The rebellious spirit of Japanese cinema: Who is Nagisa Oshima?

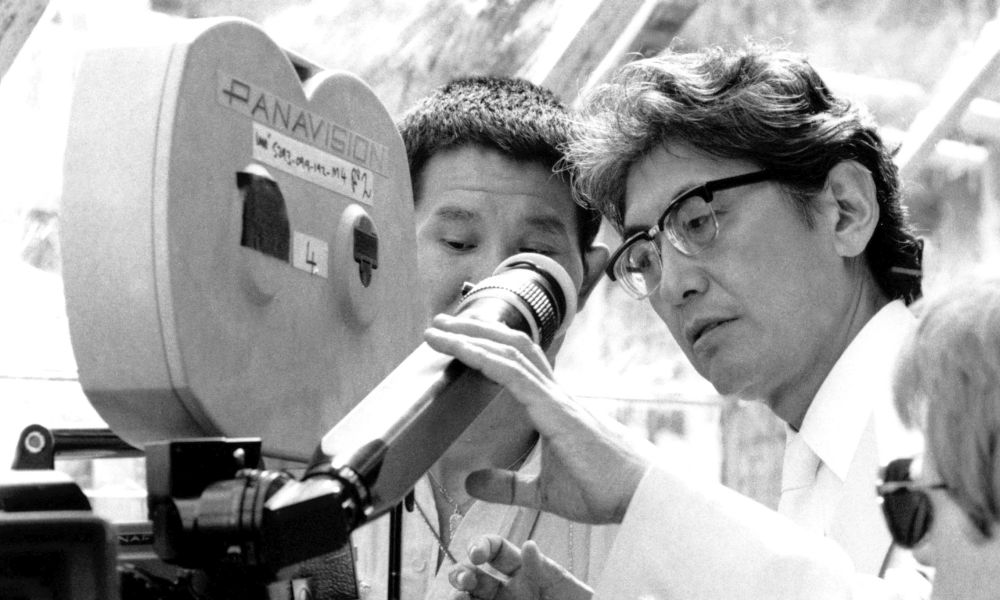

Nagisa Oshima, one of the names that left a deep mark on Japan's cinema history, is known not only for the innovations he brought to the art of cinema but also for his bold and provocative works.

Oshima, who brought a unique perspective and aesthetics to Japanese cinema in the second half of the 20th century, is known as a director who dared to break and question society's taboos.

Born in 1932 in Kyoto, Japan, Nagisa Ōshima discovered his interest in literature and cinema at a young age. Although he studied law at Tokyo University, he preferred to improve himself in the field of art and culture. In the late 1950s, he became interested in the social and political issues of the younger generation in Japan, and his passion for cinema gradually increased during this period.

Nagisa Ōshima (March 31, 1932 – January 15, 2013) was a Japanese film director and screenwriter. One of the foremost directors within the Japanese New Wave, his films include In the Realm of the Senses (1976), a sexually explicit film set in 1930s Japan, and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), about World War II prisoners of war held by the Japanese.

Ōshima's career took off with the groundbreaking films he directed in the early 1960s. His films such as “Children of the Streets” (1959) and “Making Love” (1960) attracted attention and controversy by challenging the traditional norms of Japanese cinema. However, his real breakthrough came with films such as “A Woman Known for Her Passion” (1976) and “On the Wings of the Night” (1969). These films made a great impact in the cinema world with their striking stories based on sexuality, violence, and criticism of social norms.

Nagisa Ōshima played an important role not only as a cinema director but also as a screenwriter and producer. With his innovative perspective and bold themes, he pushed the boundaries of Japanese cinema and made it internationally known.

But Ōshima's career was not only full of success. His films often faced censorship and conservative backlash, and some were even banned. However, these obstacles encouraged Ōshima to pursue his art even more determinedly.

Today, Nagisa Ōshima's works are among the important works that have left their mark on the history of cinema not only in Japan but all over the world. His bold stance and provocative films provide an inspiring example of exploring the boundaries of art and sparking social change.

Ōshima passed away in 2013, but his legacy in cinema remains alive and continues to inspire future generations.

After 1959: Gangster Movie Variations

In the late 50s and early 60s, the Japanese cinema market was flooded with gangster films, reflecting the increasing criminality in major cities. Although some of Oshima's early films were considered to be in this genre, they differed from standard productions with their younger heroes and social/critical and political views. For example, in the movie Seishun Zankoku Monogatari (Cruel Tales of Youth, 1960), a university student from the proletariat class finds himself among criminals due to financial difficulties and pays with his life when he wants to return to regular life.

1960: The Ways of Politics

Oshima dared to undertake an ambitious project with Nihon no Yoru to Kiri (Night and Fog in Japan, 1960), which critically reflected on the Japanese student movement and its various ideological currents. Oshima had a falling out with the Shochiku company because of this film, which was withdrawn after being shown several times. Oshima henceforth worked as a freelance director and founded his own production company in 1965.

After 1968: Echoes in the West

In the mid-60s, Oshima began to display tremendous productivity. He made a name for himself as a radical critic of the latest historical developments and social norms. Meanwhile, he favored non-traditional forms of play and experimented with changing times and levels of subject matter, as well as with surprising distortions of reality (e.g. by showing a film within a film). He produced many films, but only a small portion of them reached the West. Europe began to notice Oshima only in the late 60s. He attracted the attention of Europe with his film Koşikei (Pull on a Rope, 1968). In this film, Oshima addressed the oppressed Korean minorities in Japan. Here, a Korean man named R. is sentenced to death for murder but loses his memory as a result of an unsuccessful execution attempt. Thereupon, the courthouse officers show the prisoner the crimes he has committed, first as a play and then seriously. With this film, Oshima was able to create an aesthetically bold kaleidoscope of different realities, as well as make a convincing accusation against the death penalty and the bureaucratic imperialist state.

Şonen (Little Boy, 1969) is an authentic examination of a lost childhood. In his film Gashiki (Ceremony, 1971), Oshima portrayed a patriarchal family held together only by religious holidays and behavioral patterns. With this film, he also presented a picture of Japan frozen in its traditions.

After the film Niatsu no Imoto (A Little Sister for the Summer, 1972), Oshima also fell victim to the crisis that Japanese cinema went into in the mid-70s. He was unable to work until 1976 and only worked for television.

1976: Scandal in Cinema History

While the film Shinjuku Dorobo Nikki (Diary of a Shinjuku Thief, 1969) showed that it was possible to overcome sexual dissatisfaction by taking a couple as an example, Ai no Corrida (Empire of the Senses, 1976), a Japanese-French co-production, highlighted the destructive aspect of sexuality. Here, based on an event that actually happened in the 30s, Oshima described the development of an increasingly enthusiastic love relationship, in which lust and the death drive gradually overlapped, and which ended with being castrated and strangled with a rope for the man. This film was considered a graphic work because the scenes were very explicit. This film, which was shown at the 1977 Berlin Cinema Festival, was seized by the prosecutor's office and was released only after the decision of the Federal Court. This was an official censorship event never seen before in the history of the International Film Festival.

After 1982: Withdrawal from the International Arena

Oshima barely appeared on the international stage starting from the 1980s. Furyo-Merry Christmas Mr., is about the argument between a British officer and a Japanese prison camp commander in World War II. Lawrence (Furyo-Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, 1982) was Oshima's last film to attract the attention of critics and audiences. After Max mon amour (Max My Love, 1986), Oshima shot a film about 100 years of Japanese cinema in 1994.