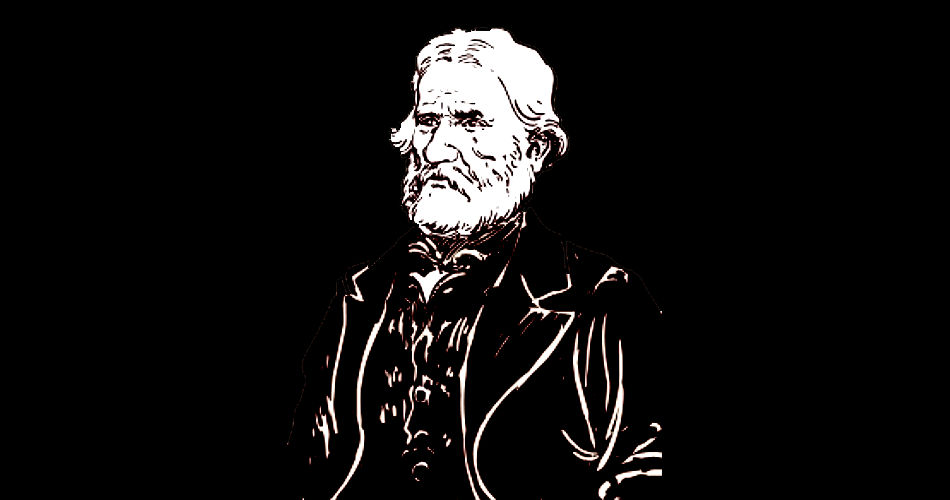

The man who seeks an answer to the question of how to make a revolution: Who is Louis Auguste Blanqui?

Louis Auguste Blanqui, a man of action who pursued revolution throughout the 19th century, came back from the brink of death several times for this cause and rotted in jail for 33 years. New research reveals that he is much more than a "poor coup plotter."

Blanquism was one of the biggest accusations that revolutionaries leveled at each other in the early twentieth century. Lenin Narodniks; Rosa Luxemburg and Plekhanov Lenin; Bernstein, on the other hand, accused all revolutionary Marxists of "Blanquism". When we look at the writings of Lenin, we understand what is understood by Blankism in this period: a strategy consisting of conspiracy, adventurism, and seizure of power by a minority. And Blanqui himself is responsible for this situation.

Louis Auguste Blanqui (8 February 1805 – 1 January 1881) was a French socialist and political activist, notable for his revolutionary theory of Blanquism.

Immediately after graduating from high school, Blanqui joined the Carbonari movement, which emerged in Italy, and began to engage in activities against the Bourbon dynasty in France. Having met the works of Fourier and the late works of Saint-Simon in the late 1820s, he did not accept their and their followers' dreams of peacefully forming utopian communities, yet he developed his egalitarian ideas inspired by the works of revolutionaries like Buonarroti as well as utopian socialist literature. He advocated materialism influenced by 18th-century thinkers such as Helvétius and d'Holbach, against the religious and mystical orientations that marked the work of utopian socialists (and Etienne Cabet, whom he would later read).

Before Marx there was

Louis-Auguste Blanqui was born in France in February 1805, one of eight children to an Italian father and a French mother. His father was a civil servant who was more or less involved in politics and even spent ten months in prison for it. Between 1818 and 1824, Louis Auguste underwent an intensive education: he studied Greek, Latin, geography, and history. He clearly stood out from among his schoolmates. During this period, his elder brother Adolphe, who was an economics teacher in Paris, wrote in a letter to his father that “this boy will shock the world”; it's what he said. Of the rather large Blanqui family, the most well-known was Louis Auguste, and his younger name was forgotten, and he was called Blanqui for short. In fact, the political current called by this name spread for a long time and beyond the borders of France.

Blanqui started life as a riot technician, raising his head at the age of nineteen from the books he eagerly and excitedly closed over. He founded many organizations in his long life; he spent many years in prison; he was wounded several times by the sword and once by a bullet in the battles, at the barricades; none of them stopped him. He always preferred the smell of gunpowder to the smell of ink and books; the rifle touched his hand more than the dipstick.

Although Blanqui did not abandon his fondness for books, which he met at a young age, he never stopped short of belittling and humiliating bookworms, those who were interested in academic debates or "opposing politics with little risk"; often received the same response from them. This attitude of Blanqui evidently played a considerable part in his refusal to meet with Marx, who made many attempts to contact and negotiate with him.

A Long Revolutionary Life

Unlike many of his comrades, Blanqui died in 1881, having lived quite a long time. During his long life, he witnessed the most important political upheavals in the history of France. Perhaps it would be more accurate to emphasize that these developments were not objective developments that coincided with Blanqui's life. Because, from 1824 to 1881, at one end of every action directed against the state in France was Blanqui or an organization under his influence in one way or another.

The first large-scale examples of these begin with his joining the French Carbonari organization in the early 1830s. He participated in student protests against the Bourbon monarchy, and when the July Revolution of 1830 broke out, Blanqui, a utopian socialist who was a writer for the Saint-Simonist Globe, left his office as soon as he heard that the people were taking to the streets. He mingles with the crowd, waving his rifle and the tricolor French flag. While fighting in the 1830 revolution, he was wounded three times and received a medal.

Blanqui's Uprising Strategy

The 1839 uprising was a unique application of Blanqui's theory of insurrection. Although about 500 armed revolutionaries captured the government building in Paris, they were defeated after a two-day battle as they did not receive the support of the people.

A revolution, in Blanqui's thought, was a well-organized group of armed revolutionaries who carried out a coup to seize power at the right moment, followed by a popular uprising. That is why Blanqui chose not to prepare the masses for revolutionary action, but to prepare a narrow group for revolutionary action. However, the people did not give their hand to their "commanders and soldiers", as Blanqui had called out to the people in 1839.

Although suppressed in a short time, this action, which made the Paris police sweat for six months due to the activities of those left behind, especially Blanqui, was also an important turning point for the German Blankists under the umbrella of the Union of the Righteous, to move away from Blankism and approach Marxism.

Blanqui's sentence, along with his comrade Barbés, after the 1839 uprising was clear: execution. Although the death penalty was commuted, Blanqui was released from prison nearly nine years later, just before the February Revolution of 1848. This time, he carried out a policy that forced the provisional government established in the 1848 revolution to follow a socialist and Jacobin policy. However, rumors about his former comrade Barbés significantly reduced his effectiveness.

He Was a Revolutionary Who Never Tamed

Blanqui had to watch the Commune's defeat, as well as its victory, from behind bars. Blanqui was in prison when thirty thousand communes were shot, and he was alive, albeit badly in health. His exile sentence to the labor camp in New Caledonia (this place of exile, which became famous thanks to the «Butterfly» is quite old), was canceled due to his old age and health condition. Released by a general amnesty in 1879, Blanqui was seventy-two years old and still a revolutionary.

However, in the last years of his life, Blanqui did not participate in or lead any action similar to the previous ones; The last great action marked by Blanquism in Europe was the action crowned with the Paris Commune. Although he often struggled with health problems after 1879, Blanqui did not hesitate to publish various newspapers and his anger never subsided. The most famous of the newspapers published during this period was called "Neither God nor Master".

Blanqui was not tamed for the rest of his life. At a workers' meeting he attended three days before his death, he was the only person to argue that the color of the flag should be red, against the so-called socialists who defended the French tricolor flag. When he returned home in anger after such an argument, during a heated conversation, he suffered a sudden cerebral hemorrhage, and after saying a few meaningless sentences, he remained silent forever.