He was the human computer of the team that made the atomic bomb: Who is Richard Wesley Hamming?

Almost all of the scientists working on the Manhattan Project thought they were working to understand whether an atomic bomb could be made, but the real purpose was to determine whether firing the atomic bomb would cause combustion in the Earth's atmosphere.

Richard Wesley Hamming was born on February 11, 1915, in Chicago, Illinois, and grew up there. Although he wanted to study engineering, with the World Economic Depression occurring at that time, he went to the University of Chicago, which was the only place he could get a scholarship and did not have an engineering school and received his bachelor's degree in mathematics. (In his later statements, he considered it a good chance that he turned to the field of mathematics instead of engineering).

After receiving his master's degree from the University of Nebraska in 1939, he entered the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and received his doctorate in 1942 with his thesis titled "Some Problems in the Boundary Value Theory of Linear Differential Equation", which he wrote under the supervision of Waldemar Trjitzinsky, a mathematics professor. took.

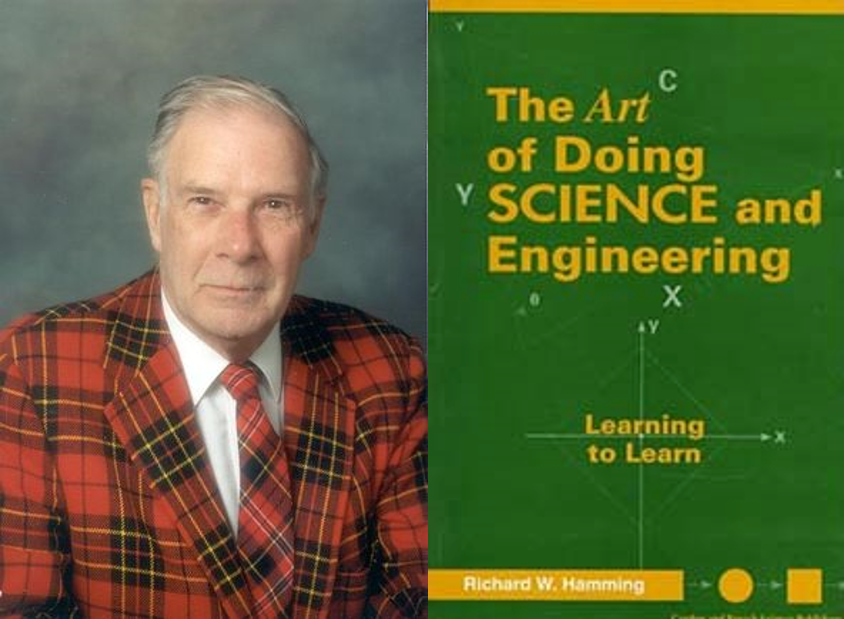

Richard Wesley Hamming (February 11, 1915 – January 7, 1998) was an American mathematician whose work had many implications for computer engineering and telecommunications. His contributions include the Hamming code (which makes use of a Hamming matrix), the Hamming window, Hamming numbers, sphere-packing (or Hamming bound), Hamming graph concepts, and the Hamming distance.

Trjitzinsky was interested in integrals, differential equations, analysis, and measure theory, and in 1936 he published a paper on linear differential systems limited to two specific points in Acta Mathematica, a journal that publishes research papers. Hamming's thesis was a more comprehensive study based on Trjitzinsky's article. Hamming especially worked on characteristic solutions for Green's functions and asymptotic expressions, which are used to specify a method used in mathematics to solve non-homogeneous differential equations under desired boundary conditions and the function calculated in relation to this method, and developed Jacob Tamarkin's methods to obtain characteristic solutions.

However, after reading George Boole's article "Laws of Thought" and interpreting it as interesting, useful, and reliable, his area of interest ceased to be differential equations. After receiving his doctorate in 1942, he married fellow student Wanda Little on September 5 of the same year and briefly worked as an instructor at the University of Illinois. Two years later, in 1944, he became an assistant professor at the University of Louisville.

While World War II was continuing, he left his job at the University of Illinois in April 1945 to work on the Manhattan Project, which was being carried out at Los Alamos Laboratories. (The Manhattan Project is a project initiated to produce nuclear weapons, with the scientific chairmanship of physicist Robert Oppenheimer and the military chairmanship of General Leslie R Groves, taking its name from Manhattan, where Columbia University is located, where the first research was conducted). As part of this project, Hamming programmed some of the first electronic digital computers to solve the equations put forward by physicists in Hans Bethe's department. A month after Hamming, his wife, Wanda, started working for Bethe and Edward Teller at Los Alamos as a human-computer (the name given to people who performed mathematical calculations when electronic computers were not accessible).

Almost all of the scientists working on the Manhattan Project thought they were working to understand whether an atomic bomb could be made, but the real purpose was to determine whether firing the atomic bomb would cause combustion in the Earth's atmosphere. As a result of the calculations, it was understood that no combustion would occur in the atmosphere, and the USA tested the bomb in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945, and then used it twice against Japan.

Hamming, who stayed at Los Alamos for another 6 months after the end of the Manhattan Project, wrote the details of his calculations. In 1946, he accepted an offer from Bell Telephone Laboratories in New Jersey and began working in the mathematics department there. Despite this, he maintained his relationship with Los Alamos, making 2-week visits every summer.

He worked with Claude Shannon, John Tukey, Donald Ling, and Brockway McMillan at Bell Laboratories. (After coming together, they called themselves Young Turks). Although his job there was to work on the theory of elasticity, he spent most of his time calculating machines. At that time, input errors were uploaded to readable punch cards, and when an error was found, a light would turn on for operators to notice and solve the error.

When operators were not present, the machine would move on to other operations. Hamming left the computer open over the weekend to make a calculation, and when he returned on Monday, he saw that nothing had been calculated because an error occurred in the first stages, he thought that the card reader was unreliable and that when an error occurred, it should be reported in which bit the error occurred, and thus a solution could be made. (Since computers work with a binary system, if the error bit is known, that bit can be converted to 0 if it is 1, to 1 if it is 0, and thus the error can be solved). Thereupon, he created a series of algorithms and in 1950 published the Hamming Code, which is known as a linear error-correcting code in telecommunications and can detect and correct single-bit errors.

Apart from these, Hamming worked on many areas during his time at Bell Laboratories, such as problems related to the design of telephone systems, the stability of complex communication systems, and blocking incoming calls through the telephone central office. He received the Turing Award in 1968.

Hamming, who worked at Bell Laboratories until 1976, died of a heart attack on January 7, 1998, one year after his retirement.