A life story that will be the subject of movies: Who is Walter Pitts?

Walter was a different kid. He was an autodidact who learned many languages, including Latin and Greek, as well as logic and mathematics on his own.

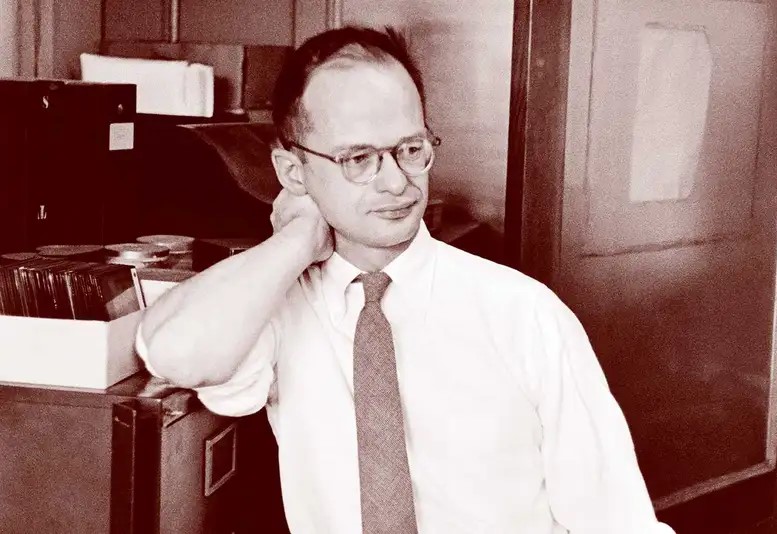

Walter Pitts was born on April 23, 1923, in Detroit, Michigan. Needless to say, he was not a very lucky boy. He had a childhood full of bullying by his family and friends in the neighborhood. But Walter was a different kid. He was an autodidact who learned many languages, including Latin and Greek, as well as logic and mathematics on his own.

Walter Harry Pitts, Jr. (23 April 1923 – 14 May 1969) was an American logician who worked in the field of computational neuroscience. He proposed landmark theoretical formulations of neural activity and generative processes that influenced diverse fields such as cognitive sciences and psychology, philosophy, neurosciences, computer science, artificial neural networks, cybernetics and artificial intelligence, together with what has come to be known as the generative sciences.

One afternoon in 1935, the neighborhood kids started chasing Walter. He too found the cure by hiding in the city library, a familiar and safe place for him. For Walter, who was only 12 at the time, the library was different from the outside. When he entered the library, his father, who had forced him to quit school and start a job, his abusive siblings, and the children in the neighborhood disappeared. The outside world was in chaos; order and logic in the library.

Not wanting to risk another chase that day, Walter stayed there until you were locked up in your library. He wandered around the library until evening, until he came across Russell and Whitehead's Principia Mathematica.

This book was a treasure to Walter, so he immediately sat down and started reading. He carefully read this book of nearly 2000 pages for three days. He even found a few mistakes and wrote a letter and sent it to Russell. Russell was so impressed when he read the letter that he invited Walter to work as a graduate student at Cambridge. Walter did not accept the offer but had already decided to become a logician.

Three years later, Walter received the news that Russell was coming to the University of Chicago. He then ran away from home to Illinois and never saw his family again. Although he was not an enrolled student at the University of Chicago, he attended Russell's lectures there. He met Jerome Lettvin, a medical student, in 1938 and they became close friends. Russell, a visiting professor at the University of Chicago, introduced Pitts to the logician Rudolf Carnap.

Continuing to work with Carnap, Walter Pitts also attended theoretical biology seminars with Gerhardt von Bonin. In 1940, von Bonin introduced Pitts' friend Lettvin to Warren McCulloch. Pitts also met McCulloh on this occasion.

When Pitts was born in 1923, McCulloh was trying to digest Principia Mathematica. McCulloh, unlike Pitts, was brought up in a highly intellectual environment. He studied mathematics at Haverford College and philosophy and psychology at Yale University. He was about to receive his medical degree in neurophysiology in 1923. But McCulloh was essentially a philosopher.

Warren Sturgis McCulloch (November 16, 1898 – September 24, 1969) was an American neurophysiologist and cyberneticist known for his work on the foundations of certain brain theories and his contribution to the cybernetic movement. He wanted to know what it meant to know. At that time, Freud had just published Ego and the Id, and psychoanalysis was in vogue. McCulloch hadn't paid much attention to the Ego and the Id. He was somehow certain that the mysteries of the mind were due to the purely mechanical firing of neurons in the brain.

These two names, who had traveled very different paths, looked too strange to be a team when they came together. McCulloh was a confident philosopher-poet who lived on booze and ice cream, never going to bed before 4 a.m. Walter Pitts was just 18, a shy, bespectacled, homeless fugitive. But they had one thing in common that brought the two together: Gottfried Leibniz. Leibniz, one of the important philosophers and mathematicians of the 17th century, tried to create a human thought that could be manipulated and had a set of logical rules for calculating all information, with each letter representing a concept.

McCulloh wanted to model the brain with a Leibnizian logical computation. He was inspired by Principia Mathematica, where Russell and Whitehead tried to show that all mathematics could be built from scratch using basic, indisputable logic. The building block Russell and Whitehead used in doing this was the proposition.

The smallest stimulus that generates an action potential in a neuron is called the threshold. The neuron does not respond to stimuli lower than the threshold value. It responds with the same intensity to stimuli at and above the threshold value. This is called the all-or-nothing principle.

McCulloh knew that neurons fire when they pass a certain minimum threshold. It occurred to me that this situation is binary. That is, neurons would either fire or not fire when a stimulus came. Neurons actually worked like logic gates, taking multiple inputs and producing a single output. The warning represented propositions. Then, by changing the firing threshold of a neuron, it could be made to perform functions such as "and", "or", "or not".

McCulloh had read Alan Turing's article On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Talking about a virtual machine based on theoretical and mathematical foundations in his article, Turing claimed that all kinds of mathematical calculations can be done with this virtual machine. According to McCulloh, the brain was just such a machine. Like the chains of propositions linked together in the Principia, neurons could be linked by logical rules to form more complex chains of thought.

McCulloh was quick to explain this project to Pitts. And luckily, Pitts knew what mathematical tools could be used. The friendship between the two was also very good. So McCulloch invited Pitts to live with him and his family in Hinsdale, a rural suburb of Chicago. McCulloh and Pitts worked on their project until late at night after everyone in the house had gone to bed.

Pitts, who started the studies, noticed something. Although our genetics should determine some of our neural traits, there was no way our genes could predetermine the trillions of synaptic connections in our brains. So we were all born with random neural networks. Therefore, he began to suspect that randomness could lead to order. He then decided to do modeling using statistical mechanics. This situation pleased Wiener very much. Because if the model was successful on a machine, machines could learn.

That winter, Wiener invited Pitts to a conference he held at Princeton. He introduced him to the mathematician and physicist John von Neumann. Thus, the cybernetics group was formed. The core of the group consisted of Wiener, Pitts, McCulloch, Lettvin, and von Neumann.

Standing out from among the group, like this parade of stars, was, of course, Walter Pitts. But for each of the band members, Pitts was very important. “None of us would ever consider writing an article without his corrections and approval,” McCulloh said. Lettvin said, “When you ask him a question, you get a textbook full of information. To him, the world was very complex but wonderfully interconnected,” he said.