The boss of the political mafia that once ruled New York: Who is William Tweed?

Boss Tweed was a famous figure who dominated New York in the mid-1800s and controlled the Democratic Party in New York state throughout his years in power. He is often cited as an iconic figure of corruption and ruthlessness.

The prison sentence given to him marked a critical turning point in New York politics.

William Tweed, one-time dictator of New York, was born in 1823, the son of a chair maker. He worked as a saddlemaker's apprentice during his childhood. He studied accounting. He became a firefighter in his mid-20s. Those were the days when fire companies, each affiliated with a different group or gang, were in fierce competition. So much so that sometimes two fire companies arriving at the scene of the fire would get into a fight, and in the meantime, the building that was still burning would turn to ashes. Besides the gangs, each political faction had its own Fire Company. It didn't take long for Tweed's ambition and talents to attract the attention of politicians. In 1851, at the age of 27, he managed to be elected as a member of the city's municipal council. This is how one of the most legendary corruption stories in the history of politics and media began.

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party's political machine that played a major role in the politics of 19th-century New York City and state. At the height of his influence, Tweed was the third-largest landowner in New York City, a director of the Erie Railroad, a director of the Tenth National Bank, a director of the New-York Printing Company, the proprietor of the Metropolitan Hotel, a significant stockholder in iron mines and gas companies, a board member of the Harlem Gas Light Company, a board member of the Third Avenue Railway Company, a board member of the Brooklyn Bridge Company, and the president of the Guardian Savings Bank.

Tweed saw very well how quickly New York was beginning to change with waves of immigration and new industries, and he threw his surfboard into the rising tide. In the early 1850s, he managed to become a member of the political chamber called Tammany Hall, which dominated city politics. The Tammany community took its name from the legendary Native American chief 'Tamanend'. They called the group leader "sachem" (which means tribal leader in Native American) and their building "wigwam" (tent). William Tweed was elected chairman of the New York region Democratic Party in 1860 and was elected 'Grand Sachem' of the Tammany community in 1863. He was now the most powerful name in the city.

Gold-plated misery and Robber Barons

While the North-South Civil War condemned the American people to great poverty, the new industries formed after the war caused the emergence of a new rich class in the USA. The powerful figures of this period, who became rich using politics and newspapers, are called 'Robber Barons' in the US political literature. The term was first used in the August 1870 issue of Atlantic magazine. Around 20 businessmen, from railway magnate C Vanderbilt to oil giant J D Rockefeller, from the father of finance J P Morgan to tobacco tycoon JB Duke, from steel tycoon A Carnegie to real estate giant Jacob Astor, who became rich rapidly in the period lasting until the 1890s. He is among the leading names of the 'Harami Barons'. This era of corruption, in which politicians could also own companies, participated in this race for wealth through land speculation and financial manipulations, and newspapers acted as their hitmen, is today called the 'Gilded Age' because of Mark Twain's novel of the same name, published in 1873. In his novel, Twain describes in a satirical manner the great social and economic misery and decay beneath the gold-plated image.

Because Tweed rose from the bottom to the top of this social structure, he knew very well how to gather power into his hands. He never neglected to give his supporters a share of what he earned. His name was now 'Boss Tweed'. When 'Boss' was mentioned in the city, everyone knew who was meant. As the once poor Tweed entered the 1870s, the famous '5th. He now lived in a magnificent mansion on the Avenue. Behind the scenes of the political organization, he was running the organized crime group known today as the 'Tweed Ring'. New York Mayor Oakey Hall, Public Projects Department Head Peter Sweeny, who managed all tenders in the city, and city comptroller Richard Connolly, who was responsible for supervising all of these, were his assistants. In 1869, he had his own man elected governor of New York state. By bribing Republican members of the State Congress with $600 thousand, he renewed the New York City Constitution and brought the city to elections. Now all 15 members of the city's new council were men of the Tweed gang. He has control over everything, from state politics to the city's municipal politics to the New York media.

Luc Sante, in his book 'Low Life', tells strikingly how Tweed brought famous swindlers to the top administrative positions of the city in those days, and how convicted thieves were appointed as officials in the courts. For example, trickster Tim Donovan became assistant manager of Fulton Market, the commercial heart of the city; comedian 'Oofty Goofty' Phillips became Water Board administrator, and thug Jim 'Maneater' Cusick was appointed courthouse officer. An open market was also established to bribe anyone who was sued. Everyone guilty of paying Tweed's price was free from prosecution. It was Tweed again who brought judgment upon them. (Low Life, page 263)

While Tweed was running the city, he also became the boss of the Erie Railroad Company, the Brooklyn Bridge Company, the Third Avenue Railroad Company, and the Harlem Gas Oil Company, which made the largest investments of the period. He was president of Guardian Savings Bank and owner of Tenth National Bank. He largely invested the money he earned from bribes into real estate. He was New York's largest landowner in the early 1870s. He was buying worthless lands outside the residential areas of that day, building roads in the region with the municipality's means, increasing the value of the land, and selling it. The famous Harlem district is also a product of this period.

He established his order thanks to immigrants

These were the years when the first mass migration from the Old World to the New World began. These immigrants were the most important human resources of Tweed's political gang order. Especially Irish immigrants. The fact that they were constantly despised and ostracized by the Protestant natives, who saw themselves as 'real Americans', was the most important factor in the Catholics' pursuit of William Tweed. Thanks to them, he was able to manipulate every election in the city as he wanted. Even today, Tweed's influence is great in the fact that the New York police department, NYPD, and the Fire Department, NYFD, are mostly in the hands of people of Irish origin. In his famous biography, "Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of a Corrupt Politician," Kenneth Ackerman writes:

"Tweed respected the despised immigrants as 'voters'. He won the respect and loyalty of these immigrants through unprecedented municipal and public welfare programs. He provided aid in different ways. He also provided money from the state budget to build schools and hospitals in immigrant neighborhoods. He also delivered coal to immigrants' homes at Christmastime. Or, they were subcontracting public works that could help them earn a living. "Tweed was giving a sense of his own power and belonging to immigrants who had come to a new continent, were trying to build a new life, and were also subjected to the pressures of the native majority."

On election days, Catholic immigrants flocked to the polls. Some were voting 10 or even 20 times. They were not ashamed of the repeated vote fraud. On the contrary, they were telling it everywhere. This was the only way to become a member of the Democratic Party that ruled the city, for some to get a job in city government, for many to earn a living, and for all to become an American. Never before seen rally crowds were gathering in squares such as Union Square. Many saw Tweed as something of a Robin Hood. In his book, Kenneth Ackerman describes Tweed as a "cross-eyed Robin Hood":

“This Robin Hood takes for himself a third of what he steals from the rich. He divides one-third among the leaders and members of the gang. He gives 5 percent to newspapers in Sherwood Forest. After all this, he spent the remaining money on the poor. "That's the kind of Robin Hood Tweed was."

As Tweed saw the size of the commissions and rent he was getting from public projects, he initiated much larger public projects. The source of all these investments was borrowing. New York's debt increased from $30 million to $100 million in that day's currency just between 1868 and 1870. It would be determined that the Tweed gang stole more than $8 billion from the public in 2009. Kenneth Ackerman describes how Tweed's system, which he describes as 'the hero of the biggest local government corruption in history', works in tenders as follows:

“If you wanted to sell any goods or services to the city government, you submitted your invoice to the City Board. Tweed was taking 15 percent of your profits through his men on this board. However, over time, this rate increased to 25, 35, 45 percent, and even up to 65 percent at one point.

Ironically, Tweed's biggest public investment fraud was a courthouse. The building, which had a construction budget of 250 thousand dollars when it started in 1858, resulted in a total of 13 million dollars from the municipal budget (178 million dollars in today's money) when it was completed. This amount of money paid for the construction of a single building was more than twice the amount paid by the United States to the Russians to purchase Alaska in 1867. It was recorded as the most expensive building of the 19th century.

He established his own media

In the early days when the city began to become the center of power, Tweed saw newspapers as "the primary power that must be kept under control." Every item he couldn't buy was a threat to him. Rodger Streitmatter, in his book 'How the News Media Shaped American History', describes the media landscape of that day as follows:

"In 1862, the New York legislature passed a bill to pay each reporter $200 a year for 'service to the city.' With the 'generosity' of Tammany Hall, this amount increased 10-fold in a few years. However, what established the administration's influence on the media was the city's advertising budget, rather than this salary. Tweed was placing $80,000 a year in public advertising in each of the city's three largest newspapers, the New York World, the New York Herald, and the New York Post. During Tweed's empire of corruption, the sum of money sent from the city treasury to the newspapers to gain their silence was $7 million at the time.

Tweed dominated the media with his money and the entire agenda of New York with his media. Until all this glamorous show hit the pen of a low-circulation intellectual newspaper and a cartoonist...

That all changed when two officials angry with Tweed leaked spending documents to the New York Times, alleging corruption in this courthouse construction and other municipal expenditures. The first news was published on July 8, 1871. The Tweed gang ignored it at first. They still believed they could cover it up. But they had not calculated the power of a cartoonist.

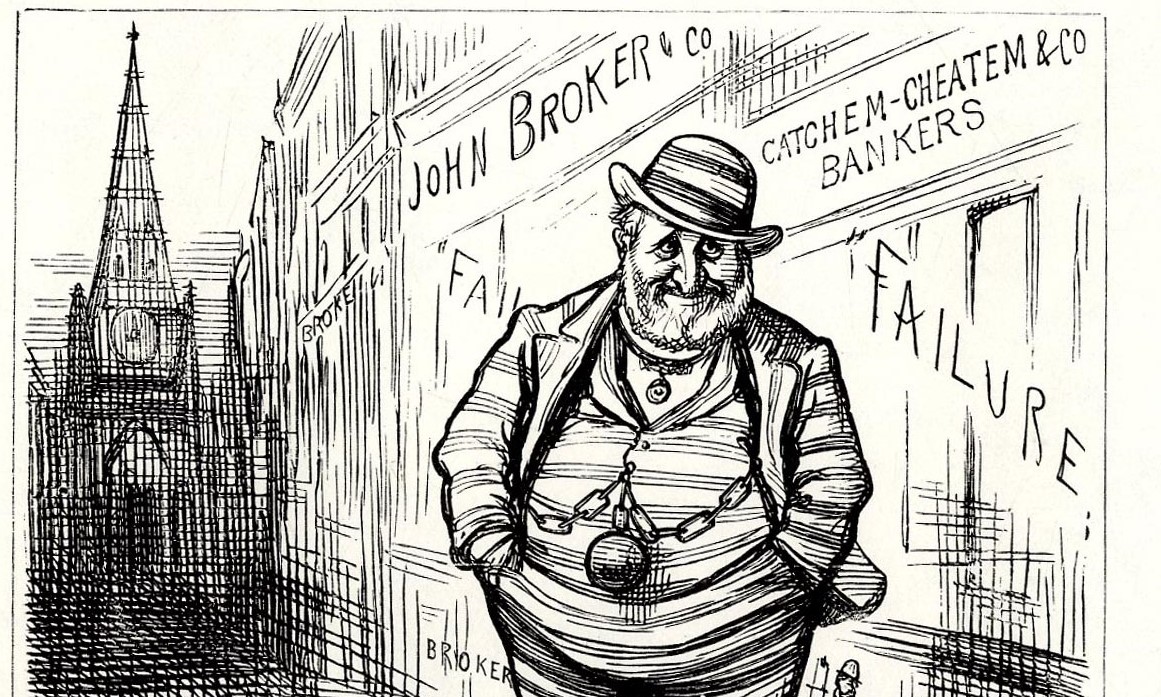

Harper's Weekly cartoonist Thomas Nast drew his famous cartoons, which are now among the classics of American political history, and pointed out whose pockets the money was going into. The genie was out of the lamp.

Months of persistent publications by NYT and Nast's cartoons finally yielded results and an investigation committee was established about Tweed. Law came into play. Tweed was arrested in October of the same year but was quickly released on bail with the bribes he paid.

He first went to Cuba and then to Spain. However, Nast's cartoons did not leave him there either. He was caught in Spain upon the notice of someone who recognized him from Nast's cartoons and was sent to the USA. While in prison, he agreed to share all the secrets and information of the Tweed gang with the New York state government in exchange for his release. He gave the information to the authorities, which is the source of much of the information in this article. However, he died of pneumonia in prison in 1878 before he could be released.