He became the head of the Cavendish Laboratory: Who is Prof Mete Atatüre?

Physics professor Mete Atatüre achieved great success as the head of Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory. Atatüre, who was deemed worthy of prestigious awards in his career, describes himself as "a teacher who does not assume that he is teaching" while talking about his adventure.

Prof Dr Mete Atatüre became the 16th head of the Cavendish Laboratory, known as the physics department of Cambridge University. The department announced the development on its social media account.

Mete Atatüre, born in Turkey in 1975, entered the top 500 in the university exam in Turkey in 1992. Atatüre graduated from the Department of Physics at Bilkent University, one of Turkey's important universities, and completed his doctorate in quantum physics. Atatüre, who started working at Cambridge University in 2007 and founded his own research group, worked in the same department of the same university with the famous physicist Stephan Hawking. Observing the noise measurement of light level, Mete Atatüre carried out dozens of studies in his laboratory.

Atatüre, who was awarded England's most prestigious award, the Thomas Young Medal, was deemed worthy of this award for making the noise measurement of the so-called immeasurable light level.

Mete Atatüre (b. February 19, 1975, Kayseri), is a Turkish physicist and academician. He is head of the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, also known as the Cavendish Laboratory. He works in the field of quantum physics. In 2015, Atatüre, who worked to better understand the nature of light, claimed on social media that he had carried out the 'noise measurement of light level', which is considered impossible to measure, but he denied this.

The questions we asked Atatüre and his answers are as follows:

How did you decide to become a physicist?

I was a child who oscillated between art and science, emotion and thought, under the influence of my parents. When I was 13, we went to America for my father's job. My secondary school physics teacher is the person who made me love physics. The books he gave me included not only physics problems, but also topics such as the Manhattan Project, where the first nuclear weapons of World War II were developed, and the life of Robert Oppenheimer, who was the head of the project and later fought against nuclear proliferation. I was interested in the fact that physical concepts had a story.

You are now a professor at Cambridge University. Why did you choose Cambridge?

England is a place that has common elements from the scientific research culture of America and Europe, so I have always been interested in it. However, there is a serious pyramid structure in academic career, so you cannot know in advance where you can find a position at which school in which country. I applied to a few schools. Cambridge's offer was more interesting, and I accepted it. Another factor is the quality of undergraduate and doctoral students.

What do you do off campus?

There is no time for many things, especially in the last two years. I watch movies whenever I get the chance, even during my sleep. I like listening to music, its type changes depending on my mood. Cycling and rowing are my favorite sports. I also have a cat, he has a special place.

So what kind of teacher are you?

A teacher who does not assume that he is teaching. The subject is not me, but the student. I am the guide. I like to engage students in the lesson by telling them about the place in the history of the topics we cover. For example, knowing under what conditions and at what times an equation emerged gives it more meaning.

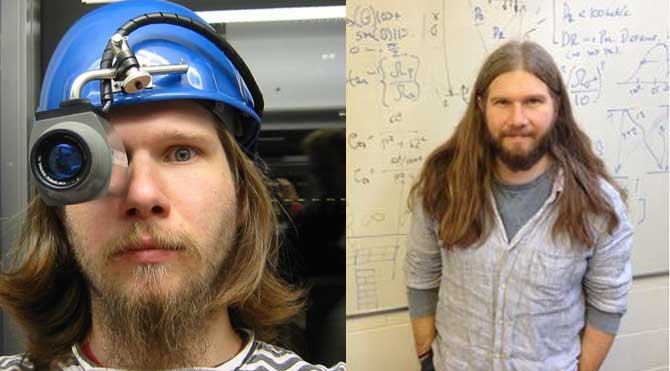

There are people in Turkey who find the length of your hair strange.

Because of stereotypes. During my high school and even university years, young people were subjected to violence because they had long hair or earrings, and they were not allowed on buses or minibusses. I've had my share of these, too. I guess it doesn't happen much anymore.

Have people gotten used to it?

Yes. We are in a period in science where the stereotype of the male, white, serious, and even old scientist is changing. Today, let's fight the battles we need to fight for the right to be different from the norm, including sexual orientation, and society will get used to all of them over time. That's why I'm hopeful about the future.