Who is the hominin and how did they eat in the past?

The terms "hominin" or "hominid" usually refer to australopithecines. Australopithecines have the ability to stand on two legs and their skull structure is similar to that of Homo species (or humans). Their brains are quite small compared to Homo species.

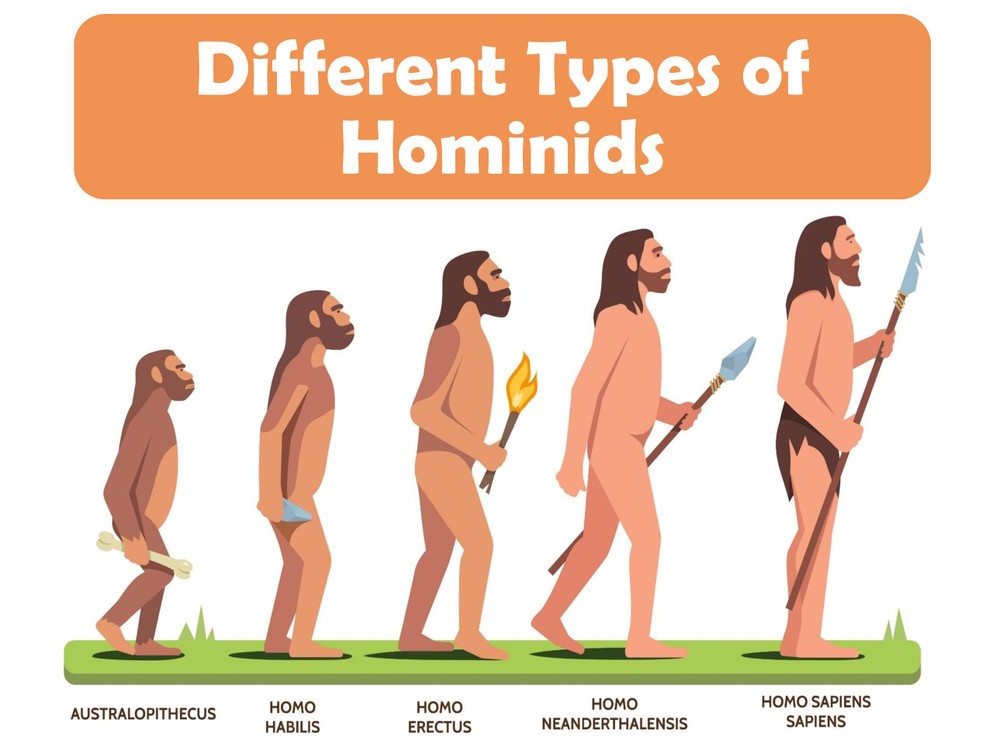

Evolution of Hominids: Hominoidea, Hominidae, Homininae, Hominini, Hominina and Homo (sapiens)

The word "human" is used differently in science than it is used among the public. Human is a word often used to describe the animal genus called Homo. But we "anatomically modern humans" (scientifically known as Homo sapiens) are not the only species of Homo. To date, around 14 different species have been described under the genus Homo. All of these are extinct. However, for example, the human species called Homo neanderthalensis, popularly known as Neanderthals was among us only 30,000 years ago! Similarly, another human species, the Flores Humans (scientifically known as Homo floresiensis), lived on Earth alongside us modern humans until just 13,000 years ago! Although this is inconceivable, it is real. "Human" is not the only human species that has ever existed. It probably won't be the last.

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera Homo (humans) and Pan (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus Gorilla (gorillas). The term was originally introduced by Camille Arambourg (1948). Arambourg combined the categories of Hominina and Simiina due to Gray (1825) into his new subtribe.

Scientists have constructed a pyramid of taxonomic groups around the genus Homo. For example, Hominids, which we can translate into Turkish as "humanoid", is the common name of all our ancestors and cousins who lived in the last 6 million years, when we diverged from the evolutionary family tree that will come to us modern humans, including our common ancestor with chimpanzees, which will lead to our closest living cousins, chimpanzees.

A human is a species of hominid (species of humanoid).

How did hominids eat?

The hominin group, which includes humans and our extinct relatives, may have competed with giant hyenas for carcasses abandoned by saber-toothed cats and jaguars during the late Pleistocene period in southern Europe, about 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago.

Findings from a modeling study published in Scientific Reports suggest that medium-sized hominin groups may be the most successful at scavenging.

In biology, a tribe is a taxonomic rank above genus, but below family and subfamily. It is sometimes subdivided into subtribes. By convention, all taxonomic ranks from genus upwards are capitalized, including both tribe and subtribe. Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

Previous research has suggested that the number of carcasses abandoned by saber-toothed cats may have enabled the early hominin populations in Southern Europe to survive. However, it remained unclear whether other large scavengers, such as giant hyenas, limited hominin access to this food source.

Ana Mateos, Jesus Rodriguez, and colleagues ran simulations to model carrion competition between hominins and giant hyenas (Pachycrocuta brevirostris) on the Iberian Peninsula during the late-early Pleistocene.

The researchers simulated whether saber-toothed cats Homotherium latidens and Megantereon white and the European jaguar Panthera gombaszoegensis could leave enough carrion to support hyena and hominin populations, and how this might have been affected by the size of scavenger hominin groups.

The authors found that when hominins gathered in groups large enough to chase giant hyenas (five or more individuals), hominin populations exceeded giant hyena populations by the end of the simulations. However, when hominins were scavengers in very small groups, they were only able to survive until the end of the simulation, when predator density and therefore carrion availability was high.

The simulations also suggested a potential optimum group size for scavenger hominins. Groups of more than 10 individuals could chase saber-toothed cats or jaguars, while groups of more than 13 individuals needed more carrion to sustain their energy expenditure. However, the authors note that their simulations were unable to determine what the optimal group size was because the number of hominins needed to chase away hyenas, saber-toothed cats, and jaguars was predetermined and arbitrarily assigned.

The findings suggest that medium-sized late-to-early Pleistocene hominin groups in Southern Europe were able to regularly obtain food by scavenging, even when in competition with giant hyenas. The authors think that the collected remains could have been an important source of meat and fat for hominins, especially during the winter months when plant resources were scarce.