He became the first American writer to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1930: Who is Sinclair Lewis?

Lewis thinks that most Americans generally speak according to expected norms, behave as they are expected to, and are conventional about individuality and originality.

As you read Babbitt, you constantly feel Sinclair Lewis' anger at the mediocrity of America. Lewis thinks that most Americans generally speak according to expected norms, behave as they are expected to, and are conventional about individuality and originality. The characters he describes live in the cliché-filled days of the 1920s, as if stuck in a colorful cookie cutter. Ironically, Lewis's own childhood also fits these stereotypes. It is difficult to accept that Lewis's life conformed to the typical pattern almost necessary for creative talent.

Harry Sinclair Lewis was born in 1855 in the small town of Sauk Centre, Minnesota. He grew up in a disciplined home and was instilled with a sense of responsibility and seriousness at an early age by his father, a doctor. His two older brothers followed their father's profession and became doctors, but Lewis did not want to fit that mold. He attracted attention as a creative child at an early age. Red-haired, introverted, and fond of reading, Lewis also started writing at the age of 11.

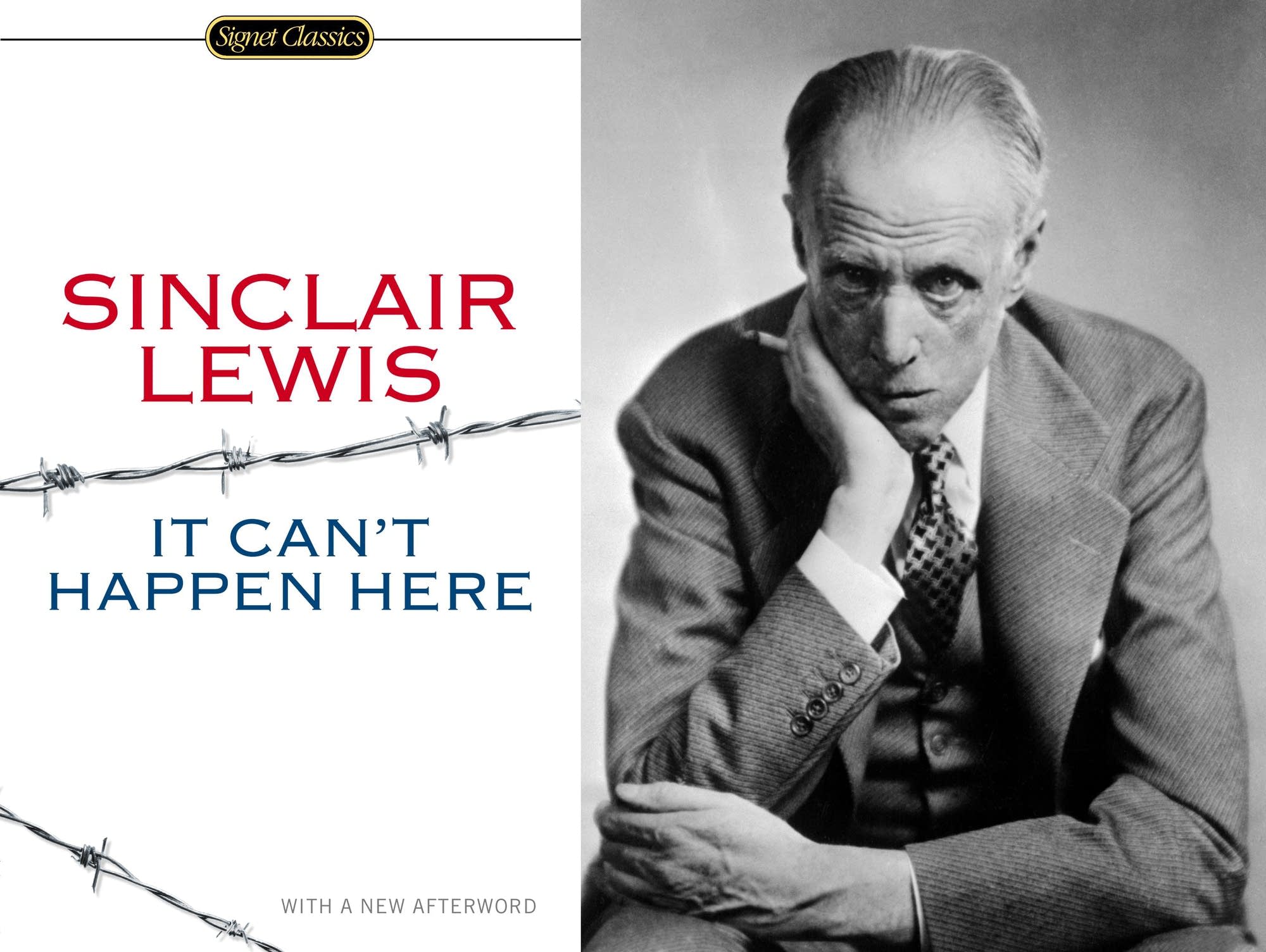

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. In 1930, he became the first author from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was awarded "for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters." Lewis wrote six popular novels: Main Street (1920), Babbitt (1922), Arrowsmith (1925), Elmer Gantry (1927), Dodsworth (1929), and It Can't Happen Here (1935).

In his last years of high school, he worked alternately at two newspapers during the summer months and attempted to publish poetry. He continued writing at Yale University, but he had few friends other than English majors who encouraged him in his literary pursuits. After his first year, he temporarily abandoned his studies and went to England. When he returned to Yale, he regained his passion for writing; He continued to write essays, poems, and short stories. He traveled for a time in Europe, stayed in Upton Sinclair's socialist community, tried freelance writing, and went to Panama. Finally, he returned to Yale in June 1908, finishing his two-term study in just over one semester and receiving his degree.

After Our Mr Wrenn, he published four more novels, all of which reflected what it meant to be "American." In these early books, Lewis addressed the fate of the American spirit that had led and reinvented a nation but now had no frontiers to conquer. He underlined this problem by trying techniques such as exaggeration and irony. Yet, despite his research on America, he remained largely unknown.

He became a well-known writer with his novel Main Street in 1920. His novel offered a bold critique of the romanticized myth of small towns and reflected Lewis's deep feelings about the sincerity and honesty of small towns growing up. Main Street had a huge impact across America, and Lewis became a controversial figure among the press and the public.

Two years later, he surprised America once again with his work Babbitt. This time, he painted a portrait of a bourgeois who was internally unsatisfied despite achieving success and wealth. Over time, Babbitt became one of the classics of American literature, and the word "Babbitt" managed to take its place in American dictionaries. The word is still used today to describe people who strictly adhere to social norms and achieve a respectable middle-class lifestyle, but have limited social awareness and imagination.

Lewis continued to write works criticizing American society from various aspects at different periods of his career. He first attracted attention by satirizing small towns and suburban life with works such as Main Street and Babbitt. Later, he discussed the medical world in Arrowsmith, religious quackery in Elmer Gantry, and Europeanism versus Americanism in Dodsworth. In 1930 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for all his works, but this award came at the peak of his career.

After the award, Lewis's works lost their former influence. His works, such as Ann Vickers, Cass Timberlane, and Kingsblood Royal, achieved financial success, but critics felt that these novels were overshadowed by the masterpieces he wrote before the Nobel Prize. Perhaps his most important work that broke this equation came in 1935. He received praise again for his political dystopia based on alternative history, It Can't Happen Here. The New Yorker evaluated the work as "not only Lewis's most important book but one of the most important books ever written in this country."

Despite everything, Lewis began to lose his professional reputation, although he still continued to cover controversial topics in his writings. He remained overshadowed by other American writers and struggled with alcohol problems. After their unsuccessful marriage, he died alone in Rome in 1951. His last work, World So Wide, was published posthumously. Lewis made significant contributions to the literary world with his works that questioned and criticized American society, but he could not demonstrate the same success in dealing with his personal difficulties.