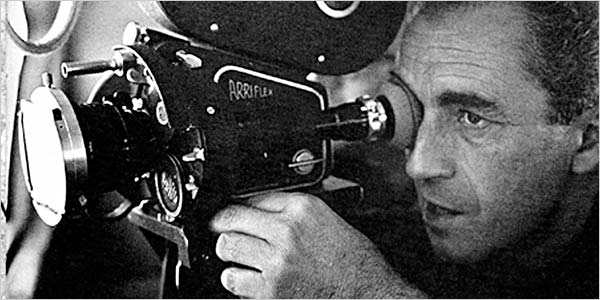

One of the most important pioneering directors of European cinema: Who is Michelangelo Antonioni?

He started cinema by adhering to the neo-realism movement, especially the documentary narrative of this movement, and later imposed his own themes.

Italian film director and screenwriter. He started cinema within the neorealism movement; He became one of the most important creative directors of modern European cinema. He was born on September 29, 1912, in Ferrara. His interest in theater and cinema began while he was at the University of Bologna. Later, he wrote cinema articles for a newspaper in Ferrara. He continued this work until the end of the 1930s, especially by criticizing the Hollywood wannabe "white telephone" period Italian films. He settled in Rome in 1930 and began writing film reviews for Cinema magazine. The following year, he entered the film direction department of the Centro Sperimentale film school as a student. Apart from his first documentary attempt on the mentally ill, which he did not have the opportunity to complete, his filmmaking career began in 1942 as a screenwriter and assistant director. During his apprenticeship, he worked with directors such as Rossolini, Fulchignoni, and Carne.

Michelangelo Antonioni Cavaliere di Gran Croce OMRI (29 September 1912 – 30 July 2007) was an Italian director and filmmaker. He is best known for his "trilogy on modernity and its discontents"—L'Avventura (1960), La Notte (1961), and L'Eclisse (1962)—as well as the English-language film Blow-up (1966).

Antonioni's 1943 directorial debut, Gente del Po ("People of the"), suffered some misfortune at the lab stage. It was only released in 1947, with editing made from remnants of film. After the assistant director of De Santis' film Caccia Tragica ("The Haze Hunt"), Antonioni made two short films in 1948. He worked with the musician Giovanni Fusco, with whom he would later collaborate, on these films, one about urban cleaners and the other about rural superstitions. In the short film that followed in 1949, L'amorosa menzogna ("The False Lover"), the exposure of the scandalous press, which was the main theme of Antonioni's films of this period, takes place for the first time. The same environment is the subject of Fellini's film Lo Sceicco Bianco ("The White Sheikh"), where he works as an assistant director. Unlike Fellini, Antonioni expresses his reaction to the vulgarity of art while criticizing false values and illusory grandeur. After shooting three more short films, the director had the opportunity to shoot his first feature film in 1950. With this movie called Cronaca di un Amore (“A Story of Love”), Antonioni breaks off his ties with neorealism and begins to establish his own unique cinematic understanding. The endless street views, camera movements, the unsolved mystery theme, and the intense erotic relationship between the lovers in the film, which tells about a murder involving a rich woman and her poor lover, will later become typical Antonioni concerns.

Antonioni proved his true talent with the trilogy he started with L'Avventura ("Adventure") in 1960. In this film, it is told that a woman goes ashore and disappears after an argument with her husband on a yacht trip, and her husband tries to look for his wife with another woman on the yacht and falls in love with her in the process. The simple and ambiguous nature of its subject led to many discussions. The film, which some critics found monotonous, gained international success as a result of the attention it received at the Cannes Festival. The rhythm provided by the montage, the use of the widescreen, and the thoughtful camera movements made L'Avventura a masterful film. The characters were presented successfully in terms of their relations with outer space, the atmosphere was successfully established, and dramatic plays such as unsolved secrets were used. Topics such as not escaping from the examples suggested by society in the relations between people and the individual's submission to materialistic values were discussed.

The second film in the trilogy was 1961's La Notte (“The Night”). La Notte, which tells the twenty-four hours spent together and separately by a couple whose marriage did not work out, is the story of a marriage and social environment at a dead end. There seems to be no dramatic conflict in the movie.

L'Eclisse ("Solar Eclipse"), translated in 1962, was considered the final film in the trilogy as it complemented the plot continuity of the other two films. This time, the space-person relations were carried over to the views of the city of Rome, and the closing sequence consisting of fifty-eight squares was the summary of the relationships of the couples Antonioni's subject. The conversation is minimized; the first and last seven minutes of the movie were deprived of speech. The outside world was perceived and presented as still, lifeless, and dull architectural structures.

The pictorial representation of physical alienation reaches its extreme with Il Deserto Rosso (“Red Desert”), the director's first color film attempt. The subject of the film is a woman on the verge of madness, living in an industrial area with her engineer husband, who has an emotional relationship with another engineer and clarifies her situation in this relationship. In the film, while grays, whites, pale reds, and greens alienate the heroine, dream episodes and moments of hope are drowned in bright colors. Antonioni's reduction of alienation to an almost aesthetic level gave Il Deserto Rosso a kind of pictorial abstraction.

In the following years, Antonioni turned to productions outside of Italy. He continued his stylistic research with the Red Desert in his second color film Blow-Up (I Saw the Murder), which he made in accordance with his contract with MGM in 1965. The film is about a successful fashion photographer taking pictures of two lovers in one of London's parks, and later on, when the woman lover who comes to his studio insists on taking over the negative of the photograph, he becomes suspicious and enlarges the photo in his hand, and falls on the trail of the woman, realizing that murder is in question from a stain he sees in the photograph. However, in the end, the reality of the murder, the woman, and increasingly what is going on in the film will be questioned. Antonioni chose London for this film, the "pop" scene of the late 1960s, full of marijuana, music, and fashion. The film, which turned into research on the quality of reality, was also a period film. The concern of evaluating color in terms of style also predominates in Blow-Up. The dark green of London's parks and the trees that the director has especially "painted white" are the visual complements of the quest and mystery theme in the film.

Michelangelo Antonioni is a film artist who summarizes the intellectual and artistic adventure of European cinema since World War II. He started cinema by adhering to the neo-realism movement, especially the documentary narrative of this movement, and later imposed his own themes. In his films, the uneasiness and hopelessness arising from the relations between the people of contemporary society have gained a pictorial intensity and an existential meaning.

WORKS:

Cronaca di un Amore, 1950, (“A Love Story”);

La Signora Senza Camelie, 1953, (“The Woman Without the Camellia”);

Le Amiche, 1955, (“Female Friends”),

II Grido, 1957, (“The Scream”);

L'Avventura, 1960, ("Adventure");

La Notte, 1961, (Night);

L'Eclisse, 1962, ("The Eclipse");

IlDeserto Rosso, 1964, (“Red Desert”);

Blow-Up, 1967, (“I Saw Murder”)

Zahriskie Point, 1970, (“Zabriskie Point”);

Chung Kuo-China, 1973, (“China”);

The Passenger/Profession: Reporter, 1973, (Passenger);

Le Mystere de Oberwald, 1981 (“The Mystery of Oberwald”);

Identificazio-ne dune Donne 1983, (“The Identity of a Woman”).