He argued that ideologies have lost their importance in industrialized societies: Who is Raymond Aron?

He opposed colonialism and demanded the withdrawal of French forces from Algeria. During the student events in May 1968, he harshly criticized the scientists who supported this movement.

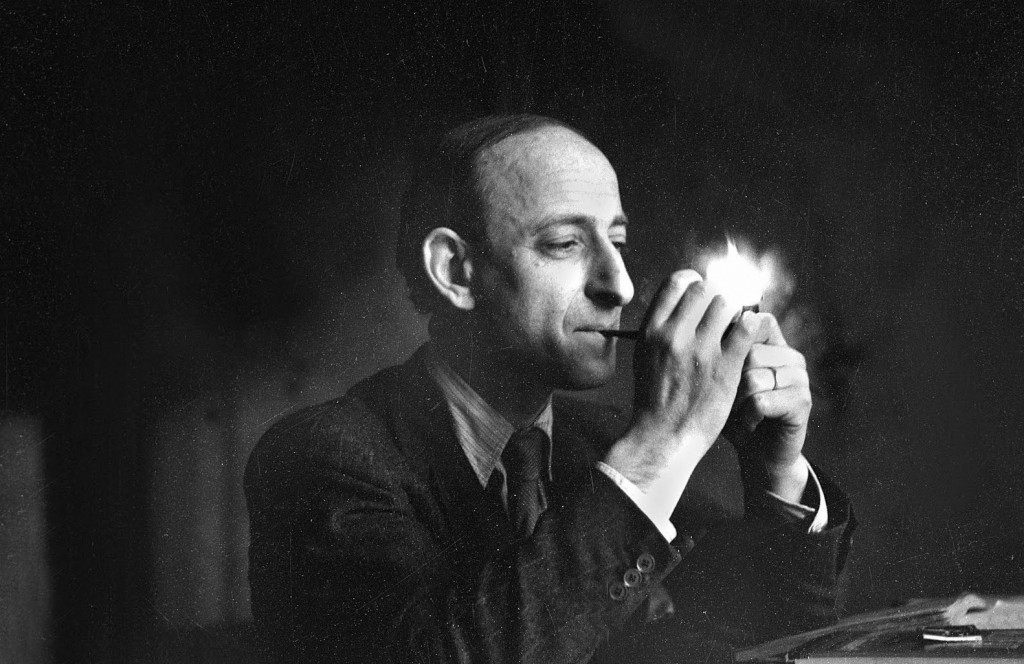

(1905-1983) French social scientist and journalist. He argued that ideologies lose their importance in industrialized societies. Raymond -Claude- Ferdinand Aron was born on March 14, 1905, in Paris, and died on October 17, 1983, in Paris. He received his doctorate from the Ecole Normale Supérieure in 1930. He taught at the University of Cologne and Le Havre High School until 1934. Between 1934 and 1939 he was the secretary of the Center for Social Studies at the Ecole Normale Supérieure. In 1939 he became a professor of social philosophy at the University of Toulouse. He served in the French Air Force during World War II; After the fall of Paris, he directed the newspaper La France Libre, the organ of the anti-fascist resistance movement led by Charles de Gaulle. He later co-founded Les Temps Modernes with Jean-Paul Sartre. After working for a while in the left-wing Combat magazine in 1946, he became the editor of the right-wing Le Figaro newspaper in 1947 and held this post until 1977. In 1955 he was appointed professor at Sorbonne University. He received the Legion d'honneur, Montaigne, Goethe, and Tocqueville awards. He was a lecturer at the College de France from 1981 until his death.

Aron, who was initially around left existentialists and especially Sartre, criticized the Western Marxists' support for the Soviet Union in his 1955 book L'Opium des intellectuelles (The Opium of the Intellectuals) and began to defend the US-led Western Alliance system. On the other hand, he opposed colonialism and demanded the withdrawal of French forces from Algeria. During the student events in May 1968, he harshly criticized the scientists who supported this movement.

In his essay Les Sociologues et les institutions representatives (“Sociologists and Institutions of Representation”), Aron argued that classical sociology did not give the necessary importance to political structures and criticized Marx, who tried to explain political forms of government with economic and social conditions. Influenced by Weber's views, Aron opposed the materialist interpretation of history and argued that each political structure can only be understood within itself. He did not deal with the manager-managed relationship at the historical-social level; evaluated this relationship as a phenomenon that has always existed and will exist throughout history. In the same work, Aron emphasized the autonomy of political government forms; He argued that the distinction between capitalist and socialist societies can only be explained by the difference in the political management styles of these societies.

In his work Democratie et totalitarisme (Democracy and Totalitarianism), which he wrote in 1965, Aron analyzed contemporary political systems by dividing them into two. The first group includes democratic or constitutional-pluralist systems, and the second group comprises totalitarian systems and one-party regimes. According to Aron, there is no people's self-government in constitutional-pluralist systems. Starting from the views of Pareto, Mosca, and Michels, who have an elitist approach, Aron claimed that every society is governed by a small number of people and that there is minority dominance even within the political parties. According to Aron, “The spirit of politics is that decisions are made for the community, not the community”. In democratic systems, pluralism means the reconciliation of all social forces through bargaining or coercion. Aron, who accepts the oligarchic character of the political regimes in Western societies as a given, is of the opinion that these are the systems that give the most assurance to the governed, and therefore should be defended. Aron defined totalitarianism, one of the political systems in the second group, based on the assumptions set by the US political scientists Brzezinski and Friedrich, and limited it to the 1934-1938 and 1948-1952 periods in the Soviet Union and the last years of the III Reich. He argued that one-party systems were mainly seen in the USSR and Eastern European countries. According to Aron, there are only implementation errors in the constitutional-pluralist systems in the West; On the other hand, the fault of one-party systems in socialist societies is intrinsic.

Aron argued that as industrial societies, capitalist and socialist countries face common problems. On the one hand, Western European economies are socializing and many industrial establishments are nationalized. Social security programs are implemented, and the state assumes responsibility to ensure full employment. On the other hand, the Soviet Union abandons the bureaucratic formalities restricting production and does not hesitate to adopt the economic methods in the West. In terms of politics, despite all the limitations of the system, it is moving towards the establishment of representative institutions. For this reason, ideologies are gradually losing their importance in the past; The conflict environment created by the ideological differences between the countries leaves its place to the solution of the common problems created by the industrial societies.

Aron, who was greatly influenced by elitist views, eventually became one of the advocates of "technocratic ideology". He adopted the distinction between democracy and totalitarianism, which is a product of the Cold War period in Western social sciences, and combined socialist systems and national socialist systems under the title of totalitarianism.

WORKS (mainly):

L'Opium des intellectuels, 1955, (The Opium of the Intellectuals);

Les Grandes doctrines de la sociolo-gie historiques, 1960, (Mainstreams in Sociological Thought);

Dixhuit leçons sur la societe industrielle, 1961, (Class Struggle: New Lessons on the Industrial Society);

Democratie et totalitarisme, 1965, (Democracy and Totalitarianism);

Essais sur les libertes, 1965, (“Essays on Freedoms”);

Trois Essais sur l'age industriel, 1966, (Industrial Society);

La Revolution introuvable: reflexions sur les evenements de mai, 1968, (“The Invisible Revolution: Reflections on the May Events”);

Etudes politiques, 1972, (“Political Studies”).