The first representative of the Surrealism movement in cinema: Who is Luis Buñuel?

Buñuel embraces the liberation of sexuality, the power of the subconscious, and the epoch-making character of the Surrealist program in all his films against the false sentimentality and moralism of the bourgeoisie.

(1900-1983) Spanish film director and screenwriter. He became one of the first representatives of the surrealism movement in cinema and one of the masters of European cinema. He was born on February 22, 1900, in the Saragossa region, and died on July 29, 1983 in Mexico City, Mexico. He is the son of a cultured Spanish bourgeois family. He was sent to the Jesuit school at an early age. He was influenced by Spanish Catholicism during his childhood and youth.

The skin and anti-religion opposition that he deals with in many of his films can be explained by the effects of this learning. He stated that while he was a good student at school, he led a life outside of school that contradicted his religious education. Between 1920-1923, he studied at the University of Madrid. He met Salvador Dali and Federico Garcia Lorca. He went to Paris in 1925. After seeing Fritz Lang's Der Mude Tod ("The Tired Death"), he decided to take an interest in cinema. He studied at the Academie du Cinema. He started in cinema as Jean Epstein's assistant. He assisted Epstein in the films Mauprat and La Chute de la Maison Usher ("The Collapse of the Usher Mansion"), and Etievant and Malpas in La Sirene des Tropiques ("The Sirens of the Tropics").

Buñuel, who soon fell out with Epstein, made his first film in 1928 with money sent by his mother: Un Chien Andalou ("The Andalusian Dog"). This film is also Buñuel's first collaboration with Salvador Dali. Based on the automatism principle of Surrealism, the film is designed as a series of jokes that have no logical relationship with each other. Some sarcastic or startling images are transmitted as they come out of the subconscious. Many of these are in a thematic unity with the images in later Buñuel films.

Despite Epstein's warning, Buñuel continued his collaboration with the Surrealists. 1930s l'Age d'Or (The Golden Age), the product of his second collaboration with Dali, was banned as soon as it premiered at Studio 28 in Paris. The film developed the "crazy love" theme of the Surrealists, as well as the sense of fiction in its first film. This theme was enriched with references to the Marquis de Sade, showing the destruction of the social order of sexual desire and love. In the movie, which opens with a scorpion fight, a "rebellion-established order" opposition was established between the bandit-led gang, played by the surrealist painter Max Ernst, and the archbishops. The protagonist of the movie saw sexuality everywhere and showed a series of surrealistic reactions due to the inability to satisfy sexual desire.

Buñuel was in Hollywood during the Golden Age scandal. He worked on the script for a movie called The Beast With Five Fingers and for a while as a researcher at the Museum of Modern Art. When he returned to Spain in 1932, he started making a documentary film called Las Hurdes ("Land Without Bread"), about the people of the poor Las Hurdes region of Spain, with the money he won from the lottery. In this film, the sick, the desperate, and the day-to-day depleted people are presented in contrast to the ostentatious opulence of the church. The opposition between church and people, which would be of great interest to Buñuel, becomes a social criticism. Due to the reactions it received, the film had limited screening opportunities.

After that, he contributed to the editing of the movie Madrid'36, which was about the Spanish Civil War. He was summoned to New York to shoot films against the Nazis and documentaries for the American military. According to Buñuel's words, this plan did not come true after Dali declared that he was an atheist. Between 1944-1946 he worked as a producer at Warner Bros. He went to Mexico in 1947. There he shot two market films for Mexican producer Oscar Danguircs: Gran Casino and El gran calavera (“The Big Mad”). The same producer then allowed him to make one of his greatest films, Los Olvidados ("The Lost"), without preconditions, in 1950. This film, which won the best director award at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival, was about juvenile delinquents in the Mexico City ghettos. Buñuel featured intense violence when describing a child being ruined by another child. This violence, which developed with the dominance of the destructive forces in society, was also reflected in the drawings of the other movie heroes. Los Olvidados was a film that combined Buñuel's distinctive mix of violence and sexuality with social criticism.

In Mexico, Buñuel had now proven his mastery and gained a certain independence. Subida al cielo ("Towards the Heavens"), which he translated in 1951, was an adventure film with melodramatic influences.

The only film the director made in English in 1952 was an adaptation of an English novel, Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe. In this movie, bugs, string, etc., which has become a passion for Buñuel. There were certain symbols and dreams such as Buñuel, who says that he "loves the hero, not the novel", examines the relationship between Crusoe and Cuma in the film. Here the traditional master-slave relationship reaches the reality of a human relationship. Following this in 1952, the director ("O") returns to the subject of the destructiveness of love, and Abismos de Pasion ("Abyss of Passion"), one of the adaptations made from the novel of English writer Emily Bronte, again directly deals with "crazy love".

The last and most important of Buñuel's highly prolific Mexican-era films is 1955's Ensayo de un Crimen ("The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz"). Packed with dark humor and a twisted sense of sexuality, this movie is a variation of Landru. Archibaldo de la Cruz, a female murderer psychopath, is thwarted by the fact that his chosen victim disappears in another death in every murder attempt. The movie is full of Buiuel symbols such as women's shoes, insects, and Viridiana wedding dresses. Here Buñuel both maintains surrealistic themes and mocks them. The film is basically about a man who is imprisoned by himself and his thoughts. Like some of the later Buñuel heroes, Archibaldo is the expression of an impotent personality.

Buñuel returned to France in 1955. The first film he shot here was Cela s'appelle l'aurore ("It's called Dawn"). Continuing the themes of social conflict and friendship in arms, the film dealt with a revolutionary subject. In 1956, the following La Mort en ce Jardin ("Death in This Garden") tells the story of a group of fugitives. In the film, a prostitute, a priest, a young girl, and an adventurer fleeing the wrath of a town tyrant are used to summarize traditional Buñuel oppositions. The priest character here realizes that during the development of the film, he cannot be in contact with the outside world and live as an exemplary Christian.

The director dealt with the same subject in his next film and one of his most important works, Nazarin (1958). Priest Nazarin, who has withdrawn from worldly pleasures, lives following the principles prescribed by religion. However, every business he undertakes with good intentions fails, and his piety cannot be evaluated by those around him.

Finally, as the criminal Nazarin walks away between the two gendarmes in a kind of renunciation, a peasant woman first presents him with a "gift", a pineapple. In a statement about the film, Buñuel stated that he deliberately emphasized the ambiguity of the Nazarin type. Nazarin can be seen as a criticism of Christianity as well as a modern interpretation of Jesus. The types around Priest Nazarin were completing and explaining the hero of the movie. Standing somewhere between the rider Binto's openness to bodily pleasures and the dwarf Ujo's Jesus-like humanity, Nazarian is a thinker who insists on his action. But like Archibaldo and the others, he is not certain about his thoughts. The miraculous semi-random relationship he has with his surroundings also stems from this. The film received the special jury award at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival.

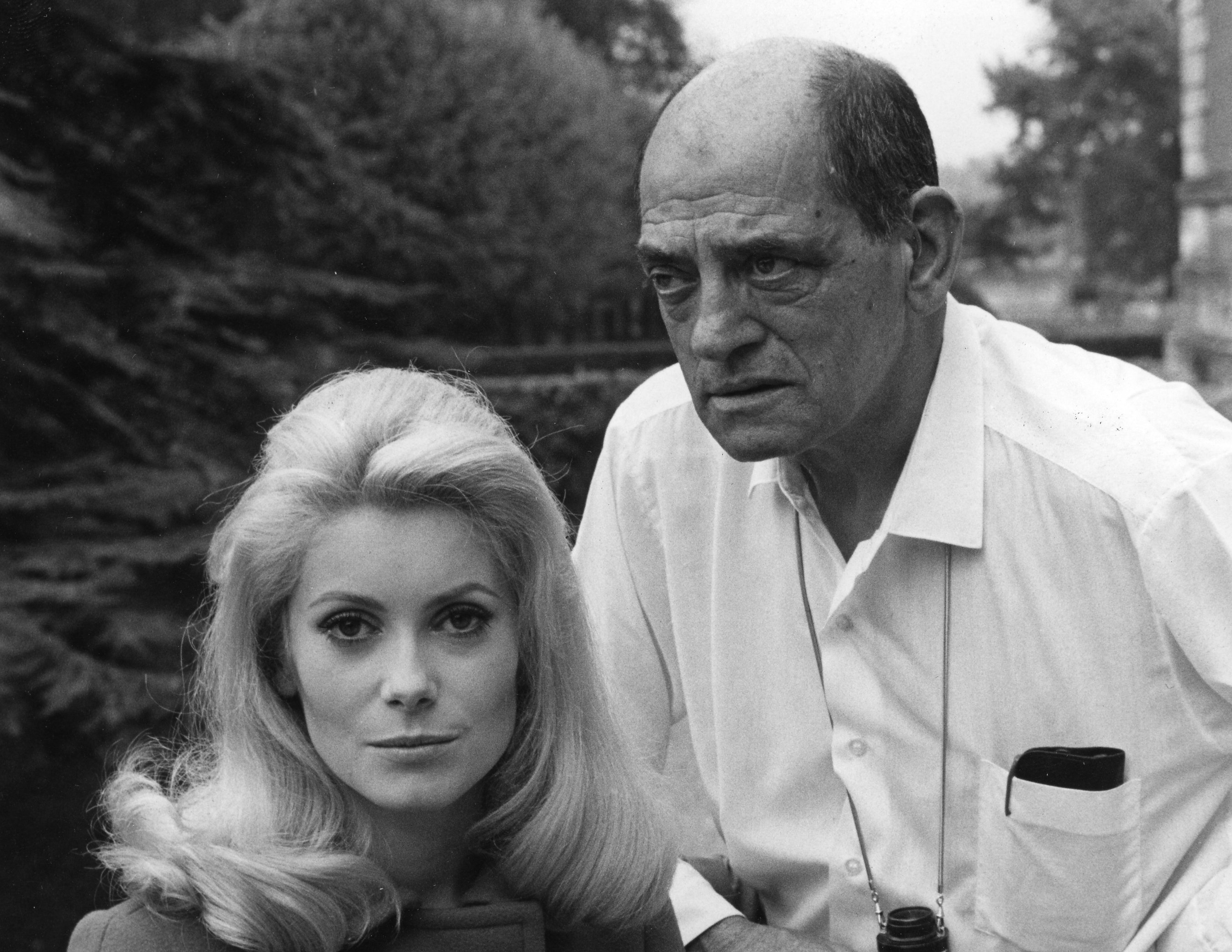

Belle de Jour (Day Beauty), shot by Buñuel in France, is the first of the successful co-productions in the last period of the director. Severine (Catherine Deneuve), happily married to her wealthy and handsome husband, learns the address of a Parisian appointment house from a family friend (Michel Piccoli). Having an irresistible desire to work there, the young woman starts going to the appointment house during the day. Before long, a gap widening with imaginary elements opens between the life she leads here as a “daytime beauty” and her life outside. In the film adapted from Joseph Kessel's novel, the criticism of bourgeois moralism is much more brutal than in the novel, and the main subject is again the obscurity of sexuality. Severine's hostess, husband, family friend, troublemaker, and relationships with various clients are like different faces of hers. The "atonement" incident at the end of the movie should also be considered relative salvation for Severine.

Tristana (1970) is Buñuel's first film in Spain after Viridiana. Tristana (C. Deneuve), who comes to live with her uncle, cannot stand his insistent sexual intimacy and runs off with a painter. But upon the painter's death, his uncle returns home with one of his legs amputated. Tristana is somewhat reminiscent of Viridiana in terms of plot, and a little bit of Beauty of the Day. Tristana's transformation from a vibrant, beautiful young girl into a painful, crippled woman once again underscores the impossibility of absolute innocence.

In Le Charme diseret de la bourgeoisie ("The Secret Charm of the Bourgeoisie"), another French production from 1972, he returns to episodic, surrealistic film fiction. The film is the story of a group of big bourgeois, who come together for a meal but cannot find the opportunity to have a meal. Reminiscent of the El Angel exterminador, the film was an original masterpiece of the social satire tradition. The same plot appears in Le Fantöme de la Liberte ("The Ghost of Freedom") in 1974. While the protagonists of the movie live different events together, they cannot break away from each other, and the narrative structure consists of the imaginary addition or interruption of events.

Buñuel says that there is no change in his thoughts from his first film, Un Chien Andalou, to his last film. He adopts the liberation of sexuality, the power of the subconscious, and the groundbreaking character of the Surrealist program in the first period in all his films against the false sentimentality and moralism of the bourgeoisie. Although Dali and some of the other Surrealists are dying out, Buñuel covers a wide spectrum (social realism, documentary, commercial cinema, etc.), not just Surrealism, and is considered the greatest and most "young" of the pioneering filmmakers.