. Once it was proven that glaciers were mobile, it was also possible to assume that these glaciers had spread over larger areas in the past. Agassiz suggested that regions with scratched, corrugated and shiny-surfaced rocks that no longer have a glacial layer on them were once covered with glaciers. By including these assumptions in Etudes sur les glaciers (“Investigations on the Glaciers”), which is considered one of his most important works, published in 1840, he suggested that there had been an “Ice Age” long ago when a large part of Northern Europe was covered with glaciers. . This important work explains how slow but widespread environmental changes occur. Such research, which Agassiz later continued in North America, shows that this continent also experienced an ice age similar to that in Europe.

Agassiz was also a good teacher and a very effective speaker. In 1846, at the invitation of the well-known English geologist Charles Lyell, he went to Boston to give a series of lectures. He continued his educational seminars, which he started at the Lowell Institute in Boston, with conferences he gave in many cities in the USA. Agassiz owed his success on this subject to his impressive physique as well as his knowledge, his convincing and dominant attitude on the podium, and his ability to establish a good dialogue with a large audience. With his conferences and scientific articles in journals, he became one of the most well-known scientists in the 19th century who brought science to the public. A Journey in Brazil (“A Journey in Brazil”), which he wrote in 1868 with his second wife, the educator, and writer Elizabeth Cabot Cary, is a very successful example of dealing with natural science topics at a level that everyone can follow with interest.

The natural science organizations created by Agassiz's efforts are as important as his works and lectures. The summer school for marine studies he founded after the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, although it did not survive his death, set a good example for later initiatives.

The impact of Agassiz's work on animal classification and fossils is important in two ways. On the one hand, it created an interest in fossil studies, and on the other hand, it helped to establish the evolutionary relationships of living things by bringing order to the turmoil in which the science of zoology was, and provided the power to support the natural selection phenomenon in Darwin's theory of evolution. However, Agassiz never accepted this theory and was known as an anti-evolutionist scientist in the USA at the time.

WORKS (mainly):

Selecta Genera et Species Piscium, 1829, (“Selected Fish Species and Species”);

History of the Fresh Water Fishes of Central Europe, 1839-1842; (“History of Freshwater Baskets in Central Europe”);

Rercherches sur les poissons Fossiles, 5 vols, 1833-1844, (“Research on Fossil Fish”);

Etudes sur les glaciers 1840, (“Explorations on Glaciers”);

Etudes critiques sur les mollusques fossiles, 1841-1842, (“Critical Reviews on Fossil Mollusks”);

Contributions to the Natural History of the United States, 1857-1862, (“Contributions to the Natural History of the United States”);

Essay on Classification, 1859, (“A Study on Classification”);

A Journey in Brazil, (with E.C. Cary-Agassiz) 1868, (“A Journey in Brazil”).