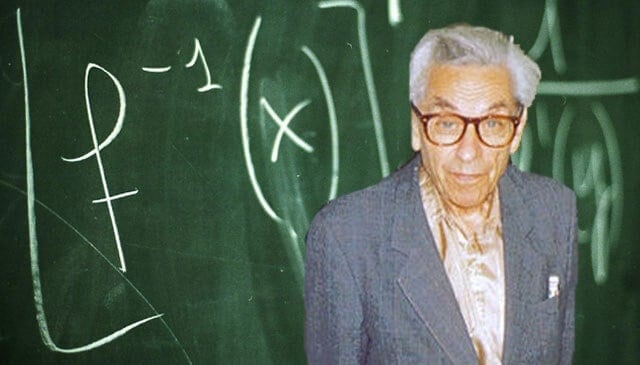

The great old man who turned coffee into a theorem: Who is Paul Erdös?

He built his life so that he could devote all the necessary time and energy to mathematics. He never married, did not develop any hobbies, and did not attach himself anywhere. He had neither a house nor a fixed place and kept all his belongings in a pair of suitcases.

How often do you say “How small is the world” when you realize that someone you just met on vacation is the neighbor of one of their best friends at school? In the 1960s, the American sociologist Stanley Milgram set out to investigate this issue. As a result, it is natural for people living in a small town to know each other. But is it really possible that two people who have nothing to do with each other are connected?

This work is known in the literature as "Small World Experiment and Six Degrees of Separation". Many other social interaction networks have also been analyzed since this classic experiment. One of them was about mathematicians.

As a result of this research, the name Paul Erdös emerged as the person who collaborated with other mathematicians the most in history. At the end of our article, we will explain the reason why it is called “Great Old Man”.

Paul Erdős (26 March 1913 – 20 September 1996) was a Hungarian mathematician. He was one of the most prolific mathematicians and producers of mathematical conjectures of the 20th century. Erdős pursued and proposed problems in discrete mathematics, graph theory, number theory, mathematical analysis, approximation theory, set theory, and probability theory.

Paul Erdös was born in 1913 in the glorious times of Budapest. Both of Erdös' parents were high school mathematics teachers. The family's original surname was Engländer. But, like many other Jewish families in Hungary, their surnames were to be changed.

The war and the following years were tough for the Erdös family. In 1915, his father was captured by the Russians and sent to Siberia. However, he was able to return after 6 years. Paul Erdös' mother would save her life but lose her job. In the end, Erdös became the only record of his mother and his mother was his only. This detail is important because this influence has affected his whole life.

As a child, Paul was immediately noted for his outstanding math skills. The problems of daily life were always taken care of by his mother. For this reason, Erdös could not even learn to tie his shoelaces throughout his life. But he has always loved to dive into deep mathematical discussions.

Erdös entered the University of Budapest in 1930 and received his doctorate in mathematics in 4 years. As a first-year student, he proved in a very simple way the theorem, which states that there is at least one prime number between the integers n and 2n, where n > 1. The world of mathematics heard the name of Paul Erdös for the first time with this proof. For Erdös, prime numbers were his faithful companions throughout his life.

Interesting Habits of Paul Erdös

Paul Erdös is a living legend not only for his ingenious solutions to dozens of problems related to number theory, graph theory, probability, combinatorial laws, and other themes but also for his extravagant lifestyle.

In 1938 he went to Princeton University, where he stayed for a year. Then he began to wander from one university to another. He turned down all of the full-time jobs offered to him. He was meeting with the mathematician of his choice and at his own time. His colleague, Bela Bollabas, noted for Erdös that "since 1934, it is rare that he slept in the same bed for seven consecutive nights."

He built his life so that he could devote all the necessary time and energy to mathematics. He never married, did not develop any hobbies, and did not attach himself anywhere. He had neither a house nor a fixed place and kept all his belongings in a pair of suitcases. Apart from eating, drinking, and sleeping for a few hours, there was no moment in his life that passed without math.

Erdös, who has always been in close relations with his mother, went on all his trips with his mother. And he always let his mother take full care of him. When this relationship ended with the death of his mother in 1971, Erdös was devastated and his eccentricities multiplied.

He gave most of his money to charities, especially young, penniless mathematicians. His response to his friends, who suggested that he rest a little, was always the same. “I will have a lot of time to rest in the grave…”. After all, "dying" for him meant giving up doing math.

In order to do more math, Paul Erdös worked 19 hours a day for the second half of his life, drinking copious amounts of strong espresso and caffeine tablets, which he called "the mathematician's drink." It is probable that he described the mathematician as "the machine that turns coffee into a theorem", and remains his most remembered phrase after him.

Contributions of Paul Erdös to Mathematics

In 1949, together with the mathematician Atle Selberg (1917–2007), Erdős proved the prime number theorem, which gives the approximation of the number of prime numbers less than or equal to any given positive. For this work and other discoveries in prime number theory, Erdős received the Cole Prize in 1951.

Over the next few decades, Erdős concentrated his studies on combinatorics, number theory, set theory, and geometry to illustrate the wide range of interests that dominated his life.

Poor Big Old Man

In 1970, at the age of 55, he began to write the letters PGOM at the end of his name. These are the initials of the phrase “Poor Great Old Man”. In his 60s, he adds LO (Living Dead) PGOMLD to it. On the 65th, he adds the letters AD to this abbreviation, transforming it into PGOMLDAD with Archaeological Discovery.

On the 75th he adds the letters CD to them. CD (Count Dead). The reason for this last addition is that the Hungarian Academy of Sciences no longer accepts members over the age of 75 as members, even if their rights remain.

Paul Erdős lived a full and apparently fulfilled life in his own way. He died on September 20, 1996, at the age of eighty-three, of a heart attack while attending a mathematics conference in Warsaw, Poland.