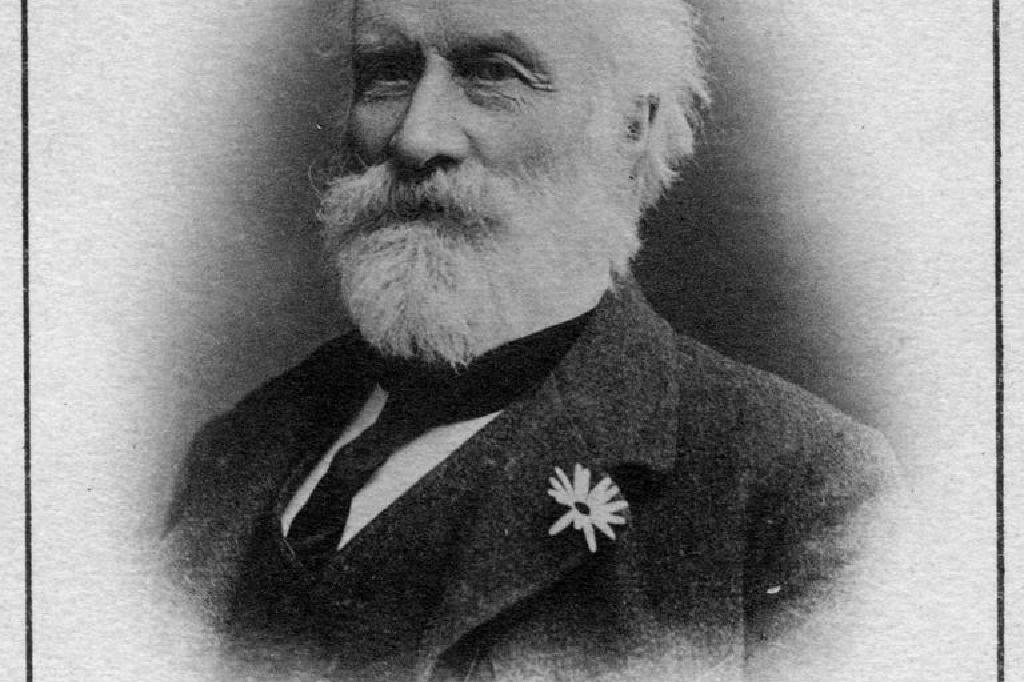

Engineer known as the inventor of time zones: Who is Sandford Fleming?

We have compiled the adventure from past to present of Sandford Fleming, who pioneered a great development by finding the standard time system after he missed a train due to the confusion in the clocks, as well as an engineer for the railways.

Sir Sandford Fleming was born on January 7, 1827, in Kirkcaldy, Fife, Scotland. He was born the son of his father, Andrew Greg Fleming, and his mother, Elizabeth Arnold Fleming. Fleming has an older brother named David. Beginning an apprenticeship as a cartographer at the age of 14, Fleminf emigrated to Canada in 1845 with his older brother David. The duo, who lived in many cities of Canada, settled in Peterborough with their cousins two years later.

After moving to Peterborough, Fleming became friends with the family of his wife-to-be Halls, and became interested in Ann Jane (Jeanie) Hall. But the couple's love for each other wasn't revealed until a sledding accident ten years later. In 1855, a year after its appearance, Sandford married Sheriff James Hall's daughter, Ann Jane (Jean) Hall. The couple had a total of nine children, two of whom died. The family man, Fleming's family, who was deeply attached to his wife and children, was also in frequent contact with his wife's family.

In 1849, Fleming, along with a few of his friends, founded the nonprofit "Royal Canadian Institute", which was formally established on November 4, 1851. Originally conceived as a professional institute for surveyors and engineers, the organization has grown into a more general scientific community. In 1851, he designed the "Threepenny Beaver", the first Canadian postage stamp for the Province of Canada. During this time he was hired as a surveyor for the Grand Trunk Railroad, and in 1855, his studies eventually earned him the position of Chief Engineer of the Canadian Northern Railroad. While in this position, he advocated the construction of iron bridges instead of wood for safety reasons.

During his time on the railroad, he continued in opposition with the architect Frederick William Cumberland, with whom he co-founded the Canadian Institute and was the railroad's general manager until 1855. Fleming, who started as an assistant engineer on the highway in 1852, succeeded Cumberland in 1855, but was overthrown by Cumberland in 1862.

Fleming served in Canada's 10th Battalion Volunteer Rifles (later known as the Royal Canadian Regiment). He was appointed to the rank of captain on January 1, 1862, and retired from the militia in 1865. In the sequel to 1862, he advanced to the government a plan for a transcontinental railroad linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. The first partition between the Halifax and Quebec regions was spoken of, with the uncertainty of traveling through Maine due to the American Civil War becoming an important part of the preconditions for New Brunswick and Nova Scotia to join the Canadian Federation.

In 1863, tasked with building a line from Truro to Pictou, Fleming took a position as Nova Scotia's chief government surveyor. Flmeing, who did not accept the proposals from the contractors for this line, which he found too high, offered the job himself and was able to complete the line in 1867 with both government savings and profit for himself. In the same year, he was appointed as the chief engineer of the "Intercolonial Railway", which became a federal project, and continued in this position until 1876.

Around this time, by 1871, Fleming was offered the post of chief engineer on the Canadian Pacific Railroad, using a rail link strategy to bring British Columbia into federation. Accepting the offer, Fleming set out in 1872 with a small group to specifically explore the route through the Rocky Mountains and found a practical mountain pass route through Yellowhead Pass. One of his companions, George Monro Grant, wrote a best-selling story of their trip.

In June 1880, Fleming was removed from his post on a payment made by Sir Charles Tupper, who was serving as Canada's prime minister. Having received the hardest blow of his life, Fleming took up the post of Chancellor of Queen's University in Ontario. He continued this duty in his last 35 years as director until 1902.

Known for "the first effort that led to the adoption of the present meridians," Fleming missed a train while traveling in Ireland in 1876. As a result, he proposed a single 24-hour clock for the entire world, which is conceptually at the center of the Earth and is not connected to any surface meridian. He later named this time "Cosmopolitan time" and later "Cosmic Time". In 1876, Felming wrote a memoir, "Terrestrial Time," in which he proposed 24 time zones, each one hour wide or 15 degrees longitude. The regions are labeled AY except J and connected to the "Greenwich" meridian, designated G. All times in each region would be set to the same time as the others, and alphabetic labels could be used as common notation across regions. For example, when the cosmopolitan time was G:45, it would show 14:45 local time in one region and 15:45 in the next region.

In two articles, "Calculation of Time" and "Calculation of Longitude and Time," presented by the Canadian Institute at a meeting in Toronto in February 1879, Fleming revised his system to connect with the anti-meridian of Greenwich. Suggesting the selection of a prime meridian, Fleming analyzed shipping numbers to suggest Greenwich as the meridian. These two articles of Fleming became so important that in June 1879, copies were sent to eighteen foreign countries and various scientific institutions in England. An intellectual, Fleming wrote a book on HBC's land policy in 1882. In the same year, keeping up with business ventures, Fleming became one of the founders of "Nova Scotia Cotton Manufacturing Company" in Halifax.

Fleming continued to defend his system at many major international conferences. In 1884, he began working as director of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, where he was on duty as the last increase was driven. The International Meridian Conference, along with the "Greenwich Meridian", adopted a universal 24-hour day starting at midnight Greenwich. In 1886, Fleming discussed the pamphlet "Time Calculation for the 20th Century" published by the Smithsonian Institution.

In 1880, serving as vice-president of the Ottawa Horticultural Society, Fleming left the Ottawa Curling Club in 1888 to protest its policy of moderation and took over as the first president of the Rideau Curling Club. Turning his attention to electoral reform and the need for proportional representation in the early 1890s, Fleming wrote two books on the subject, "An Appeal to the Canadian Institute for the Adjustment of Parliament" (1892) and "Essays on the Adjustment of Parliament" (1893). Later, he wrote the book "Canadian and British Imperial Cables".

Well-known worldwide for his achievements, Fleming was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1897. In 1906, the modern "Canadian Alpine Club" was formed in Winnipeg, and by that time Fleming was the club's first boss and president. Retiring from his Halifax home in his later years, Fleming later transferred his home and 95 acres (38 hectares) of land to the city now known as "Sir Sandford Fleming Park" (Dingle Park). Fleming, who also has one more home in Ottawa, was buried in Beechwood Cemetery after his death on July 22, 1915.

In 1929, all major countries in the world adopted time zones. Today, the UTC offset divides the world into zones, and military time zones assign letters to 24-hour zones, similar to Fleming's system. In addition, Fleming designed the first Canadian stamp in 1851, a three-cent stamp with the Canadian national animal "The Beaver". Fleming was recognized as a "National Historic Person" in 1950 upon the decision of the national Board of Historic Places and Monuments. On January 7, 2017, Google celebrated Fleming's 190th birthday with a "Google Doodle".